Minnesota cannabis market leaves out small-scale entrepreneurs of color

October 29, 2025

When Minnesota legalized adult-use cannabis in August 2023, Alysha Bellamy was stoked. “Over the moon,” even. Now, more than two years later, Bellamy has doubts about whether the law will give small-scale entrepreneurs of color a fair chance to succeed.

The Minnesota Adult-Use Cannabis Act legalized the use, possession and cultivation of the plant. But the sale of marijuana wasn’t legalized until this June when licenses granting preliminary approval for cultivation, manufacturing and retail sales started to roll out to small and mid-sized businesses.

The law also expunged all past marijuana convictions, about 57,000 of them, as of May 2024, and a Cannabis Expungement Board was set up for reviewing cannabis records, a provision unique to Minnesota, says DFL Rep. Jessica Hanson who co-authored the bill. “There was no perfect method that would guarantee holistic repair and equity,” she said, but the process is continuing.

To make up for the fact that Black and brown communities were disproportionately affected by cannabis prohibition, the state promised to prioritize their startup businesses through a social equity licensing program. But entrepreneurs say the bureaucratic and financial barriers to starting a business are still daunting, and that well-established multistate operators have a head start in Minnesota’s new market.

In November 2024, social equity applicants sued the Office of Cannabis Management after it denied two-thirds of the applications. The plaintiffs claimed that OCM did not provide substantial reasons for rejecting their applications, while the OCM claimed that they were attempting to “flood the zone and place their thumb on the scale at the expense of legitimate social equity applicants,” OCM said in a press release. This halted the social equity license lottery that was scheduled for November 2024. In April, a judge ruled that OCM illegally cancelled the lottery and was obligated to hold it. OCM also agreed to give the plaintiffs priority in the upcoming license lotteries.

To qualify for a social equity license, an applicant must meet at least one criterion: having been convicted of a cannabis-related offense (or having a parent, spouse, guardian, or dependent who was); being a veteran or National Guard member, including those who were discharged due to a cannabis offense; having lived for the past five years in an area with high poverty, over-policing, or low median income; or operating a small farm.

Before legalization, enforcement of cannabis laws disproportionately affected Black and brown communities. Nationally, Black people are 3.6 times more likely to be arrested for marijuana than white people, despite similar usage levels, according to the American Civil Liberties Union. In Minnesota, Black people were found to be nearly five times more likely to be arrested on marijuana charges compared to white people.

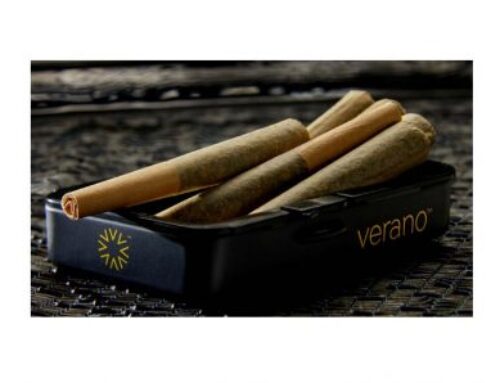

While the licenses started rolling out via lottery, big multi-state operators (MSOs) like Rise and Green Goods, the state’s licensed medical-use cannabis providers, were allowed to simply repurpose part of their inventory under a “combined business license” and enter the recreational-use market.

This left small-scale entrepreneurs of color feeling deceived. They say that as established businesses, Rise and Green Goods had an advantage of being able to start selling right away, while small-scale businesses, who have no inventory, funding, or retail space are having to scramble to get their business together.

Marcus Harcus was among those who advocated for the inclusion of the social equity provision in the bill. A lifelong cannabis consumer, a board trustee at the Minnesota Cannabis College and now a cannabis entrepreneur, Harcus also has a preliminary approval license and is hoping to secure an operating license for a brick and mortar retail store which needs $1.5 million in funding. He, too, is disappointed by how the law is being implemented.

“We were overrepresented in being criminalized, and will be probably underrepresented in having licenses and adequately capitalized businesses,” he said. “It’s sad that the state didn’t live up to this rhetoric about equitable craft cannabis.”

Bellamy, a chef and aspiring cannabis entrepreneur who is also a board member of the Minnesota Cannabis College, a nonprofit that prepares people to enter the market, had similar sentiments.

