Investing in an emerging supplier to encourage product innovation under market competition

April 5, 2025

Abstract

With the intensification of economic globalization and market competition, manufacturers collaborate with upstream enterprises to build a supply chain with close technical relationships. However, the technology spillover effects caused by direct investment in established suppliers often lead to competitors free-riding, thereby weakening the incentive for enterprises to invest. Consequently, more and more manufacturers tend to invest in emerging suppliers to prevent technology spillovers while also triggering competition among suppliers to gain procurement and competitive advantages. This study explores how a manufacturer chooses the optimal investment strategy to develop an emerging supplier in the face of varying market competition intensities and R&D uncertainty. The research considers three investment strategies: equity investment, loan investment, and cost-sharing, and analyzes the implementation effects of these strategies. We find that in highly competitive markets, the manufacturer tends to choose loan investment to reduce risk; interestingly, in moderately competitive markets, the manufacturer opts for equity investment when the shareholding ratio is small; and in less competitive markets, the manufacturer prefers equity investment when the shareholding ratio is large. Additionally, an increase in the probability of R&D success may make the manufacturer more inclined to adopt loan investment. From the perspective of product innovation, both equity investment and cost-sharing are more effective in motivating the emerging supplier to engage in product innovation, primarily depending on the depth of the manufacturer’s equity. However, an increase in the probability of R&D success tends to inhibit such innovative activities. Importantly, we also find that the manufacturer chooses not to invest in the emerging supplier when the competition intensity exceeds a certain threshold. This highlights the critical role of competition intensity in driving enterprises’ investment decisions. These findings can provide valuable managerial insights for the innovative development of supply chains.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

At present, changing customer demands and fierce market competition have prompted manufacturers to accelerate technology iteration and product innovation, and the risk of supply disruption caused by various external shocks and the upgraded demand for core parts of the manufacturing industry have made many manufacturers begin to strengthen cooperation with upstream suppliers to jointly develop more competitive innovative products (Zhang et al. 2024). However, it is often the case that upstream suppliers supply raw materials or components to multiple downstream manufacturers at the same time, and when one downstream manufacturer directly invests in upgrading the upstream supplier, there may be a technology spillover effect to the benefit of other horizontally competing manufacturers (Agrawal et al. 2016; Niu and Shen 2022). For example, Apple has promoted the development of glass technology by investing in its screen supplier, Corning Company, which is not only used in Apple products but also in Samsung and Huawei products by Corning Company (Expreview 2021). Spillover effects can cause competitors to free-ride on shared suppliers without bearing any investment costs, thereby reducing the incentive for manufacturers to invest in these suppliers (Xia et al. 2023). To this end, some manufacturers have begun to choose to invest in emerging suppliers. On the one hand, it can effectively prevent technology spillover and trigger competition between suppliers, thus obtaining procurement advantages (Li and Wan 2017). On the other hand, new products are often supplied by innovative and flexible emerging suppliers, with whom a greater competitive advantage can be gained through cooperation in successful R&D (Zhang and Lee 2022).

To develop these emerging suppliers, manufacturers typically invest in them in a variety of ways. Among them, equity investment, loan investment, and cost-sharing are the three most common and effective strategies. In equity investment, manufacturers receive a stake in emerging suppliers, whose return on investment will be affected by the results of R&D (Qian et al. 2024). For example, Intel Corporation, to gain a larger market share in the competition with TSMC, while using the existing wafer and lithography technology at the time, also spent $4.1 billion to acquire a 15% equity stake in ASML to accelerate the development of two new technologies in ASML (Zhang and Lee 2022). In loan investment, manufacturers directly provide R&D funds for emerging suppliers to help them develop new products, but they will not share benefits and risks with them and will recover the principal and interest at maturity (Gao et al. 2024). One of the most typical examples is that to ensure its competitive advantage in the high-end mobile phone market and obtain the exclusive right to use the advanced sapphire screen, Apple signed a $589 million loan contract with GTAT to accelerate the development of GTAT’s advanced sapphire screen (ithome 2014). Under cost sharing, manufacturers will partner with emerging suppliers to share a percentage of their R&D costs (Ding and Jian 2024). For example, while Panasonic has already provided mature lithium-ion battery technology to the market, Hyundai Motor will still choose to cooperate with IONQ, an emerging quantum computing company, to share R&D and application costs to optimize the development process of battery materials (Chinese Academy of Sciences 2022). Different investment strategies provide different incentives for manufacturers and suppliers and have different potential impacts on risk allocation, profit sharing, and cost-sharing. At present, it is not clear which investment strategy manufacturers choose is the best, especially in the fierce market competition environment.

Furthermore, when emerging suppliers invest in R&D, there is a certain probability that product innovation will not be achieved, meaning that the outcome of R&D is not always successful. This uncertainty also becomes an obstacle for manufacturers to invest in emerging suppliers, as they can lead to significant sunk costs (Niu and Shen 2022). A very typical example is the case of Apple’s investment in GTAT. Despite Apple’s $589 million loan investment to accelerate R&D, the production of sapphire screens faced numerous challenges, including strict environmental requirements, uncontrollability of the production process, and uncertainties in the time and cost of cutting large crystals, which ultimately led to the failure of the R&D and GTAT’s bankruptcy. Apple then reverted to its original screen supplier, Corning. Therefore, it is crucial to consider the uncertainty of R&D when exploring manufacturers’ supplier development strategies. Consistent with the research of some scholars (Zhang and Lee 2022; Zhang et al. 2024), we also model the uncertainty of innovation outcomes as the probability of R&D success, focusing on how this uncertainty affects investment decisions.

At the same time, from an innovation perspective, the three cases also raise another important question for manufacturers before making investment choices: Which investment strategy can more effectively incentivize emerging suppliers to engage in product innovation? As is well known, under equity investment, there is profit sharing between manufacturers and suppliers, so manufacturers may offer higher procurement prices, thereby incentivizing emerging suppliers to develop products. However, it is precisely this profit-sharing effect that may weaken suppliers’ motivation for continuous innovation (Haw et al. 2023; Chen 2024). Under loan investment, due to limited liability in the event of failure, non-labor costs (e.g., equipment, facilities, etc.) will not be internalized. This means that if the R&D fails, suppliers do not have to bear the entire non-labor cost investment. This limited liability protection reduces the potential losses for suppliers in the event of failure, thereby potentially encouraging them to make greater investments in R&D (Zhang and Lee 2022). On the other hand, under loan investment, manufacturers do not share profits or risks with them. At this time, emerging suppliers not only face the risk of product development failure but also bear the pressure of repaying loans, which may lead to adopting conservative strategies and reducing product innovation (Dong et al. 2023). Unlike the previous two strategies, under cost-sharing, manufacturers and suppliers jointly bear R&D costs and share risks. In this strategy, emerging suppliers do not need to share profits with manufacturers, nor do they face the pressure of repaying loans, which may allow them to focus more on technological innovation. Thus, it is evident that regardless of the investment strategy adopted by manufacturers, the impact on product innovation by emerging suppliers is complex. It is unclear which specific strategy can incentivize emerging suppliers to engage in greater product innovation, and this is precisely what is lacking in current research. Based on the above background and facts, this paper aims to address the following questions:

-

(1)

What is the optimal investment strategy for the manufacturer? What are the other members’ strategy preferences for the manufacturer?

-

(2)

When there is R&D uncertainty, what investment strategies can incentivize the emerging supplier to carry out greater product innovation?

-

(3)

How do key factors such as market competition intensity and R&D probability affect the pricing and strategy choices of supply chain members?

Thus, we consider a high-tech supply chain in which an established supplier supplies a key component to both the manufacturer and its competitor. To cope with the fierce market competition and the rapid update and iteration of technology, the manufacturer will collaborate with the emerging supplier to develop more advanced and competitive products, but there is uncertainty in the innovation of new products. If the product is successfully developed, the manufacturer will source parts from the emerging supplier; otherwise, it will still source from the established supplier. In this context, we construct three-game models of manufacturers’ investment strategies: equity investment, loan investment, and cost-sharing. Then the influence of market competition intensity and R&D uncertainty on supplier development strategy is studied. Finally, as extensions, we also explore the non-negative effects of improving innovative R&D capabilities and production costs, and we confirm that the main findings are still valid and the model is robust.

