‘It’s death by a thousand cuts’: marine ecologist on the collapse of coral reefs

June 25, 2025

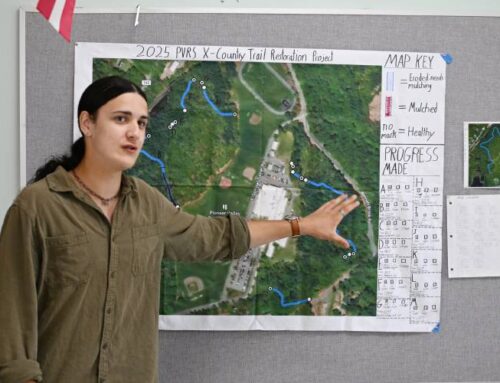

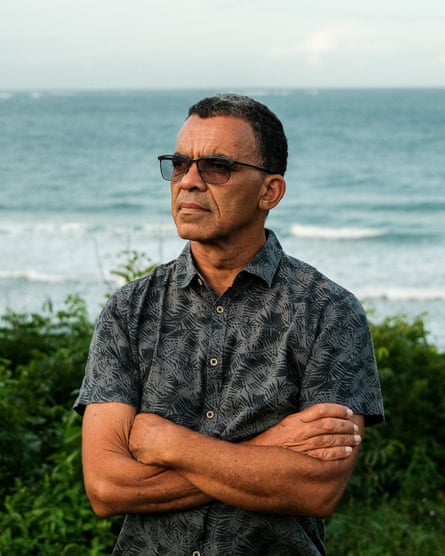

The Kenyan marine ecologist David Obura is chair of a panel of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), the world’s leading natural scientists. For many decades, his speciality has been corals, but he has warned that the next generation may not see their glory because so many reefs are now “flickering out across the world”.

Why are corals important?

Multiple reasons. They are home to a huge amount of biodiversity, which provides food and environmental services. They also serve as coastal buffers, protecting coastlines from storms and swells. In many ways, coral are like underwater forests. The algae living inside corals are photosynthetic and grow very much like trees. Together, they are the ecosystem architects, and if you lose those, you lose the entire ecosystem.

What is happening to coral reefs?

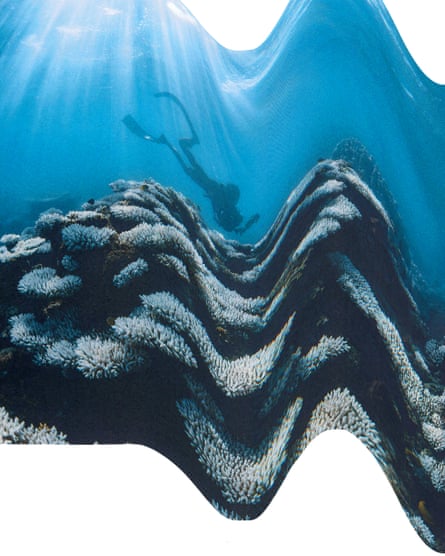

There are sudden collapses and also long linear declines. It depends on the circumstances. Climate change and pollution are really changing the background environmental conditions that coral reefs need to survive in. And then through fishing and other exploitation, a lot of their biomass is being extracted. There are so many of these different pressures happening at the same time that it’s a death by a thousand cuts. In the end, you lose the interactions and the complexity that characterises a coral reef. Half of the total area of live coral has been lost already. Many reefs no longer support the diversity and abundance that they used to.

When scientists talk about a tipping point for coral reefs, what do they mean?

Tipping points occur when the characteristics of a given system cease to exist. In the case of coral reefs, that happens due to a loss of the diversity and abundance of different species. At a certain point, this leads to the breakdown of the functions and the ecosystem processes of the entire system and if you don’t have any of those, then you don’t have a coral reef any more.

For people who are not experts, what are the signs of a collapsing reef system?

Firstly, less colour, because there’s less coral and other brightly coloured invertebrates. Instead, drab algae tend to dominate, and other invertebrates, such as sponges.

Then in the water, you see less abundance and diversity of fish. What you hear is also very different: on a vibrant coral reef, there are so many sounds, it is just like walking through a forest and listening to all the insects and birds. But a degraded, simpler reef has fewer animals making sounds, and they sound deathly quiet.

Finally, the three-dimensional structure breaks down. This may only take 10 years or so and then all the complexity is gone.

Where is this most pronounced?

It is easier to say where it is not pronounced. The last major holdout is perhaps the “Coral Triangle” in the Indonesian-Philippine archipelagos. It shows some resilience, though even there some places are strongly impacted because of local threats or climate change. In almost every other region, you’re seeing declines in coral cover and diversity and a loss of abundance and diversity of fish and invertebrates. That weakens the general health of the reef systems, and makes them more vulnerable to diseases and microbial activity, which are very harmful to coral species.

The most pronounced losses are probably in the Caribbean because it’s a smaller sea; a regional basin surrounded by land-based impacts. That’s also true of the Persian-Arabian Gulf, where there are many places that may no longer be called coral reefs. Whole regions are now vulnerable to ecosystem collapse and specific corals within them are increasingly endangered.

How close are coral reefs to a tipping point or has this already happened?

