Lawmakers worldwide want to talk to the Meta insider whose memoir is a US bestseller – after Zuckerberg took her to court

March 25, 2025

Ironically, Mark Zuckerberg’s attempts to muzzle his former employee, Sarah Wynn-Williams, once director of global public policy at Meta, seem to have created a bestseller.

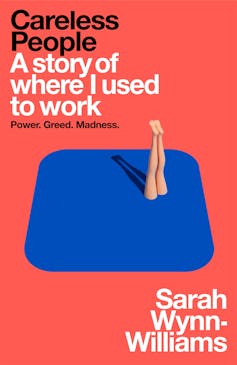

While Meta’s legal action successfully prevented Wynn-Williams (who worked there from 2011–17) from promoting her memoir, Careless People, her publisher has continued to promote it without her.

In the week of its release, the book sold 60,000 copies in the United States. In the United Kingdom, it sold 1,000 copies a day for the first three days.

“This early success is a triumph against Meta’s attempt to stop the publication of this book,” Joanna Prior, CEO of publisher Pan Macmillan, told the Guardian last week.

The court order that prevents Wynn-Williams from promoting her memoir may also prevent her from responding to requests from lawmakers in several countries to discuss her time at the company, formerly known as Facebook, and “issues of public concern”, her lawyers believe.

Requests have come from members of the US Congress, the parliament of the UK, the parliament of the European Union and other sources, reports CNN.

This comes as Zuckerberg, the founder, chairman and CEO of Meta, has committed the company, as Trump’s second term begins, to “free expression”. “Too much harmless content” is being censored, he says. In practice, this means getting rid of fact-checkers, in favour of a Community Notes program like the one on X, which Zuckerberg cites as a model.

Julia Demaree Nikhinson/Pool/AAP

Meta claims Wynn-Williams, a former diplomat born in New Zealand who convinced the company to create her global position, has broken a non-disparagement agreement: signed, it says, after she was dismissed for poor performance. Last week, it called the book

a mix of out-of-date and previously reported claims about the company and false accusations about our executives.

A true insider account

Last year, tech journalist Kara Swisher, in her memoir Burn Book, summed up Zuckerberg as “one of the most carelessly dangerous men in the history of technology” – interestingly, given this memoir’s title. She also referred to Facebook as “anti-social media”.

There have been other books about the company too, such as Facebook: the Inside Story by tech journalist Steven Levy in 2020 and An Ugly Truth: Inside Facebook’s Battle for Domination by journalists Sheera Frenkel and Cecilia Kang in 2021.

Some of the company’s misdeeds were discussed in these books. But whereas they are based on interviews with unnamed sources, Wynn-Williams, a senior insider, has put her name to them. She refers to the protagonists by their first names, reflecting the rapport they once shared.

Facebook/AAP

From shark attack to Facebook

Careless People starts with Wynn-Williams’ story of narrowly surviving a shark attack as a child, despite the complacency of her family and the local doctor. This may be to indicate her strength and resolve. Or perhaps it is a metaphor for the viciousness and indifference she would later encounter at Facebook.

She was initially a big fan of the company, which she saw as a potential force for good. An example of the good work of Facebook in its early days was a randomised control experiment before the 2010 US midterm elections. Some subscribers were sent a message at the top of their newsfeed encouraging them to vote, with a link to polling places and an “I voted” button they could click. This led to an additional 340,000 voters.

Every employee joining Facebook was given a Little Red Book written by Zuckerberg. As Wynn-Williams comments, the book represents “core principles from the supreme leader” who she calls “another MZ channeling his own peculiar form of Maoist zeal”.

Over time, Wynn-Williams’ admiration for Zuckerberg would wane. Her book is also rather unflattering about Sheryl Sandberg, Zuckerberg’s then deputy. The Lean In author is described as drawing people in “like moths to a flame” and expecting female staff to spend evenings helping to promote her book. This was particularly galling, as her book was about empowering women in the workplace.

Sandberg was such a demanding boss, Wynn-Williams was sending her talking points for a meeting at Davos while giving birth. Her doctor was saying: “you should be pushing – but not pushing ‘send’!”

Jean Christophe Bott/AAP

Losing faith and breaking things

Wynn-Williams started to question her faith in Facebook (which changed its name to Meta in 2021) when she realised parents working there did not allow their own teens to have mobile phones. “These executives understand the real damage their product inflicts on young minds,” she writes.

In 2017, an internal memo revealed Facebook was offering advertisers the opportunity to target teenagers when their posts revealed low self esteem. For example, beauty products could be targeted to young women when they deleted a selfie. The company was increasingly adding features that were “addictive by design”, as they sought to maximise engagement at all costs.

The company was adopting an aggressive stance towards traditional media. Zuckerberg attacked one of his staff for “compromising with a dying industry rather than dominating it, crushing it”.

In its drive for global domination, Facebook thought, in the words of one senior colleague, that “the first billion users are the easy billion”. Beyond that, there were the technical problems of expanding into countries with low or poor internet coverage. There were also ethical questions about collaborating with autocratic governments.

Wynn-Williams was perturbed when Facebook told China it could help “promote safe and secure social order”.

A United Nations investigator described how Facebook played a critical role in spreading hatred of Rohingya and Muslims within Myanmar. In 2018, the chairman of the UN Independent International Fact-Finding Mission on Myanmar told reporters that Facebook “substantively contributed to the level of acrimony and dissension and conflict” in the public, including “hate speech”.

Ted S. Warren/AAP

She also worried about the role Facebook played in the first election of Donald Trump, in 2016. It allowed the Trump campaign to target misinformation to people it would most likely influence, she writes. The campaign also used it to discourage groups less attracted to Trump from voting. She was disgusted when Zuckerberg, rather than being upset about this, admired “the ingenuity” of Trump’s campaign.

After a meeting with President Barack Obama, Zuckerberg was furious at being accused, accurately, of not taking seriously the problem of untrue stories being widely promoted.

The author warns that, unlike the global leaders he increasingly mixed with, Zuckerberg (now aged 40) could stay in his current position “for another fifty years”. His potential longevity is compared to Queen Elizabeth II.

At one stage, Zuckerberg seemed to be musing about a presidential run. Unlike Elon Musk, Zuckerberg was born in the US, so is eligible. But as Levy put it in his book, “no country on Earth has a population as big as Facebook; the presidency would be a step down”.

Unanswered questions

Wynn-Williams feels this emphasis on maximising profits at all costs is unnecessary. Had they wished, the senior people at the company could have been incredibly rich while still displaying some basic human decency.

Meta’s famous slogan is “move fast and break things”. But increasingly, Wynn-Williams concluded one of the things being broken was community health.

The book is easy to read and the author writes engagingly. But unanswered questions remain. Readers may wonder why the author stayed at Meta as long as she did once she developed misgivings about its impact.

She mentions her serious health issues: she feared losing her health insurance. But surely she had been on a large salary package and could afford to look after herself. She may have been in denial, unwilling to admit her initial admiration for Zuckerberg had been misplaced. Her husband’s explanation was she suffered from Stockholm syndrome.

The book would be a more useful reference if it had a bibliography and an index. But it does reveal some important insights about the attitudes of some careless –but very powerful – people.

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post