The main findings are as follows: first, the manufacturer’s investment strategies for the emerging supplier are significantly different under different competitive intensities. In the fierce market competition, the manufacturer is more inclined to choose the loan investment strategy to reduce the risk of R&D failure; when the competition intensity is moderate, the manufacturer will choose the equity investment strategy if the shareholding ratio is small. Interestingly, in the environment of weak market competition, the manufacturer is more inclined to choose equity investment when the shareholding ratio is large. In addition, the increased probability of R&D success may make the manufacturer more inclined to take on loan investment. Second, when there is R&D uncertainty, equity investment, and cost-sharing strategies are generally more effective in incentivizing the emerging supplier to undertake greater product innovation, depending on the depth of the manufacturer’s shareholding. In contrast, while loan investment can somewhat aid in R&D, the pressure on the supplier to repay the loan and bear the risk of R&D failure alone may lead to adopting more conservative strategies, thereby limiting product innovation. Third, while competition generally incentivizes the manufacturer to develop an alternative supply chain, there exists a critical threshold where, when the competition intensity is less than this threshold, the manufacturer may opt not to invest. This result forms an important contrast with the general view that competition stimulates innovation in the current literature.

The structure of the next parts is as follows: The second part is to review the relevant literature. The third part describes the model and assumptions. The fourth part is the solution and analysis of the three models. The fifth part is an extension, which further tests the robustness of our conclusion. The sixth part summarizes the full text and puts forward the corresponding suggestions. The seventh part describes the limitations and prospects of this study.

Literature review

The literature closely related to this study mainly focuses on the following two aspects: one is supplier development, and the other is the choice of investment strategy. Next, we will sort out and summarize the existing research from the above two aspects.

As for supplier development, scholars define it as all actions taken by upstream and downstream enterprises to improve supply chain performance or meet the needs of downstream enterprises for business and strategic development (Prahinski and Benton 2004). As a popular method to mitigate supply risks, supplier development has received extensive attention in both production practice and academia. Xie et al. (2024), Porteous et al. (2015), Chen (2024), and Yu et al. (2022) and other scholars respectively discussed how the manufacturer can improve their financial performance, reduce environmental violations, and improve innovation management ability through supplier development. A reasonable supplier development strategy is not only conducive to product development and innovation but also can improve the market competitiveness of enterprises. However, most of these studies focus on the impact of supplier development on internal corporate performance, with less attention paid to its strategic significance in a competitive market environment. When enterprises invest in shared suppliers, it may generate technology spillover effects, benefiting other horizontally competing manufacturers (Agrawal et al. 2016). For example, in the face of potential competitor intrusion, Liu et al. (2023) studied the upstream technology investment strategy under technology spillover. It turns out that investment in technology backfires on competitors. Xia et al. (2023) studied the environmental quality investment of two competing vendors in a shared supplier and found that technology spillover would make the manufacturer affected by the competitor’s investment. As a result, some students have begun to discuss investment decisions with specific suppliers. When the investment of the manufacturer can reduce the production cost but there is uncertainty, Zhang et al. (2024) discussed whether the manufacturer should invest in one or two suppliers. The research shows that when the development ability of the manufacturer is weak, the two suppliers should be invested; Moreover, when the chances of success of investing in one or two suppliers are equal, the investment capacity of the manufacturer can be improved. Hu and Tadikamalla (2023) mainly study how to introduce sub-suppliers to improve the innovation quality of production when there are already main suppliers. Veldman et al. (2023) focused on the problem of shared or vendor-specific development, finding that investing only in a specific vendor leads to a prisoner’s dilemma for the buyer, and further emphasizing that competitors free ride on the buyer’s technology investment. Clearly, existing literature primarily discusses the investment decision-making problem of manufacturers in developing emerging suppliers in the presence of established suppliers, but the research focus is more on “who to invest in,� that is, whether to invest in established suppliers or emerging suppliers. This study, however, aims to address the question of “how to invest,� that is, what strategies the manufacturer should adopt to most effectively invest in the emerging supplier. Moreover, from the perspective of supplier entry, a significant amount of literature has overlooked the critical factor of downstream competition, which is often one of the motivations driving enterprises to invest upstream. This paper constructs a game-theoretic model to systematically analyze the impact of market competition and R&D uncertainty on the manufacturer’s investment strategies, filling the gap in existing research.

In terms of investment strategy selection of downstream enterprises, most literature focuses on financial support (Tang et al. 2018), equity investment (Xiao et al. 2021), process improvement (Niu and Shen 2022), and cooperative development (Yu et al. 2022). Among them, equity investment, loan investment, and cost-sharing are most relevant to our research content, so we will focus on these three investment decisions next. As an important way to achieve deep internal cooperation in the supply chain, equity investment has gradually become a hot topic discussed by scholars, and most studies focus on the change in enterprise operation decisions and performance under vertical shareholding (He et al. 2022). Xia et al. (2023) studied the impact of backward shareholding on supply chain members under information symmetry and asymmetry and found that backward shareholding is always beneficial to upstream enterprises, while downstream enterprises can obtain higher profits only when certain conditions are met. Loan investment is also one of the effective ways for enterprises to develop emerging suppliers. Most scholars focus on the financing behaviors of upstream and downstream enterprises and pay attention to supply chain pricing, ordering, coordination, and other decisions under different financing scenarios (Jin et al. 2019). Hovelaque et al. (2022) demonstrated that cash holdings and discount rates of downstream enterprises would have a certain impact on their borrowing methods. In the case of supply chain cooperation, cost-sharing contracts have been widely applied in theory and practice (Ding and Jian 2024). From the perspective of supply chain efficiency, cost sharing is conducive to reducing the risk of supply chain cooperative members, alleviating the double marginal effect of the supply chain, and improving system efficiency (He, et al. 2019; Zhang, et al. 2023). In addition, some scholars have discussed and compared the investment strategies within the supply chain. Lin and Xu (2024) studied how pricing license contracts and production license contracts incentivize suppliers to reduce product defect rates, and further compared the performance of the two types of contracts. Zhang and Lee (2022) compared the investment decisions of high-tech manufacturers in immature new technology suppliers under equity investment and loan investment. To help suppliers overcome financial difficulties, Xie et al. (2024) compared the two strategies of direct financing or guaranteed financing and found that downstream enterprises are always more inclined to choose guaranteed financing when their loss aversion level is large. Ren et al. (2021) compared different shareholding strategies and found that cross-shareholding is the optimal strategy when both current and backward shareholding rates are low, and both upstream and downstream members can improve profits through supply chain coordination. Unlike most studies that focus on a single investment strategy, this paper not only systematically compares three different investment strategies—equity investment, loan investment, and cost-sharing—but also explores the impact of different investment strategies on the product innovation of the emerging supplier. Furthermore, this paper also considers the impact of market competition intensity on strategy selection, finding significant differences in the manufacturer’s investment strategies towards the emerging supplier under varying competition intensities. This paper provides a new perspective on understanding how market competition and R&D uncertainty jointly influence the manufacturer’s investment strategy choices, and it also serves as a supplement to emerging supply chain management practices.

In summary, this paper makes significant contributions and innovations to the existing literature in the following three aspects: first, it focuses on how the manufacturer chooses investment strategies for the emerging supplier in the context of market competition and R&D uncertainty. At the same time, we delve into the impact of different investment strategies on the product innovation incentives of the emerging supplier, an issue that has not been sufficiently addressed in the existing research. Although existing research has addressed the role of supplier development in enhancing corporate performance, it often overlooks the complex impact of market competition and R&D uncertainty on investment strategy choices, as well as how these strategies incentivize the supplier to engage in greater innovation. Secondly, like the study by Zhang et al. (2024), this paper also explores the issue of how the manufacturer can develop the emerging supplier in the presence of the established supplier in the market. However, our research focuses on “how to invest,� that is, what strategies the manufacturer should adopt to effectively invest in the emerging supplier. In contrast, Zhang et al. (2024) focus more on the question of “who to invest in,� that is, whether the manufacturer should choose to invest in a single supplier or multiple suppliers, without delving into the specific implementation methods and effects of different investment strategies. Finally, this paper systematically compares three different investment decisions: equity investment, loan investment, and cost-sharing, and particularly considers the impact of market competition intensity on strategy choices. Unlike the study by Zhang and Lee (2022), which primarily compared equity investment and loan investment strategies, this paper not only covers more investment strategies but also delves into how market competition intensity affects the manufacturer’s choices between different strategies. The research results indicate that the manufacturer exhibits significant differences in its investment strategies towards the emerging supplier under varying levels of competition. This finding provides a new perspective on understanding the impact of market competition on investment decisions and offers important reference points for the manufacturer’s strategic choices in complex market environments. We have summarized the comparison of this paper with the most relevant literature in Table 1 to further highlight the unique contributions and innovations of this study.