There’s a huge amount of discussion about that. Should we consider a tipping point at a small local scale, or at the level of an island or a coastline, or a region or the whole world?

Certainly it is already evident at a local scale; many reefs across the world have passed a point of no return. At the regional scale, I think the Caribbean may have tipped as an integrated coral reef system, even though there are locations that are still very vibrant, like the Mesoamerican barrier reef and some of the islands. All the coral reef regions that have so far been assessed on the red list of ecosystems have been classed as threatened, which means there is a high risk they may collapse within a 50-year period – unless the right actions are taken.

How much global heating do scientists estimate coral reefs can withstand?

We have recently revised the temperature threshold. Up to 2022, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) said the tipping point for coral reefs would occur when warming is between 1.5C and 2C above preindustrial levels. But in 2023, we revised that to between 1C and 1.5C. The world is already close to that upper limit and it will certainly come within the next 10 or 20 years as a result of committed climate change – which comes from cumulative emissions that have already gone into the atmosphere. So have we already gone past the tipping point for coral reefs in global terms? Perhaps.

What are the consequences?

The most obvious is the loss of the physical presence of coral reefs, their diversity of species and their functions. That has an effect on people because reefs protect coastlines and are habitats for fish that we eat. They are natural capital – assets that support our lives. When we lose coral reefs, we lose a lot of the foundations of societies and economies that depend on them.

Which fish depend on coral reefs?

Most affected are fish that eat or live in corals. They are mostly small, ornamental species, such as butterfly fish, damsel fish and things like that. But more importantly, corals provide the structure that sustains a much wider diversity of fish that eat algae, plankton, invertebrates and many other sources. All are impacted when the structure of the reef simplifies.

Are there any redeeming impacts?

Not at all. When coral cover goes down, it gets replaced by algae. Sometimes this can lead to an increase in herbivorous fish, because there’s more food for them. That may be good for fishing in the short-term, but any benefits disappear quickly as the three-dimensional structure of the reef declines.

Will this also affect people who don’t live near coral reefs?

They’ll feel it in many different ways. First, psychologically – instead of going on holiday to see beautiful coral reefs or getting messages from friends about their amazing colours and biodiversity, they will hear news of loss and decline. Second, there will be an economic impact. People won’t get fish on their plate from coral reefs, and tourism and coastal economies that depend on reefs will decline.

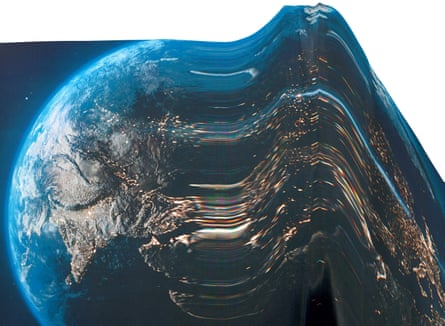

More broadly, the loss of corals will herald wider, systemic threats because corals are a canary in the coalmine for climate and other compounding threats. It means there will be a lot of other hidden tipping points, of other beautiful landscapes or the ecosystems that rural communities and even cities depend on. We’ve basically been using nature for free. If we had incorporated the cost of really caring for nature in our economies, we wouldn’t be in this situation right now.

Is there any way to restore corals?

Not yet at scale. Many techniques are being trialled, and many show promise – but they cannot replace what we are losing. There are now fewer and fewer healthy coral systems, more and more isolated from one another. The water is just getting too hot and too polluted, and there is too much extraction, all of which is punching big holes in the mosaic of reefs along our coastlines. Restoring coral reefs in this context is an uphill battle, and existing technologies are too difficult, and too expensive to apply at scale. What restoration does do is engage people in visible and tangible efforts to care for reefs, and this may deliver the greatest benefit, to finally build commitment to conserve coral reefs much more broadly.

What about experiments to artificially grow coral? Is there any hope of a technological solution?

There are a lot of trials, and many innovations. I’m a scientist, so I think we always need research into new techniques, otherwise we’ll never discover them. But the thing that I am adamant about, particularly coming from Africa, is that money that would go into community development and local resilience and building up low-income communities should not be going into the pockets of researchers and consultants doing artificial coral restoration. Research funding could and should be available, but we have to be very conscious of the rights and the equity issues around hi-tech fixes – who benefits and who doesn’t.

Putting aside scientific knowledge acquisition, how do you feel about the state of the world’s corals?

Angry, more than anything else. I want to point my fingers at the people who are responsible so they change what they’re doing. It’s not the billions of poor people around the planet; they face local challenges and environmental degradation, but they don’t have a global footprint. The global footprint that is causing a decline of corals and so much else is from the much smaller number of high-income consumers and economies. Until that is understood and they transform what they’re doing, we won’t be able to resolve the challenges at the bottom end of the income pyramid. You, in the global north, have to change what you’re doing in order for there to be an option for better futures, rather than just giving up and letting the worst futures come about. This is my mission now – to make waves for change.

Tipping points: on the edge? – a series on our future

Tipping points – in the Amazon, Antarctic, coral reefs and more – could cause fundamental parts of the Earth system to change dramatically, irreversibly and with devastating effects. In this series, we ask the experts about the latest science – and how it makes them feel. Tomorrow, Carlos Nobre talks about his fears for the Amazon rainforest’s future

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post