How Solar Energy Could Transform Geopolitics

November 21, 2025

How Solar Energy Could Transform Geopolitics

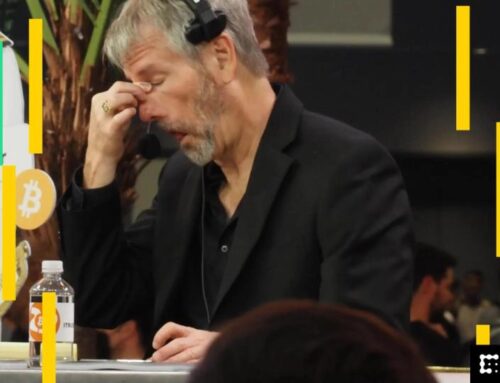

Environmentalist Bill McKibben on the incredible growth of clean energy in 2025.

In the month of May this year, China created more new wind and solar capacity than the electricity, from all sources, that Poland installed in the entirety of 2024. While part of the outlandishness of this statistic is because of companies racing to take advantage of expiring subsidies, it shouldn’t obscure the bigger picture that the sheer scale of Chinese industrial policy has made the mass global proliferation of clean energy a very real possibility. Could it eventually save the planet?

On the latest episode of FP Live, I spoke with the longtime journalist and environmentalist Bill McKibben, whose 1989 book The End of Nature is widely seen as one of the first to bring the idea of climate change into public consciousness. His latest book, Here Comes the Sun, is altogether more hopeful, exploring how solar energy is already transforming energy markets.

In the month of May this year, China created more new wind and solar capacity than the electricity, from all sources, that Poland installed in the entirety of 2024. While part of the outlandishness of this statistic is because of companies racing to take advantage of expiring subsidies, it shouldn’t obscure the bigger picture that the sheer scale of Chinese industrial policy has made the mass global proliferation of clean energy a very real possibility. Could it eventually save the planet?

On the latest episode of FP Live, I spoke with the longtime journalist and environmentalist Bill McKibben, whose 1989 book The End of Nature is widely seen as one of the first to bring the idea of climate change into public consciousness. His latest book, Here Comes the Sun, is altogether more hopeful, exploring how solar energy is already transforming energy markets.

Subscribers can watch our full conversation in the video box atop this page or follow the FP Live podcast for free. What follows here is a lightly edited transcript of our conversation.

Ravi Agrawal: You’re usually telling us how bad things are going to get. And here you are now focused on hope. Why?

Bill McKibben: Well, things are already bad. We’ve raised the temperature of the Earth by 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit). We’re seeing catastrophic results. The hurricane that hit Jamaica a few weeks ago featured the highest winds ever recorded, at 252 miles an hour. That same day, we had possibly the biggest rainstorm ever measured: 5 feet of rain in 24 hours in central Vietnam, the kind of storm you can only get on a globally warmed planet.

So the things that scientists have been worrying about for 40 years are coming true.

But we finally have a scalable and affordable weapon to go after some of this. Energy from the sun and wind, what we used to call alternative energy, is now the straightforward path ahead. Ninety percent of new electric generation around the world last year came from sun and wind and batteries.

This isn’t “alternative” anymore. It’s the most obvious way to proceed. Four or five years ago, we crossed an invisible line; it became cheaper to produce power from the sun and the wind than from burning coal and gas and oil. We live on a planet where the cheapest way to make power is to point a sheet of glass at the sun. That’s a pretty remarkable moment for a species that’s spent the last 700,000 years making its way by setting stuff on fire.

RA: Right now, most energy is generated from fossil fuels. Nuclear energy is probably about 10 percent of the total pie. Solar is still in the single digits in percentage terms, but its growth rate is the fastest. It has a long way to go, right?

BM: This autumn, the planet is generating a third more power from the sun than we were last autumn. The hope is that if we can keep that kind of growth rate up for a little while, then we’ll move into territory that makes a significant difference.

Sadly, it’s not the territory where we stop global warming. It is too late for that. But potentially the territory where we start shaving tenths of a degree off how hot the planet gets. Every tenth of a degree moves about 100 million people out of a safe climate zone and into a dangerous one. This is the most important work that anyone could be doing at this point.

RA: This May, China created enough new solar and wind to generate more energy than what Poland installed across all sources in a year. From January to May, China installed enough renewable infrastructure to generate as much energy as the country of Indonesia, the fourth-most populous country in the world, produces. Is this really a China story, or is it much more global than that?

BM: China’s definitely at the heart of it. The Chinese have made a full-scale economic bet that this is the future, and they are running with it. There’s no sign that they’re going to slow down anytime soon. They’re about to ratify their next five-year plan, and it calls for more sun, more wind, and especially more batteries, which take power from the sun and the wind and make it even more useful.