Model setup

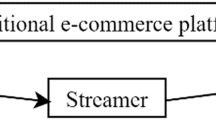

In a high-tech supply chain, an established supplier (o) supplies a key component to the manufacturer (m), and the manufacturer (c), competes horizontally. To cope with the fierce market competition and the rapid update and iteration of technology, the manufacturer (m) may cooperate with the emerging supplier (n) to take equity investment, loan investment, or cost-sharing to develop more advanced and competitive products. However, the innovation of the new product usually implies uncertainty, assuming that (theta) is the probability of success of new product innovation, then (1-theta) indicates the likelihood of failure. If the product is successfully innovation, the manufacturer (m) will purchase the part from the emerging supplier (n), otherwise, it will still purchase from the established supplier (o). The model structure described above is shown in Fig. 1. Table 2 gives the definition and description of the relevant symbols.

There are three investment strategies for the manufacturer, which are defined as follows:

Equity investment strategy (EI)

In the equity investment strategy, the manufacturer receives a stake in the emerging supplier, and its return on investment will be affected by the results of R&D (Qian et al. 2024). If the product is successfully developed, the emerging supplier is required to share its enterprise value with the manufacturer in proportion to the manufacturer’s shareholding (kappa). Like Chang et al. (2023), to ensure that the emerging supplier always has the right to make independent decisions, the shareholding ratio of the manufacturer should not exceed 50%, that is, (0 < kappa < 1/2). For example, in 2012, Intel Corporation, to gain a larger market share in the competition with TSMC, while using existing wafer and lithography technology at the time, also spent $4.1 billion to buy a 15% stake in ASML. To accelerate the development of two new ASML technologies and commit to accepting advance purchase orders from ASML (Zhang and Lee 2022). In the field of new energy vehicles, although Xiaomi has adopted the ternary lithium battery of CATL, Xiaomi still invested 375 million yuan in Ganfeng Lithium Battery Company and held 7.01% of its equity to further consolidate its strategic layout in the power battery supply chain (36Kr 2021).

Loan investment strategy (LI)

Under the loan investment strategy, the manufacturer directly provides R&D funds for the emerging supplier to help it develop a new product, but the manufacturer will not share benefits and risks with the supplier and will recover the principal and interest at maturity (Gao et al. 2024). The loan interest rate made by the manufacturer to the emerging supplier is charged at (r). For example, Siemens has provided loan financing to Curetis AG to help it develop innovative molecular diagnostics (SIEMENS 2024). Other similar cases also exist in the mobile phone industry, Apple and Huawei two mobile phone manufacturers have purchased mobile phone screens from Corning at the same time, but to ensure their competitive advantage in the high-end mobile phone market, and obtain the exclusive right to use advanced sapphire screen, Apple signed a loan contract worth 589 million US dollars with GTAT. Designed to accelerate the development of GTAT’s advanced sapphire screen. In addition, the contract provides that if the production of sapphire screens does not meet Apple’s operational goals, the contract allows Apple to withdraw and reinstate its existing supplier: Corning (ithome 2014).

Cost-sharing strategy (CS)

Under the cost-sharing strategy, the manufacturer enters into an agreement with the emerging supplier to share the product innovation cost of (beta), and the emerging supplier bears the remaining (1-beta) (Ding and Jian 2024; Jiang et al. 2024). To avoid the manufacturer having too much influence on the emerging supplier’s R&D decisions, thus weakening the supplier’s independence and ability to innovate, (0 ,<, beta ,< ,1/2) is assumed. For example, while Panasonic has already provided mature lithium-ion battery technology to the market, Hyundai Motor will still choose to cooperate with IONQ, a new quantum computing enterprise, to share R&D and application costs to optimize the development process of battery materials (Chinese Academy of Sciences 2022). In addition, BMW has partnered with Solid Power to develop solid-state battery technology, and the two parties have jointly advanced the development and commercialization of this cutting-edge technology through cost sharing. BMW contributed a portion of the R&D costs and provided the necessary technical support and marketing resources for Solid Power (BMW GROUP 2023). Through a cost-sharing strategy, the manufacturer can maintain a competitive edge in emerging technologies, while the emerging supplier can gain stable financial support and valuable industry resources to further accelerate its technology development and marketing.

On the demand side, based on the Hotelling linear market model, this paper assumes that manufacturers (m) and (c) are located at 0 and 1 at the left and right ends of the market, respectively, and compete in product quality and price. Without loss of generality, we assume that there is a unique consumer, randomly and evenly distributed on a line, who buys a unit of product from either (m) or (c) (Lauga and Ofek 2016). Meanwhile, if the consumer is located at (x,(xin left[mathrm0,1right])), then the transportation cost of the consumer to the enterprise (m) is (tx), and the transportation cost of the consumer to the enterprise (c) is (t(1-x)) (Qi et al. 2016). If the product of R&D is successful, and the innovation degree of product of emerging supplier is (s) compared with that of the established supplier, the utility obtained by consumers buying products from manufacturers (m) and (c) are respectively: (U_Ym=v+s-tx_Y-p_m) and (U_Yc=v-t(1-x_Y)-p_c), consumers will choose products that maximize utility, so the product requirements of manufacturers (m) and (c) are: (left\beginarraycd_Ym^Z=fracp_c-p_m+s2t+frac12\d_Yc^Z,=frac12-fracp_c-p_m+s2tendarrayright.). If the emerging supplier’s product development fails or the manufacturer chooses not to invest in the emerging supplier, both manufacturers buy products from the established supplier, and they have the same consumption quality and only compete on price (Niu and Wang 2024). The utility obtained by consumers buying products from manufacturers (m) and (c) are respectively: (U_Nm=v-tx_N-p_m) and (U_Nc=v-t(1-x_N)-p_c), the product requirements of manufacturers (m) and (c) are: (left\beginarraycd_Nm^Z=fracp_c-p_m2t+frac12\d_Nc^Z,=frac12-fracp_c-p_m2tendarrayright.), consistent with de Bettignies et al. (2023) (2023), since unit transportation cost (t) also represents the degree of horizontal differentiation, its reciprocal (b=frac1t) can be used to measure the intensity of product market competition.

To focus on the analysis of the main impact, this paper does not consider other variable costs unrelated to product innovation, that is, assuming that the cost per unit of production of the product is 0, which is relaxed in the section “Impact of non-negative production costs�. Following Zhang et al. (2024) and Wei et al. (2024), we set the innovative R&D expenditure of the emerging supplier as (ks^2), where (k,(0 ,< ,kle 1)) representing the innovative development capability of the emerging supplier, and the smaller (k), the stronger the innovative R&D capability of products. To better reflect the research in the section “Enhance the impact of the innovative R&D capabilities� that product R&D capabilities of the emerging supplier can be enhanced under CS, we assume here that (k=1) (which is relaxed in the section “Enhance the impact of the innovative R&D capabilities�). Without affecting the main research conclusion, this formula can also capture the law of increasing cost margin more succinctly. Furthermore, consistent with the studies by Chang et al. (2023) and Guo et al. (2024), we assume (kappa), (r) and (beta) are exogenous. The assumption of the exogeneity of these parameters not only better reflects the impact of external conditions but also allows us to focus on analyzing how they influence the manufacturer’s investment decisions and emerging suppliers’ product innovation.

