Microplastics and the Future of Water Risk

January 6, 2026

Marybeth Collins

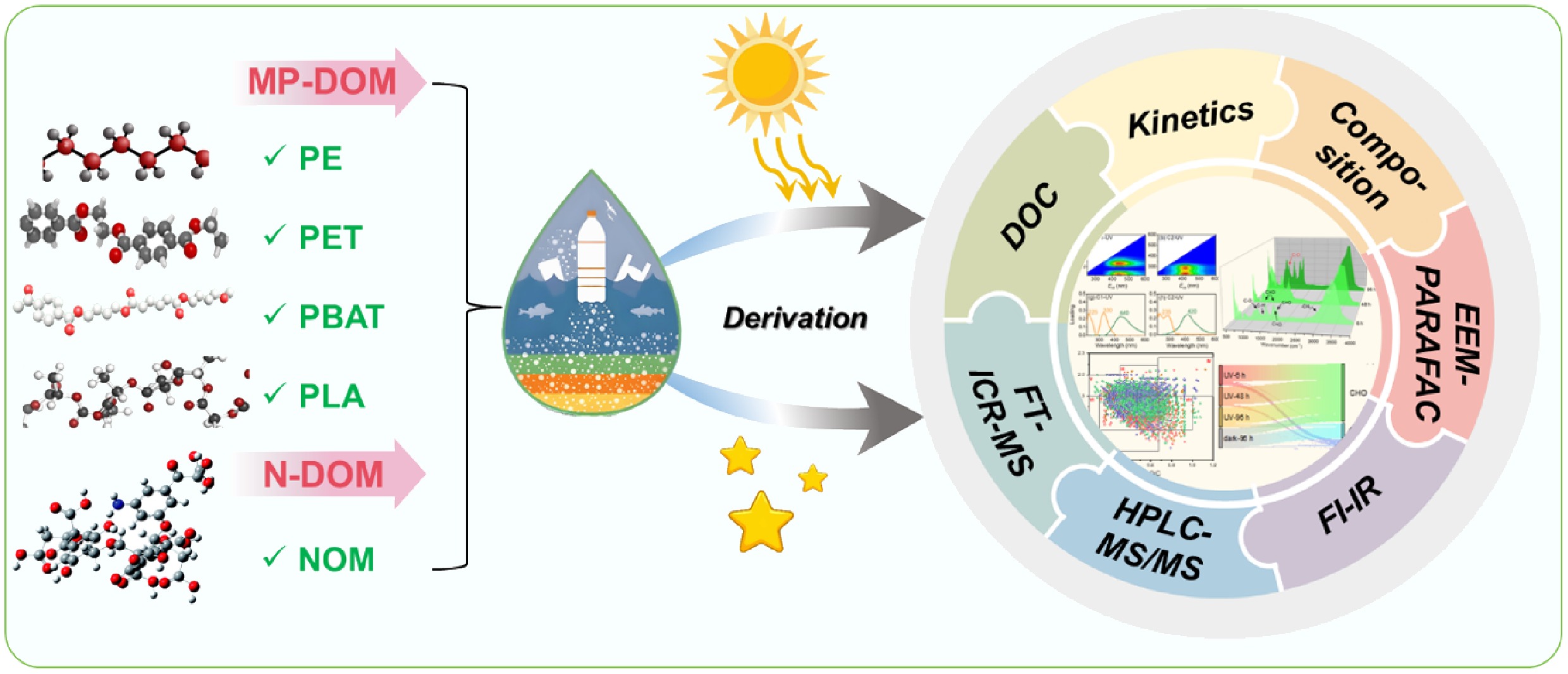

Microplastics have long been treated as a visible pollution problem—measured by particles, fragments, and fibers found in water bodies and treatment systems. That framing is rapidly becoming outdated. Emerging research shows that microplastics do not simply persist as particles; they continuously degrade and release microplastic-derived dissolved organic matter (MPs-DOM), subtly but materially altering water chemistry over time.

This shift—from physical contamination to chemical transformation—marks the beginning of a new phase of environmental risk management. One that existing water quality frameworks were not designed to address.

Why This Risk Is Emerging Now

Microplastics are now ubiquitous across surface waters, drinking water sources, and industrial systems. Their prolonged exposure to sunlight, heat, and operational stress accelerates chemical breakdown, releasing low-molecular-weight organic compounds into water. These compounds are not captured by traditional particle-based monitoring and are often indistinguishable from naturally occurring organic matter in standard tests.

The result is a growing class of “invisible” contamination—chemically active, continuously replenished, and largely unaccounted for in compliance and risk assessments. For organizations that depend on stable water quality, this represents a structural blind spot rather than a discrete environmental issue.

How Microplastics Are Changing Water Quality Dynamics

The environmental concern is no longer limited to the presence of plastic particles themselves. MPs-DOM behaves differently from natural dissolved organic matter in several critical ways:

- It is often more chemically reactive, increasing the likelihood of secondary reactions during treatment or disinfection.

- It can interact with metals and other co-contaminants, altering transport, toxicity, and removal behavior.

- It may be more bioavailable, influencing microbial activity and downstream ecological processes.

From a risk perspective, this means water systems can remain technically “in compliance” while underlying exposure pathways grow more complex and less predictable.

Why Existing Water Management Frameworks Fall Short

Most water quality regulations and operational standards are built around stable assumptions: identifiable contaminants, defined thresholds, and treatment systems designed for known inputs. MPs-DOM challenges those assumptions.

Current frameworks typically focus on particulate removal, total organic carbon, or specific regulated substances. They do not differentiate between natural organic matter and anthropogenic, plastic-derived compounds—nor do they account for continuous, UV-driven chemical transformation occurring after plastics enter water systems.

This creates a gap between regulatory compliance and actual risk control. Water quality may meet existing standards while still carrying emerging chemical exposures that are poorly understood and difficult to trace.

The Next Phase of Environmental Risk Management

This moment echoes earlier inflection points seen with PFAS, methane leakage, and indirect Scope 3 emissions. In each case, scientific understanding advanced faster than regulation, creating a window where early recognition—not formal mandates—defined leadership.

Forward-looking organizations are beginning to treat water quality as a dynamic system rather than a static compliance target. That means integrating emerging science into risk planning, monitoring indirect exposure pathways, and stress-testing assumptions about treatment performance and water sourcing.

The focus is shifting from reacting to regulated limits to anticipating how evolving definitions of water quality may affect operations, disclosures, and long-term costs.

What Leaders Should Be Watching

Several signals bear close attention: expanding research into microplastic-derived chemistry, increasing scrutiny of indirect contamination pathways, and growing expectations that companies demonstrate proactive water risk management—not just compliance.

As water stress, infrastructure aging, and chemical complexity converge, the definition of “acceptable” water quality is likely to evolve. Organizations that recognize this shift early will have more flexibility when regulatory, financial, and reputational expectations inevitably follow.

Microplastics in water are not simply another environmental metric. They signal a broader transition toward environmental risks that are less visible, more chemically complex, and harder to manage within traditional frameworks.

Environmental risk management is moving upstream—from monitoring outcomes to understanding transformation processes. Water quality sits at the center of that transition.

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post