Just to give people a sense of how fast it can happen, in May, China was putting up about 3 gigawatts of solar power a day. One gigawatt is roughly equivalent to one coal-fired power plant. They were building one of those every eight hours with solar panels. This is energy that can be deployed with extraordinary rapidity.

But it’s not only a China story. We can talk about places all over the world, including in the developing world. Pakistan is seeing an explosion of solar energy—not as a result of a government program but as a result of individual Pakistanis who are fed up with the expensive and unreliable electric grid. They’re buying cheap solar panels from China, going on YouTube, and figuring out how to snap them together. The numbers there are astonishing.

It’s also happening in the developed world. Maybe the most remarkable story of the whole year happened a couple of weeks ago in Australia, where there are big solar farms and almost 40 percent of the homes have solar panels on the roof. The government announced that they have so much solar energy that beginning in January, Australians will get three free hours of electricity every day, even if they don’t have a solar panel on their roof.

You can schedule your dishwasher or your washing machine to run then. You could use those hours to charge up your electric vehicle. If you have a storage battery, which are now cheap, you can fill it up for free and run your household all night off that energy.

I say this just to bring home the really remarkable moment this is. Energy is often the biggest expense for many households. All of a sudden, in Australia, energy is going to be available free to everybody. That’s a promise for what’s possible around the world if we set our minds to it. That’s the kind of thing that will concentrate the minds of politicians.

RA: But there are so many things that muddy the waters. There is political opposition to clean energy, particularly solar. If you look at the history of energy, so much of it has been about being in the right place. Geography used to matter. Solar obviously just blows that up because you can be anywhere and access it. And that obviously means a lot of power shifts in the coming years.

BM: We’re just barely beginning to comprehend it. Think about what the geopolitics of our planet would have looked like over the last 100 years if oil had been of relatively trivial value. Think of the wars and coups and assassination attempts and terrorist plots that would have been avoided if the world was running on power sources available everywhere.

It’s a remarkable shift to go from a commodity that can be hoarded and stored and that produces extraordinary wealth for a relatively tiny coterie of people to an energy system that runs on something that happens every day, every place. We’re starting to see people and countries recognize that.

The Trump administration has been centering much of its foreign policy around what it calls “energy dominance.” It’s the idea that the future is going to be people buying American oil and liquefied natural gas (LNG), and that’s going to redound to our advantage. They seem to have been using tariff policy as a kind of coercive tool to get people on board with this agenda. If you pledge to buy enough LNG, then your tariff goes from 40 percent to 20 percent, or whatever the numbers are this hour.

That might work in the very short run. But I think most countries are starting to figure out that they’d much rather spend some money on Chinese solar panels and then depend on no one except the sun, which heretofore has risen most mornings across this planet.

The shift here is remarkable, and the impact will be most remarkable in the poorest countries. It’s worth remembering that nearly 80 percent of humans live in countries that have to import fossil fuel. You have to somehow come up with U.S. dollars to pay for the next shipload of oil waiting out in the harbor if you want to keep the economy going. In the not-too-distant future, that won’t be the reality anymore. It’s one of the pleasant ironies of the world that solar energy works better when you get toward the equator. Happily, wind energy works better toward the poles, which balances this out at some level. But the point is, this is stuff that’s available to everyone.

It’s not the world we’re used to, where Russia, Saudi Arabia, and China produce the bulk of the world’s energy supplies and—as a result—have immense geopolitical power. That world, all of a sudden, is shifting.

You can see that shift really starting to happen in Belém, Brazil right now, at COP30 (the U.N. climate conference). The United States, which has put far more carbon into the atmosphere than any other country, is the one country in the world not participating in those talks. We’ve decided we’re going to play no role in the climate solution.

That has let China fill the political vacuum. It’s already assuming technological and economic primacy. China has made significantly more money exporting green tech over the last 18 months than the U.S. has made exporting oil and gas over the same time. There’s no other number that so clearly demonstrates the shift.

RA: The country that has had arguably the greatest foreign-policy turnaround with the United States is Pakistan. And yet, Pakistan is also hedging its bets and is one of the greatest beneficiaries of solar energy because of its deep friendship with China.

I say all of this to underscore how we’re entering a world that is more transactional, but in which China’s appeal only grows as a purveyor of clean energy. Even in Belém right now, the official car for the COP conference is a Chinese electric vehicle.

With all of that said, I want to push back on the good news story here. How concerned are you about surveillance systems embedded in Chinese hardware, in panels, in grid infrastructure? American officials say that there’s a significant cybersecurity risk here that the likes of Pakistan and Brazil are not paying enough attention to.