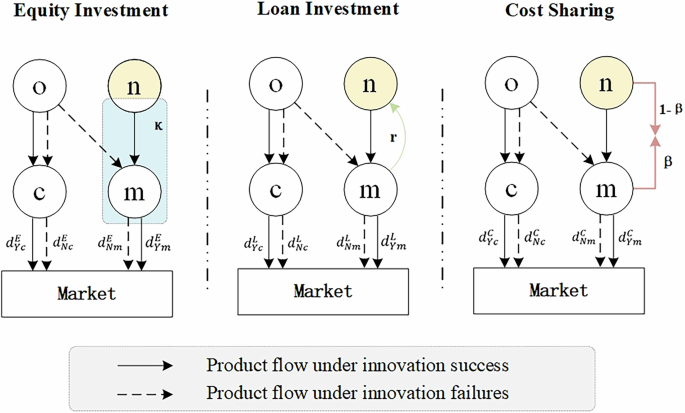

The sequence of events is shown in Fig. 2. In the first stage, the manufacturer decides whether to invest in the emerging supplier; in the second stage, if the manufacturer decides to invest in the emerging supplier, the manufacturer first chooses the cooperation strategy with the emerging supplier; then, the emerging supplier decides the degree of product improvement, and the suppliers decide the unit wholesale price for the downstream manufacturers, respectively; finally, the manufacturer and its competitor decide the retail price of the product, respectively. If the manufacturer decides not to invest in the emerging supplier, then the established supplier first determines the wholesale prices for downstream manufacturers, and then the manufacturer and its competitor decide the retail prices for the products, respectively.

Analysis

In this section, we first introduce the equilibrium results under different strategies. Then, we explore the conditions under which it is profitable for the manufacturer to invest in the emerging supplier. Based on this, we provide a sensitivity analysis and comparison of relevant parameters under different investment strategies when the manufacturer invests in the emerging supplier. Next, we discuss the strategy preferences of supply chain members under different investment strategies. Finally, we compare consumer surplus and social welfare under different investment strategies.

Equilibrium results

First, we consider the decision-making process of the manufacturer when choosing to invest in the emerging supplier. In Strategy Z, the emerging supplier first decides the extent of product improvement through R&D. At this point, the optimization problem under different investment strategies is:

Among them, (E[pi _n^Z]) represents the expected profit of the emerging supplier when the manufacturer chooses the Z strategy, while the first term on the right side of the equation represents the expected profit when the emerging supplier’s product development is successful, and the second term represents the product development expenditure of the emerging supplier.

Then, the emerging supplier and the established supplier simultaneously decide the wholesale prices for the given downstream manufacturers. At this point, the optimization problem under different investment strategies is:

Among them, (E[pi _o^Z]) represents the expected profit of the established supplier when the manufacturer chooses the Z strategy, while the first term on the right side of the equation represents the expected profit of the established supplier when the emerging supplier’s product development is successful, and the second term represents the expected profit of the established supplier when the emerging supplier’s product development fails.

Finally, the manufacturer and its competitors simultaneously decide the retail price of the product. At this point, the optimization problem under different investment strategies is:

Among them, (E[pi _m^Z]) and (E[pi _c^Z]) represent the expected profits of the manufacturer and its competitor, respectively. The first term on the right side of the equation represents the expected profit for the manufacturers when the emerging supplier’s product development is successful, the second term represents the expected profit for the manufacturers when the emerging supplier’s product development fails, and the third term represents the gains or expenditures when the manufacturer chooses different investment strategies.

When the manufacturer chooses not to invest in the emerging supplier, that is, in strategy N, the established supplier first decides the wholesale prices for downstream enterprises, and then the manufacturer and their competitor respectively decide the retail prices for the products. Since the profit function expressions for the game participants are relatively simple and can be given by the above equations, they will not be repeated.

Based on the above analysis, the equilibrium results and expected profits of upstream and downstream enterprises in the supply chain can be obtained through backward induction. The specific calculation process is detailed in the appendix, and the detailed expressions of each equilibrium result are shown in Table A1. To ensure the non-negativity of the research results and to avoid other trivial situations, we need (0 ,<, b, <, barb). Furthermore, before discussing the different investment strategies of the manufacturer, we first need to clarify the conditions under which it is profitable for the manufacturer to invest in the emerging supplier, thereby ensuring that all subsequent analyses are feasible. This leads to Proposition 1.

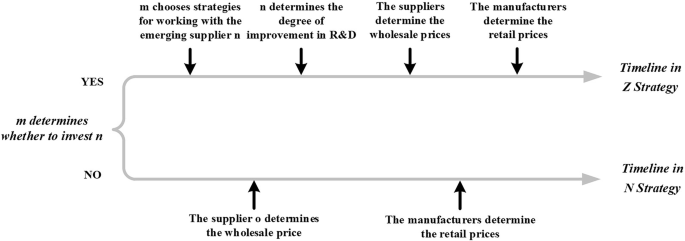

Proposition 1. There exists a threshold (underlineb, > ,0) such that the manufacturer m chooses to invest in the emerging supplier n if and only if (ble underlineb), as shown in Fig. 3.

Proposition 1 indicates that when (b) exceeds a certain threshold, the manufacturer has no incentive to invest in the emerging supplier, but instead chooses to share an established supplier with a competitor. This is because, in highly competitive markets, the manufacturer prefers to maintain the stability of their existing supply chains, avoiding the uncertainties brought by investing in the emerging supplier, as shown in the white area of Fig. 3. When (b) is below a certain threshold, the manufacturer will choose to invest in the emerging supplier, as shown in the red area of Fig. 3.The reason lies in the fact that under lower competitive pressure, the manufacturer has more room to pursue higher profits and product innovation (de Bettignies et al. 2023). Investing in the emerging supplier can help the manufacturer gain unique technological advantages and more flexible supply chains, thereby achieving differentiated competitiveness in the market. Moreover, lower (b) also means that the market’s sensitivity to price may be lower, allowing the manufacturer to achieve higher profits through innovative products rather than merely relying on price competition. In such a market environment, the manufacturer tends to adopt more aggressive investment strategies, aiming to develop more innovative products in collaboration with the emerging supplier, thereby increasing market share and brand value. Therefore, we focus on the case when (ble underlineb) in the following analysis.

Note: the following parameter values are used: (kappa =0.49,beta =0.05)

Price and product improvement analysis

Lemma 1. The impact of (b) and (theta) on prices.

Lemma 1 (a) indicates that both wholesale and retail prices of products decrease with the increase in market competition intensity. This is also consistent with the traditional view that fierce market competition often forces enterprises to attract and retain consumers through price adjustment, thus forming an overall trend of price decline (He et al. 2019). Like the intensity of market competition, the probability of R&D success also hurts the price, as shown in Lemma 1(b). As the probability of R&D success increases, the wholesale price of both suppliers will decrease. This is because the increase in the probability of R&D success not only intensifies the competition among suppliers but also enhances the bargaining power of manufacturers, thus adjusting market expectations. Under the combined action of these factors, the established supplier and the emerging supplier must reduce wholesale prices to provide more favorable purchasing conditions to expand their market share. For manufacturers, the increased probability of R&D success will also intensify competition, and the reduction of wholesale prices means that manufacturers have more profit margins, so they have enough incentive to reduce retail prices (Zhang et al. 2024). For example, in the home appliance industry, as the maturity of OLED technology enables TV manufacturers to produce thinner and more colorful screens, while increasing the yield of production, the competition between brands such as Samsung, LG, SONY, etc., has become increasingly fierce, resulting in the wholesale and retail prices of TV sets are falling (PConline 2015).

Lemma 2. The effect of (b) and (theta) on the degree of product innovation.