“Feels like it was misleading for the state to say that social equity got the leg up, but it was the MSOs who got the leg up,” she said. “I don’t see any social equity advantages.”

Bellamy, who holds a preliminary license, plans to expand her snack company, Munchie Crunchys, to include cannabis-infused products. She said securing funding to begin manufacturing has been difficult. Entrepreneurs with pre-approved licenses have 18 months to launch their businesses; four months have already passed.

Veronika Alfaro is the founder of Mi Sota Essence, which she says is the state’s first Latina-owned low-dose cannabis company, making Latino-inspired hemp-infused products like polvorones and agua frescas. Her husband, who was arrested at 18 for selling cannabis, now has preliminary approval for a small-scale social equity enterprise. “That [his arrest] completely changed our course of life. He wasn’t able to go to school, and wasn’t able to get a regular job,” she said.

While the law is meant to help those who were harmed by criminalization, it isn’t really helping those trying to start small-scale businesses, she said. The state issued cultivation and retail licenses at the same time. But, growing a commercial cannabis crop takes approximately 90 days, meaning these small-scale businesses might have licenses, but no legal product to sell for months.

“The market is just turning on without intentionality behind it. If it did, we would have growers first, transporters, manufacturers… retail would be our very last step.”

She is also the founder of the Minnesota Women’s Cannabis Collective, which works to support female-led cannabis businesses and provide resources and guidance to navigate the complex licensing rules, lack of financing and other challenges new entrepreneurs face.

After navigating the bureaucratic maze of the license application comes one of the toughest hurdles of the cannabis business: funding. With cannabis still illegal federally, banks often don’t provide loans for starting a business, even in a state where it is legal. Entrepreneurs like Harcus, Bellamy and Alfaro have to seek grants and venture capital or private funding to get their operations up and running.

Minnesota’s law established the Office of Cannabis Management to provide guidance, webinars and community outreach. It also introduced multiple grants, like CanGrow, CanRenew, CanStartUp, CanNavigate and CanTrain, for businesses at different stages of operation as well as those investing in communities that have been harmed by cannabis laws. Of these, the CanStartUp grant funds new cannabis microbusinesses with priority for social equity applicants. The grants can range from $2,500 to $75,000.

But, in the face of estimates of what it takes to get a business running, these grants can feel like little more than a drop in the bucket.

Bellamy estimates that opening a retail shop costs a minimum of $200,000, and that the investment can reach $3 million for an integrated operation that includes cultivation, manufacture and retail. “It’s almost like playing Frogger, like, where do I go? What should I do? How am I going to get this done?”

Even if they clear those hurdles, heavy regulation, high taxes, competition and barriers to funding make it hard to turn a profit. Only 27.3% of U.S. cannabis operators report being profitable, which is significantly lower than the 65.3% national average for non-cannabis small businesses, according to a 2024 study by Whitney Economics, which collects cannabis and hemp business data. The report also found that while 33.7% of white cannabis operators report profitability, only 17.5% of their non-white counterparts are profitable.

Jessica Jackson, the social equity director of the Office of Cannabis Management, acknowledges that the law is in its nascent stages, with potential flaws in execution. However, she said that entrepreneurs’ concerns stem from a “scarcity mindset because there’s limited capital.”

“Given the amount of opportunity that exists in Minnesota, I don’t think that it’s going to create a loss for our operators that are seeking to enter. I know that as our market matures, it’s not going to create the sort of the risk that they’re feeling right now in their early stage stress,” Jackson said.

“Cannabis legalization and our current social equity business policies were never going to — nor were they ever intended to — singlehandedly change this centuries-old status quo in a few short years nor mere months into market launch,” Hanson, the state legislator, said. Minnesota pushed the conversation farther than any other state, but there is more work to be done, she said.

But Harcus thinks it’ll be too late to make amends once the market is already up and running. “They’re creating this huge system, and it’s going to be full of flaws, and over time, a lot of those flaws can be corrected. The problem is, is it going to be too little, too late?”

“The reality is that this is still the beginning of a new industry, we’re building the infrastructure as we go, and it’s going to take time,” said Alfaro. “But it’s important for us to be part of the conversation now so we can help shape and build what comes next, together, and see ourselves reflected within it.”

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post