Meta’s AI drive could kill off social media

January 2, 2025

Meta’s AI drive could kill off social media

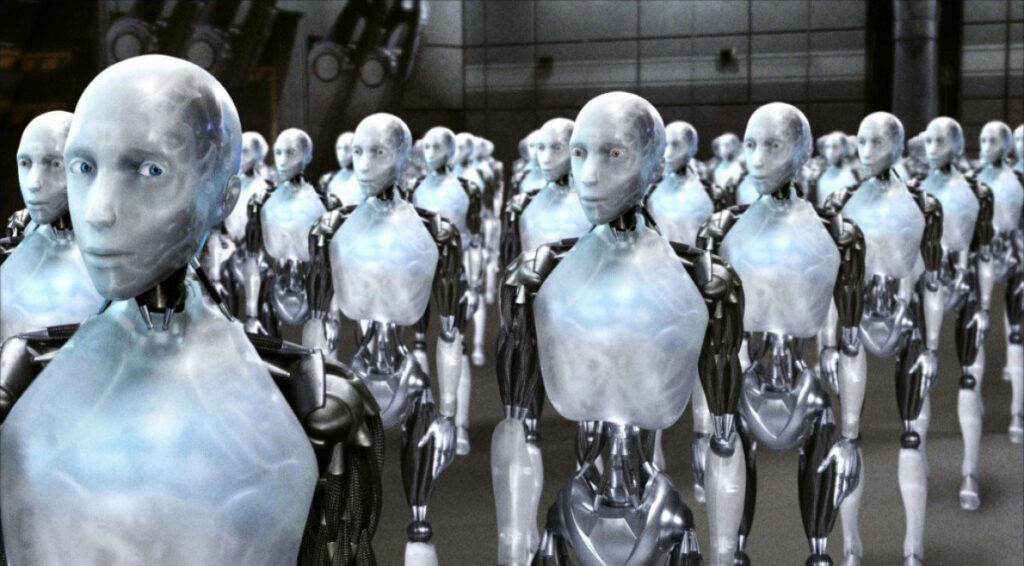

Your soon-to-be Facebook friends. Credit: Getty

Meta, the company behind Facebook and Instagram, has revealed plans to deploy millions of AI-generated “users” across its platforms. By late 2025, this initiative could transform Facebook and Instagram into something more closely resembling Character.AI than traditional social networks. Meta boss Mark Zuckerberg appears to be following Friend founder Avi Schiffmann’s belief that AI chatbots represent the future of online interaction, and the two may well be right.

Services such as Replika, Character.AI, and Friend have already demonstrated the popularity of AI companions, despite some users expressing concerns about growing bot integration on social media. Until recently, Character.AI allowed users to interact with fictional characters with remarkable success. The internet’s future could well shift towards explicit text-based role play, rather than today’s more implicit understanding that everyone adopts some form of online persona. If Meta takes an approach similar to other chatbot sites, social media might evolve from a place for human connection into an AI-powered fandom space.

Of course, several significant risks present themselves with this transformation. For one, there’s the obvious threat to business: AI profiles might fail like the Metaverse. If there is no future for cartoon versions of ourselves interacting in virtual reality, perhaps there is little hope for AI-generated Facebook friends and Instagram influencers. A more concerning risk is the fear that AI-generated interactions could overshadow human communication, creating an internet dominated by fiction. That said, a more intentional approach to fiction might be preferable to current debates around “post-truth” and “disinformation” — imagine a world where we engage with fake content knowing it’s fake!

There are also mental health considerations. Research, though limited, shows that vulnerable populations are made more susceptible to conditions like erotomania from online interactions, and this extends to chatbots. Some users are simply incapable of distinguishing between chatbots, scammers, and real people. There have also been several tragic cases in which minors with mental health conditions have died by suicide following long-term relationships with AI companions. While courts are still determining the extent of the chatbots’ role in these deaths, the long-term effects of AI dependence on both children and adults are worth investigating.

One potential response to AI saturation is a renaissance for human-centric media. Traditional — and, crucially, gatekept — media outlets such as the New York Times might experience renewed popularity when contrasted with the slop which otherwise dominates our feeds. Platforms such as Substack, which offer curated, paywalled environments, could become an “Etsy for words” in a world of mass-produced content and relationships. This could even benefit websites like OnlyFans, provided they maintain their focus on human creators — though it’s doubtful that the sex industry will emerge from the AI boom unscathed.

It’s not only the media space that has to grapple with the implications of AI. Consider the concept of “reality privilege,” introduced by venture capitalist Marc Andreessen. As Andreessen describes it, “reality privilege” refers to a society divided between people living in stimulating real-world environments and others who find more fulfillment online. This split became particularly clear last year, as Jonathan Haidt’s push to limit social media for teenagers earned wider popularity. That sounds like a great idea, until you think of someone who lives in Nowhere, Ohio, whose main connection to the real world comes through social media. A bifurcation like this risks deepening social inequalities, creating a world in which the privileged maintain access to physical experiences while others are left with the internet.

While social media in its current form has already challenged traditional notions of authenticity — encouraging users to curate and perform their lives — AI-generated “users” might take this to a new extreme, with entire communities built around knowingly fictional personas. Labelling these personas as AI — and therefore explicitly fictional — could, in some ways, be more honest. But what we are less prepared for is a world in which a substantial number of people knowingly choose fiction over reality.

Report this comment

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post

default_friend

default_friend