Lemma 2(a) indicates that the degree of product improvement by the emerging supplier will increase with the intensity of market competition, but this effect will vary depending on the investment model. Specifically, under LI, the emerging supplier needs to bear higher financial risks and the pressure of repaying loans on their own. To avoid potential financial difficulties, the emerging supplier often tends to choose low-risk R&D projects, thereby suppressing the potential for product improvement. Under EI and CS, the manufacturer can share some of the R&D risks with the emerging supplier, motivating them to pursue product innovation (Zhang and Lee 2022). At the same time, while a high probability of successful R&D can facilitate the launch of new products, it may lead enterprises to adopt more conservative R&D strategies, thereby reducing the extent of improvements. This phenomenon seems counterintuitive, but it can be understood in this way: although a high success rate in R&D is beneficial for the launch of new products, it does not necessarily indicate a significant improvement in product quality. On one hand, a high probability of R&D success often means that the company has adopted a relatively conservative strategy during the R&D process, which may sacrifice a certain degree of innovation and breakthroughs (Lévesque 2000). Additionally, a high probability of success may also trigger incentive compatibility issues. In situations where the likelihood of success is high, the supplier might reduce their extra efforts because they believe that even without significant improvements, successful R&D is still possible. This behavior further diminishes the extent of product improvement. Therefore, to address the challenges, enterprises need to balance market competition and R&D risks through appropriate investment models and incentive mechanisms. Manufacturers, should choose suitable investment models based on the intensity of market competition and incentivize suppliers to innovate through risk-sharing mechanisms; meanwhile, suppliers need to find a balance between innovation and stability to achieve optimal R&D investment strategies. At the same time, enterprises in R&D management should avoid excessively pursuing R&D success rates and can encourage moderate high-risk R&D activities to drive more significant product improvements.

Lemma 3. The impact of other key parameters on wholesale prices, product prices, and product innovation, as shown in Table 3.

Lemma 3 shows that the shareholding under EI and the share ratio under CS have the same influence on the product price and the product innovation degree. With the increase in shareholding (share) ratio, the wholesale price of the emerging supplier, the retail price of the competitor, and the innovation degree of products will increase, the wholesale price of the established supplier will decrease, and the change of the manufacturer’s retail price will be affected by the success rate of R&D. The reason for this is that a higher shareholding (share) ratio means a closer cooperative relationship between the manufacturer and the emerging supplier, which increases the incentive for both parties to jointly invest in product innovation (Guo et al. 2024). In addition, as the degree of cooperation deepens, the emerging supplier may have access to more resources and technical support, which also helps them raise the price of their products. However, this strategy may also lead the established supplier to lower the wholesale prices of their products to remain competitive in the market, as they may face greater competitive pressure from the emerging supplier. The manufacturer, will adjust retail prices according to the success rate of R&D. If a higher R&D success rate indicates that product innovation from the emerging supplier is more likely to be successful, the manufacturer will raise retail prices to reflect the improvements and added value. Conversely, if R&D success rates are low, the manufacturer will lower retail prices to attract consumers and maintain market share.

Different from the above two strategies, with the increase of loan interest rate, the wholesale price of the emerging supplier, the retail price of the competitor, and the innovation degree of products will decrease, while the wholesale price of the established supplier will increase, and the change of the manufacturer’s retail price is still related to the success rate of R&D. This is because the loan investment increases the financial pressure on the emerging supplier, placing them solely responsible for the repayment of loans and the risk of R&D failure, so they invest less in product innovation. This financial pressure is further exacerbated by higher lending rates, which lead to lower wholesale prices and product innovation for the emerging supplier. At this time, since the products of the emerging supplier are not very competitive, the established supplier may take advantage of this to raise their wholesale prices because their product supply is more stable. The manufacturer, faced with a lower degree of product innovation and possible supply chain instability, also needs to adjust their retail price strategies to balance market demand and cost pressures.

Proposition 2. Comparative analysis of wholesale prices:

-

a.

If (0 ,< ,kappa ,< ,fracbbeta (3-2theta )^254(1-beta )), then (w_n^C* , > ,w_n^E* , > ,w_n^L* ); otherwise, (w_n^E* ge w_n^C* ,>, w_n^L* ).

-

b.

If (0, < ,kappa ,< ,beta), then (w_o^L* , > ,w_o^E* , > ,w_o^C* ); otherwise, (w_o^L* , > ,w_o^C* ge w_o^E* ).

Proposition 2 compares the wholesale prices of products from two suppliers under different investment strategies. The results indicate that under LI, the wholesale prices of the emerging supplier are consistently the lowest, while the wholesale prices of the established supplier are consistently the highest. This is because, under LI, the emerging supplier faces higher financial pressure and needs to attract manufacturers’ orders with lower wholesale prices to ensure they can repay loans and cover higher capital costs. The established supplier, due to their stable market position and lower capital costs, can maintain higher wholesale prices. Under EI and CS, the size of the shareholding ratio directly affects the degree of risk-sharing between the manufacturer and the emerging supplier. A higher shareholding ratio means that the manufacturer has greater economic interests in the success of the emerging supplier and is therefore willing to accept higher wholesale prices to support the emerging supplier’s investments in R&D and product quality improvements. In this case, the emerging supplier may raise wholesale prices to reflect the value of their product improvements and technological innovations. When the manufacturer chooses LI, if product development is successful, they can not only gain a significant competitive advantage in product quality but also have greater price advantages compared to the other two strategies. We refer to this phenomenon as the procurement advantage under LI chosen by the manufacturer, which is also the positive force driving the manufacturer to prefer loan investment.

Proposition 3. Comparative analysis of product prices:

Proposition 3 compares the retail prices of products from two manufacturers under different strategies. Interestingly, when (theta) is low, the retail price of the manufacturer under LI is the highest, whereas when (theta) is high, the retail price of the manufacturer under LI is the lowest. Here, we can combine Proposition 2 to see that when (theta) is high, under LI, the emerging supplier provides products at the lowest wholesale prices. At the same time, successful R&D enhances the competitiveness and market demand for the manufacturer’s products. In this case, the manufacturer can capture a larger market share by lowering retail prices, thereby achieving higher overall revenue. When (theta) is low, although the wholesale prices of the emerging supplier under LI remain very low, due to the uncertainty of R&D, the manufacturer may have to procure from the established supplier with higher wholesale prices, leading to an overall increase in procurement costs. To mitigate this risk, the manufacturer will choose to raise retail prices to cover costs and potential losses. This phenomenon of retail price reversal reflects the profound impact of the probability of successful R&D on supply chain cost distribution and market strategy. For the competitor, regardless of the success rate of product development, their retail prices under the manufacturer’s implementation of loan investment are always the highest. This indicates that loan investment can provide the manufacturer with a significant competitive advantage. Specifically, the manufacturer can leverage the innovative capabilities of the emerging supplier to launch higher-quality products, thereby further enhancing their market competitiveness. In contrast, the competitors, unable to directly benefit from the low costs and technological innovation support of emerging suppliers, must maintain their profit levels with higher retail prices.

Therefore, when the various technologies of a product are not mature, the manufacturer’s use of loan investment may have adverse effects on consumers, as this strategy often leads to higher retail prices when the probability of successful R&D is low, thereby increasing the cost of purchase for consumers. In this situation, the government should appropriately intervene by formulating relevant policies to balance the market and protect consumer interests. For example, it could provide R&D subsidies and low-interest loans to upstream enterprises, reducing their financial burden while encouraging them to continue investing in technological research and development, thereby increasing the success rate of product development.

Proposition 4. Comparative analysis of the degree of product innovation:

Proposition 4 indicates that under LI, the degree of product improvement is always the lowest, while the degree of improvement under the other two strategies depends on the manufacturer’s shareholding ratio. If (kappa) is high, the product improvement degree is highest under EI; otherwise, the product improvement degree of the emerging supplier is highest under CS. This also aligns with our intuition. Loan investment has increased the financial pressure on the emerging supplier, forcing them to bear the responsibility of loan repayment and the risk of R&D failures on their own, thereby reducing their investment in product quality improvement. For example, Powa Technologies, once considered the future of the payment industry, faced increasing financial pressure because its operating costs relied heavily on borrowed capital. Due to its inability to continue effectively improving and innovating its payment technology, Powa Technologies ultimately went bankrupt in 2016 (News 2016). In contrast, under EI and CS, the degree of product improvement is influenced by the manufacturer’s shareholding ratio and the cost-sharing ratio. If (kappa) exceeds a certain threshold, it means that the cooperation between the manufacturer and the emerging supplier is closer, and the manufacturer has greater incentives and resources to support the emerging supplier in product improvement. Therefore, under EI, the degree of product improvement is the highest (Haw et al. 2023). Similarly, when the manufacturer bears a larger share under CS, the emerging supplier may be more willing to invest in product innovation due to reduced cost pressure.