BM: Look, I’m well aware that if I had spent my life in China doing what I’ve spent it doing in the United States—i.e., working hard to change government policies, sometimes by being out in the streets—I would have spent my life in jail. I have no particular affection for the Chinese government, which is one of the reasons it’s so sad that we’re ceding our primacy to them. When world historians write about the last nine months, they’ll describe the voluntary self-surrender of global leadership from the United States to China.

I don’t know if China is putting something in the solar panels it’s selling to Pakistan that allows it to spy on Pakistanis or turn off the power. I kind of doubt it. Now, this is pretty straightforward technology occurring at a volume that we’ve never seen before. It’s not solar panels, by the way; it’s the stuff that makes use of all that energy. If anyone still thinks that Detroit is the center of the world’s automotive industry, they’ve got another thing coming. There are two or three cities in China producing the best and cheapest cars on planet Earth. They’re already dominating the export market in the developing world. They’d be dominating our automobile market, too, if we didn’t tariff them out of existence in America.

So we better come up with a more convincing argument than that. If we’re serious about slowing China down, we need to do what [former U.S. President Joe] Biden tried to do with the Inflation Reduction Act, which devoted significant resources to trying to compete with China in the industries of the future. Instead, we’ve decided that it would be smart to try to wring the last dollars out of 18th-century technology.

RA: I’ll point out, Bill, that Biden was trying to do both things: He was trying to win the future but also biding time. One of my critiques of the Biden administration was that if they truly wanted to have EVs dominating internal combustion engine cars, it was very easy: China was doing it for them. They just didn’t allow it to happen.

BM: Biden could have used a couple more votes in the U.S. Senate to play with. I think he did about as well as he could have, given his political power. But yes, the writing is on the wall. This is the way to become a part of the future—not to control the future in quite the same way that energy supplies have controlled the past.

China’s selling the tech, but China doesn’t own the sun. That makes for a very different world. I think we’re going to have a much more multipolar world—a world where dominance is going to be much less of a theme than it’s been in the past, at least in energy.

That’s a good thing on many counts. If you asked me what the two biggest crises on the planet right now are, one of them is climate and the other is authoritarianism. This takes some bite out of both, with the caveat that China is a very authoritarian place, and it’s playing a pivotal role.

RA: Another critique of this idea that solar and clean energy can fix many of the world’s crises is that clean energy still has a dirty element to it. There’s a very high original carbon load to build batteries and solar panels. You need all kinds of critical minerals and rare earths, which as we know, entail a lot of competition, dirty mining, and processing that have all kinds of adverse impacts on the planet. How do you game that out?

BM: Mining almost always is a scourge on the places where it happens and the people who have to do it. The good news is that the energy transition will end up using a lot less mining. You mine some lithium, which we should do as environmentally soundly and humanely as we can, and once you’ve done it, you stick it in a battery, and it does its lithium thing for a quarter-century until the battery degrades. We know how to recycle it, get it out, and start over again.

If we somehow run short on lithium, the Chinese are now producing cars that run on sodium ion batteries. Sodium is the one of the most common elements in the world’s crust. If you mine coal, you set it on fire, and then you have to mine more the next day. It’s a very different mindset.

The Rocky Mountain Institute estimates that the total mining burden for the renewable battery revolution by mid-century will be less than the amount of coal that we mined last year on this planet. Another way to think about it is that a shipload of solar panels will produce about a hundred times as much energy as a boatload of coal over its lifetime. It’s not just a different commodity. It’s a different paradigm.

We’re combining some fairly small amounts of minerals with a lot of human ingenuity, and we get better at it all the time. I put solar panels all over my roof 25 years ago. They’re still working fine, but at a certain point, the panels will begin to degrade. When they do, the minerals in those solar panels—some silver, some boron—get recycled. One panel from 25 years ago has enough of that stuff in it to produce six 2025 panels.

RA: As we think about China having such an edge on solar and wind, it also has a huge edge on rare-earth minerals. Part of that is supply chains, but the much bigger part is processing, which is much harder to catch up on for all kinds of environmental reasons. China controls 92 percent of that market.

BM: China figured out early that this was the future and ran with it. For the many sage critiques one can make of Beijing, there’s also the fact that in this realm, they’ve behaved more responsibly than the West has. They figured out we needed this, partially because China was such an environmental basket case.

Ten or 15 years ago the list of the most polluted cities on earth was all Chinese. None of those cities make that list anymore. I haven’t been to China in the last year or two, but I’ve talked to friends who say that if you stand on the street corner in Beijing or Shanghai, it’s not only much cleaner, but it’s also way quieter than it was because most of the cars going by are electric.

RA: I was there this summer, and I can vouch for that. But China still does open a lot of new coal plants, although the utilization of them is low, in the 50 percent range. Is that right?