Compared to the other two strategies, the manufacturer implementing loan investment is not conducive to product improvement, indicating an innovation disadvantage. This may be a positive force for the manufacturer to prefer the other two investment strategies. Therefore, for industries that require continuous innovation, such as high-tech and new energy, it may not be a wise move for the manufacturer to adopt a loan strategy to invest in the emerging supplier, as this would limit product innovation and affect the enterprise’s long-term competitiveness and market position.

Analysis of investment strategy

Proposition 5. Comparative analysis of suppliers’ expected profit:

Proposition 5 indicates that the emerging supplier prefers EI or CS, depending on the size of the manufacturer’s stake, while the established supplier consistently prefers LI. No matter what investment strategy the manufacturer chooses, the expected profit of the two suppliers cannot be optimal at the same time. In addition, combined with Proposition 4, the strategic preferences of the emerging supplier are closely related to the degree of product innovation, and the higher the degree of product innovation under any strategy, the greater the expected profit of the emerging supplier. Therefore, for an emerging supplier, on the one hand, should actively negotiate with the manufacturer and avoid LI. At the same time, pay close attention to the size of the shareholding proportion of the manufacturer under EI, and find the best way to cooperate. On the other hand, we should always pay attention to product innovation, to maximize its benefits.

Proposition 6. The manufacturer’s investment strategy choice for the emerging supplier:

(left.aright),Ifmax b_3,b_4\le b,the; manufacturer; chooses; loan; investment; strategy.)

(left.bright),Ifleft\beginarrayc ,beta le kappa ,< ,1/2\ b_2le b ,< ,b_4endarrayright.orleft\beginarrayc ,0 ,< ,kappa ,< ,beta \ ,0 ,< ,b ,<, b_1endarrayright.,the; manufacturer; chooses; cost; sharing; strategy.)

(left.cright),If,left\beginarrayl0 ,< ,kappa ,< ,beta \ b_1le b ,< ,b_3endarrayorleft\beginarraycbeta le kappa ,<, 1/2\ 0 ,<, b ,<, b_2endarrayright.,,the; manufacturer; chooses; equity; investment; strategy.right.)

For the expressions of thresholds (b_1), (b_2), (b_3) and (b_4), see Appendix D.

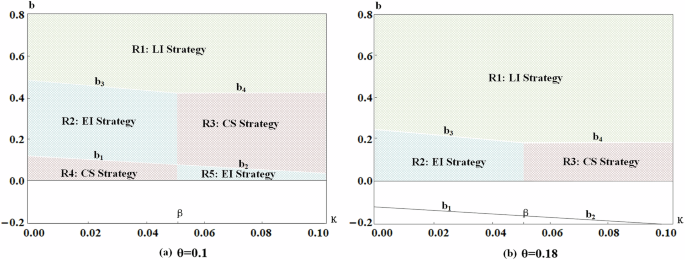

Proposition 6 shows the optimal investment strategy for the manufacturer in different situations, and this interesting result arises from the interaction of two parameters, as shown in Fig. 4. When the market competition intensity is high ((mathrmmaxb_3,b_4\le b)), the manufacturer will choose LI, as shown in R1 in Fig. 4a. This is because, in a highly competitive market environment, the manufacturer not only needs to improve product quality to seize market share but also to avoid the risk of R&D failure. LI allows the manufacturer to participate in the R&D activities of the emerging supplier with lower risk while placing more of the risk of R&D failure on the shoulders of the emerging supplier. Second, when the market competition intensity is appropriate ((b_1le b ,<, b_3) or (b_2,le, b ,<, b_4)), the manufacturer’s strategy choice will consider more about the depth of cooperation and risk-sharing mechanism with the emerging supplier. In this case, the shareholding ratio becomes the key factor. If the shareholding ratio is less than a certain threshold, EI is selected, as shown in R2 of Fig. 4a. Otherwise, choose CS, as shown in Fig. 4a. Finally, when the market competition intensity is relatively small ((0 ,<, b ,<, b_1) or (0 ,<, b ,<, b_2)), although the manufacturer’s strategy selection still depends on the size of the shareholding ratio, interestingly, if the shareholding ratio is greater than a certain threshold, EI is selected, as shown in R5 of Fig. 4a. Otherwise, CS is selected, as shown in R4 of Fig. 4a. This result reflects the manufacturer’s strategy choice logic under different market competition environments. Specifically, when the intensity of market competition is low, the manufacturer can bear more R&D risks and is therefore willing to obtain potentially high returns on investment with high equity. When market competition is moderate, the manufacturer needs to find a balance between depth of cooperation and risk sharing. In general, this change reflects the logic of the manufacturer’s strategy selection in different market competitive environments. When the competition is moderate, the manufacturer pays more attention to risk control and flexibility to maintain long-term stable development; When competition is small, the manufacturer is more inclined to respond to competitive pressure through deep cooperation. This is also reflected in the studies of de Bettignies et al. (2023) and Guo et al. (2024).

In addition, it can be seen from Fig. 4b that when (theta) increases, the regions of EI and CS will shrink, while the regions of LI will increase. With the increase in the probability of R&D success, the manufacturer will be more inclined to choose LI. The reason for this phenomenon is not difficult to understand, as shown in Lemma 2, the increase in the success rate of R&D will lead to the weakening of the degree of product improvement of the emerging supplier, that is, the decline of product competitiveness. Although the products of the emerging supplier still have a certain competitive advantage currently, due to the disadvantage of unstable supply, manufacturers choose risk-sharing strategies (such as CS and EI) to obtain more stable and significant returns than the loan investment.

Note: the following parameter values are used: (r=0.5,beta =0.05)

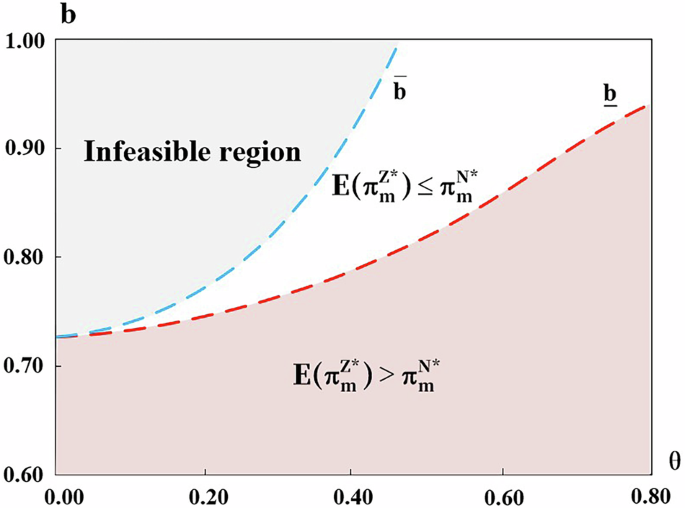

Proposition 7. The competitor’s investment strategy preferences for the manufacturer:

For the expressions of thresholds (b_5) and (b_6), see Appendix D.

Proposition 7 demonstrates competitors’ investment strategy preferences for the manufacturer. When the R&D success rate is low, the competitor’s strategic preferences mainly depend on the market competition intensity and the manufacturer’s shareholding ratio, as shown in R4, R5, and R6 in Fig. 5. Currently, due to the low success rate of research and development, the products of the emerging supplier in the market are relatively uncertain, and the competitor needs to comprehensively consider the intensity of market competition and the shareholding ratio of the manufacturer to evaluate their market position and risk tolerance. When the R&D success rate is moderate, the competitor’s strategic preference depends only on the manufacturer’s ownership, as shown in R2 and R3 in Fig. 4. At this stage, the improvement of the R&D success rate increases the success probability of the emerging supplier’s products, and the intensity of market competition is relatively fixed. The competitor pays more attention to the shareholding ratio of the manufacturer because it directly affects the manufacturer’s support for the emerging supplier’s products and market share allocation. When (theta) is high, the competitor always prefers the manufacturer to adopt the loan investment strategy, as shown in R1 in Fig. 5. This is because in the case of a high R&D success rate, product improvement and innovation are more stable, compared with other strategies, the manufacturer uses LI return structure is more stable, and provides a relatively stable and predictable market environment for the competitor. With the increase of R&D success rate, the competitor’s strategy preference gradually changes from multi-factor influence to single-factor influence, until stable. This trend reflects that under the high success rate of R&D, the uncertainty of market competition is reduced, and the competitor is more inclined to seek a stable and predictable market environment, and the loan investment strategy just meets this demand. As a result, the competitor’s strategic preferences become more focused and defined as R&D success rates improve.

Note: the following parameter values are used: (r=0.5,beta =0.05)

Consumer surplus and social welfare analysis

Under market competition and R&D uncertainty, manufacturers’ investment strategies can affect product innovation and pricing, thereby altering consumer purchasing decisions and willingness to pay, impacting consumer surplus. At the same time, these strategies can also have profound effects on supply chain efficiency, cost distribution, and profit structure, ultimately affecting the distribution of social welfare. Comparing consumer surplus and social welfare under different investment decisions helps to comprehensively evaluate the pros and cons of investment strategies, provides theoretical support for manufacturers to make more socially responsible decisions, and offers references for the government to optimize policies to maximize social welfare.

Here, consumer surplus refers to the total sum of all surplus from consumers when the product development is successful or when it fails. Social welfare includes the expected profits of upstream and downstream enterprises, as well as consumer surplus. Consistent with the study by Li et al. (2020), the expressions for consumer surplus and social welfare are:

Proposition 8. Comparative analysis of consumer surplus:

Proposition 8 indicates that under LI, consumer surplus is always the lowest, while under EI and CS, consumer surplus depends on the manufacturer’s shareholding ratio. When the manufacturer’s shareholding ratio is higher, the consumer surplus under EI is the highest; conversely, the consumer surplus is highest under CS. This conclusion is not difficult to understand—combining the aforementioned propositions 2–4, it is clear that LI will increase the financial costs for the manufacturer, and these costs are usually passed on to consumers by raising product retail prices, thereby reducing consumer surplus. In contrast, EI and CS can more effectively balance the distribution of benefits between the manufacturer and the emerging supplier, making them more favorable to consumers. Specifically, when the manufacturer’s equity stake is high, EI can incentivize the manufacturer to closely collaborate with the emerging supplier, driving product innovation while helping to reduce overall supply chain costs, making product prices more competitive, and thereby increasing consumer surplus. Conversely, when the manufacturer’s equity stake is low, CS enables the manufacturer and the emerging supplier to jointly bear R&D and production costs. This cost-sharing mechanism reduces the financial pressure on either party, allowing manufacturers to offer more attractive prices, thereby further enhancing consumer surplus. Therefore, from the consumer’s perspective, encouraging enterprises to adopt EI or CS is clearly more beneficial to consumer interests, as it can both promote innovative cooperation between enterprises and provide the market with more cost-effective products.

Proposition 9. The comparative results of social welfare under different investment strategies are summarized in Table 4.

For the expressions of thresholds (rmb_5) and (rmb_6), see Appendix D.

Proposition 9 emphasizes three main factors in the comparison of social welfare under different investment strategies, namely the probability of successful product development, the intensity of market competition, and the manufacturer’s shareholding ratio. Table 4 details the relationship between the magnitude of social welfare and these factors. Based on the analysis of Table 4, we have the following two main findings: fFirst, as the probability of successful R&D increases, when social welfare is optimal, the investment strategy will show dynamic changes. The overall trend shows that when the probability of successful R&D is low, LI may bring greater social welfare; whereas when the probability of successful R&D is high, the socially optimal investment strategy gradually shifts towards EI or CS. This change is mainly influenced by the proportion of shares held by the manufacturer. Secondly, when market competition is low, load investment can bring higher social welfare. However, it is worth noting that in the case of low market competition, the manufacturer is more inclined to choose EI or CS to maximize their own profits (see Proposition 6). This indicates that the investment strategies chosen by the manufacturers in pursuit of profit maximization may conflict with achieving optimal social welfare. It is evident that the profit-oriented goals of the manufacturer are not entirely aligned with the objectives of social welfare. Therefore, the government should intervene in a timely manner, using policy regulation to guide manufacturers toward investment strategies that better align with the optimization of social welfare. For example, the government can encourage manufacturers to adopt equity investment or cost-sharing strategies when the probability of successful R&D is high by providing tax incentives, R&D subsidies, and other incentives, thereby promoting the maximization of social welfare. At the same time, the government can also strengthen the regulation of market competition to ensure fairness and transparency in market competition, preventing manufacturers from harming social welfare in pursuit of their own interests.

Extensions

Enhance the impact of the innovative R&D capabilities

In the basic model presented in this paper, manufacturers do not interfere too much in the R&D and innovation process of the emerging supplier, so the innovative R&D capabilities of the emerging supplier under the three investment strategies are the same. However, we have also observed that some manufacturers are using their market insights and technical expertise to make R&D easier for suppliers when adopting the cost-sharing strategy (Zhang et al. 2015; Yang et al. 2023). Because the manufacturer is closer to the market, they can identify customer needs, predict market trends, and provide feedback on this information to the supplier, to guide the direction of research and development and enhance the ability to research and innovate. For example, when Tesla, Inc. partnered with Panasonic to develop electric vehicle batteries, it used its insights into the electric vehicle market and deep understanding of battery technology to help Panasonic optimize battery design and production processes, accelerating the development of new batteries (EE Times China 2021). Therefore, we assume that the innovative R&D capability of the emerging supplier under the cost-sharing strategy is (k,(0 < k < 1)), which is unchanged under other strategies, to explore the impact of enhancing innovative R&D capability.

The superscript (X) is used to represent this situation, where the expected profit of each member under the cost-sharing strategy is as follows:

The model was solved by backward induction. For specific results, see Table A2 in Appendix A. By comparing the expected profit of manufacturers, we can see:

Proposition 10. The manufacturer’s investment strategies for the emerging supplier under the enhancement of the innovative R&D capabilities:

For the expressions of thresholds (b_1^X), (b_2^X), (b_3^X) and (kappa _1), see Appendix D.

Proposition 10 compares the investment strategy choices of the manufacturer that enhance innovative R&D capabilities. The results show that when the market competition intensity is high, the manufacturer chooses to loan invest, and when the market competition intensity is low, the choice of investment strategy depends on the size of the shareholding ratio. If the shareholding is less than a certain threshold, the cost-sharing strategy is selected; if the shareholding is greater than a certain threshold, the equity investment strategy is selected. The conclusions of Proposition 7 are consistent with Proposition 5, which also indicates that our results are robust. In addition, we also find that the threshold of the shareholding ratio will increase with the decrease of (k), which means that under the cost-sharing strategy, the more help the manufacturer gives to the innovative R&D of the emerging supplier, the more inclined the manufacturer will choose the cost-sharing strategy, which is also consistent with the actual situation.

Impact of non-negative production costs

Improvements in product quality can often be accompanied by reductions in production costs during the actual innovative R&D process (de Bettignies et al. 2023; Zhang et al. 2024). For example, BOE has improved the performance of OLED screens by adopting low-temperature polycrystalline silicon oxide (LTPO) back sheet technology and stacked light-emitting device (LED) preparation processes through technological innovations, while achieving lower power consumption and longer service life, which not only enhances the competitiveness of its products but also contributes to the reduction of production costs (China news 2024). As a result, the success of innovative R&D by the emerging supplier not only results in higher product quality but also lower production costs. With this in mind, we explore the impact of non-negative costs of suppliers by making the production cost of the established supplier (c_1) and the production cost of the emerging supplier (c_2). Consistent with Niu and Wang (2024), we normalize (c_1=0) and let (c=c_2-c_1) denote the difference in production cost between two suppliers.