BM: China is using them as a kind of backup power because they’re more expensive to run than the solar and wind installations. One suspects that will tail off, especially as we get better at utilizing batteries. The cost of batteries is coming down extraordinarily. The Chinese tenders for big battery construction this year are as much as 30 percent below the price they were a year ago. That’s the next part of this revolution. It appears that Chinese carbon emissions may have peaked this year.

RA: There’s some data suggesting it’s down by 1 percent, but it’s a bit murky.

BM: It’s a bit murky, and we may bounce around the top of this plateau for a little while. But American carbon emissions definitely went up this year. You’re seeing a split here, and I think we made the wrong bet. Our bet seems to be on artificial intelligence (AI) as the future.

RA: I was just going to bring that up, Bill, because it’s impossible to have a discussion these days without AI coming up as a big component. Do you see AI as the thing that is going to need so much more new energy that it will lead to “drill, baby, drill”? Or is it going to accelerate investments in solar and even nuclear?

BM: That’s exactly the right question. One way to look at the AI build-out is that it’s being used by the Trump administration and the oil and gas industry as one more justification for one more round of gas-fired power. But in a rational world, we’d be using it just as the opposite—as the leverage to very rapidly build out clean energy.

I’m agnostic on whether we really need to be building 8 zillion data centers everywhere. If you decide that we do, that we’re in some race with the Chinese, that it’s desperately important that we win, the only way to build it fast is to build with sun and wind.

The United States is in this very strange posture right now. On day one of the new administration, we declared an energy emergency on the grounds that we needed lots of energy to power AI to keep up with China. Then we decided that we were not going to build any of the cheapest forms of energy. We shut down construction on wind farms that are 80 percent complete off the coast of New England. A few weeks ago, we shut down work on what would have been the biggest solar farm in the country, in Nevada, which would have powered 2 million homes. We’re simultaneously increasing demand and constricting supply. The cost of electricity is therefore going through the roof for Americans.

My guess is that the price of electricity is going to be a big part of the midterm elections. The Democrats better get good at explaining what I just explained, that for some reason, we’ve decided not to use the most available and affordable source of energy.

RA: One thing I often hear is that solar and wind are intermittent sources, and therefore not very reliable—certainly not enough for data centers. How do you refute that?

BM: This is why we have batteries. It’s not like this is like some bizarre concept of batteries. We all understand that’s why you can carry around your laptop and use it whenever you want. At night now in California, often the biggest source of supply to the grid is batteries that spent the afternoon soaking up excess sunshine. Those batteries didn’t exist three years ago.

They also exist at all kinds of other scales. Where I live in Vermont, our biggest power plant is what they call a virtual power plant. It’s around 7,000 batteries in people’s basements that our utility company helped people buy. The batteries can be knit together on days of peak power demand and be used as supply. These virtual power plants are now being built out on a large scale elsewhere. The biggest one soon will be in Texas, which—by the way—is building more clean energy than any state in the union.

This revolution is happening at many scales. Very large, like those vast power plants you see covering the tops of mountains in China, and very small. In Europe, we’ve seen an explosion in what’s called balcony solar in the past few years. People go to the local Best Buy—or whatever you call it in Milan—and come home with a panel designed to hang over the railing of the balcony. There’s a standard plug on the back, you stick it in the wall, and then you’re often supplying 20 percent to 25 percent of the power an apartment uses. That’s currently illegal everywhere in the United States except Utah.

RA: Bill, let’s end where we began. You picked a Beatles song for the title of your book, and you have a very reassuring quote from George Harrison on Page 1: “And I say, it’s all right.” Why did you go that route?

BM: Aside from the practical necessity of this energy revolution, there’s also something beautiful about it. When you go to Spotify, it turns out that “Here Comes the Sun” is the most listened to song in the Beatles’ vast catalog, partly because it’s a beautiful and optimistic song in a dark time, but also because humans have a deep connection to the sun. There are hundreds and hundreds of songs about the sun—somewhat more than the list of good songs about fracking, it must be said. It turns out that people across the ideological spectrum are eager to see way more development of sun and wind. This is human scale technology.

I was in the Vatican in September, when Pope Leo XIV made it clear he’s going to follow Pope Francis’s lead on making climate change a priority. The Vatican will become the first fully solar powered nation on Earth sometime next year. They flipped the switch on a solar farm they’ve been building outside Rome.

So I said, “I think this is fantastic. It gives us the mantra for the future: Energy from heaven, not from hell.” That’s the organizing principle for the planet going forward, and my only hope is that we didn’t wait too long. If it takes us 30 years to run the planet on sun and wind because it’s cheap, it’ll be a broken planet that we run on sun and wind because climate change is now happening in real time.

Our job is to speed up this transition as best we can in hopes of heading off as much damage as is still possible. Let’s hope we can.

Ravi Agrawal is the editor in chief of Foreign Policy. X: @RaviReports

Stories Readers Liked

The Scramble for Critical Minerals

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post