The superscript Y is used to represent this situation, where the expected profit of the established supplier is as follows:

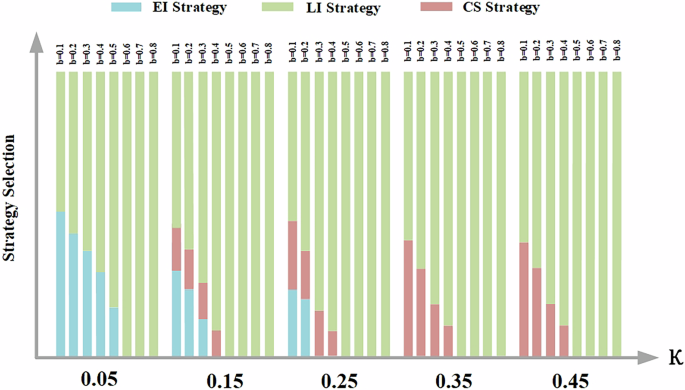

We still solve the model by backward induction, and the specific results are shown in Table A2 in Appendix A. Unfortunately, since the expression of expected profit is more complicated, it is difficult to draw valid conclusions directly from the comparative analysis, so we do extensive numerical studies on the investment strategy choices of the manufacturer. The manufacturer’s profit function is mainly affected by the following six parameters: (theta), (kappa), (b), (c), (r), (beta). The specific assignments are shown in Table 5. There is a total of 9 × 10 × 4 × 4 × 8 × 5 = 57,600 scenarios. Using MATLAB software for programming, the results of the assignment combinations of all parameters are collected and organized according to ((kappa ,b)), and finally, the strategy selection situation is obtained as in Fig. 6, where each data bar indicates the manufacturer’s strategy selection situation when ((kappa ,b)) is fixed.

Observation 1 suggests that our main findings are qualitatively unchanged. That is, when the intensity of competition in the market is high, the loan investment strategy is preferred, while when the intensity of competition in the market is low, the optimal investment strategy is related to the size of the shareholding. The difference is that the R4 and R5 regions in Fig. 4a do not occur when production costs are taken into account, because the increase in production costs of the established supplier leads to the need for these suppliers to increase the price of their products to maintain their profit margins, which indirectly leads to an increase in the intensity of competition in the market, thus rendering the specific investment strategies (such as those represented by the R4 and R5 regions) no longer viable in a low intensity of market competition.

Conclusion and implications

With the globalization of the economy and the intensification of competition in the market, manufacturers will join forces with their upstream suppliers to establish a technologically close supply chain, strengthen the degree of vertical integration between enterprises, optimize the allocation of resources between enterprises, and enhance their competitiveness. In practice, we do observe that manufacturers adopt equity investment, loan investment, and cost-sharing strategies to support emerging suppliers in product innovation. Different investment strategies provide different incentives for manufacturers and suppliers and have different potential impacts in terms of risk allocation, profit sharing, and cost-sharing. Therefore, the choice of which investment strategy to pursue becomes an important strategic decision for manufacturers to consider. Based on this, we develop a game-theoretic model to explore the manufacturer’s preferences for different investment strategies by considering the strategic interactions between market competition and R&D uncertainty. The main findings are as follows:

-

(1)

With the intensification of market competition and the improvement of R&D success probability, the manufacturer and the supplier will reduce product prices, which reflects the pressure of competition and technological progress on prices. From the perspective of innovation, market competition can encourage emerging suppliers to carry out more innovation, especially under the strategy of equity investment and cost-sharing, which can effectively share R&D risks and promote product innovation. However, the higher probability of R&D success may lead to the adoption of conservative strategies, which inhibits the innovation of products by the emerging supplier.

-

(2)

Compared with other strategies, under the loan strategy, the emerging supplier will set lower wholesale prices, while the established supplier will set higher wholesale prices, and correspondingly, the competitor will set higher retail prices. For the manufacturer, the level of retail price under the loan investment strategy depends on the success probability of product R&D. When the success probability of product R&D is low, the manufacturer will set a higher retail price to make up for the high risk and uncertainty and protect the possible R&D failure and high loan costs. When the probability of success is high, product innovation is more likely to be achieved, and the manufacturer will set lower retail prices to attract consumers.

-

(3)

The emerging supplier prefers equity investment or cost-sharing strategies, which mainly depend on the proportion of shareholding of the manufacturer. In contrast, the established supplier prefers the loan investment strategy, indicating that no matter which investment strategy the manufacturer chooses, both suppliers cannot achieve a win-win situation. For the competitor, its preference for manufacturer investment strategy varies with the change in R&D success rate. When the success rate of R&D is low, the competitor has preferences for the three strategies under certain conditions. However, when the R&D success rate is moderate, the competitor mainly decides its preferences according to the shareholding ratio of the manufacturer, and its strategic preference for the manufacturer is equity investment or cost sharing. When the R&D success rate is high, the competitor only prefers a loan investment strategy. In general, with the improvement of the success rate of R&D, the competitor’s strategic preference gradually changes from multi-factor influence to single-factor influence, that is, the manufacturer tends to choose investment strategies that can provide market stability.

-

(4)

The manufacturer’s investment strategies for the emerging supplier show obvious differences under different market competition intensities. In highly competitive markets, the manufacturer tends to choose the loan investment strategy to reduce its own risk and transfer the risk of R&D failure to the emerging supplier. When the market competition intensity is moderate, the investment strategy choice of the manufacturer will depend more on the depth of cooperation and risk-sharing mechanism with the emerging supplier. Currently, the shareholding ratio becomes the key factor of decision-making: If the shareholding ratio is less than a certain threshold, the equity investment strategy is selected; otherwise, choose the cost-sharing strategy. In the environment of weak market competition, the manufacturer is more inclined to choose equity investment when the proportion of shares is large. In addition, the increase in the probability of R&D success may make the manufacturer more inclined to loan investment, because this strategy can still provide stable income when the degree of product innovation is low.

The above findings also provide some meaningful management insights in the following three areas. The first is balancing innovation and risk management: while pursuing product innovation, enterprises also need to focus on cost control and risk management. Through equity investment and cost-sharing strategies, enterprises can effectively share R&D risks and promote innovation. However, enterprises should also pay attention to the changes in the probability of R&D success to avoid the weakening of innovation incentives caused by a high probability of success. Management-wise, enterprises should establish flexible R&D budgets and risk assessment mechanisms to ensure that they can remain competitive in different market environments. The second is pricing strategy and market positioning: when developing pricing strategies, enterprises should consider their position in the supply chain, as well as the competitive market conditions. For the emerging supplier, a lower wholesale price may be needed to attract the manufacturer and gain market share under the loan strategy, while the established supplier can reflect their brand value and product quality through a higher wholesale price. The manufacturer should consider the probability of R&D success and the cost of a loan when setting retail prices to ensure that the price reflects the value of the product, as well as attracting consumers. On the management side, enterprises should conduct market segmentation and develop differentiated pricing strategies based on different markets and product development. The third is an investment strategy and cooperation mode: the manufacturer should consider factors such as market competition intensity, shareholding ratio, and R&D success probability when choosing an investment strategy. In a competitive market, the loan investment strategy may be more popular because it helps spread risk; in markets where competition is moderate or weak, equity investment or cost-sharing strategies may be more appropriate, as they help deepen partnerships and share success. In management, the manufacturer should establish long-term strategic partnerships with suppliers and adapt to market changes through flexible investment strategies. At the same time, we should pay close attention to the changes in the success rate of research and development to adjust the investment strategy in time to ensure that enterprises can maintain competitiveness and market stability in different market environments.

Limitations

This study mainly discusses the investment strategy selection of the manufacturer under the uncertainty of market competition and product innovation. The research results have certain theoretical value and practical significance, but there are also some limitations, which provide a direction for future research. First, it is intuitive that the emerging supplier’s products perform better after successful R&D, so the manufacturer may want to acquire new technologies to enhance their competitiveness and choose to work with the emerging supplier. Knowing this, the established supplier may also improve their products to enhance their market competitiveness. How does this decision affect the manufacturer’s investment strategies? How should the manufacturer choose in this case? These questions will make the research conclusions more complex and interesting, so future research will further explore these questions. Second, this raises the issue that the manufacturer faces new procurement decision challenges when the established supplier also makes product innovations. Its purchasing strategy may change as a result, should it choose dual-source procurement or single-source procurement? This issue also deserves further study.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

-