New Lehigh Valley group takes aim at Pa. road salt pollution problem

March 3, 2025

BETHLEHEM, Pa. — A new advocacy group, made up of volunteers from across Pennsylvania, are setting their sights on road salt.

“The goal of the working group is monthly meetings with volunteers with a statewide focus,” said Mary Rooney, president of the Little Lehigh Watershed Stewards.

“We’re going to develop goals, plans of action, how to meet those goals. And it’s time to get started.”

The group’s aim is to reduce salt pollution as well as promote responsible road salt application practices statewide.

And it’s an important aim — state data shows Lehigh County municipalities bought more rock salt than Philadelphia County did.

“A group like this to really dive into the details and understand the impacts on the water quality that kind of fall outside the drinking water regulations, is a great resource for us to protect the water supply for our customers.”Lehigh County Authority Chief Executive Officer Liesel Gross

The inaugural meeting of the PA Road Salt Action Working Group was held Tuesday.

The group is made up of just shy of two dozen residents, watershed stewards, conservationists and environmental advocates from across the commonwealth.

It’s run by Rooney and Jennifer Latzgo, the Little Lehigh Watershed Stewards’ education and engagement director.

The Lehigh Valley was well-represented at the meeting with Lehigh County Authority Chief Executive Officer Liesel Gross also in attendance.

“We are a public water and wastewater utility serving about 270,000 people in the city of Allentown and surrounding communities,” Gross said when introducing herself to the group.

“My interest is clearly in water quality and, specifically, protecting our drinking water sources for our customers.

“Since sodium and chlorides are not primary regulated contaminants per the federal and state standards for drinking water, a group like this to really dive into the details and understand the impacts on the water quality that kind of fall outside the drinking water regulations is a great resource for us to protect the water supply for our customers.”

Road salt impacts

Road salt generally is made up of sodium chloride, or rock salt, magnesium chloride or calcium chloride.

While those chemicals work to keep roads navigable during wintry weather by lowering the freezing point of water, chlorides can be persistent in the environment and wash into groundwater and build up over time.

In groundwater, chloride’s impacts can be far-reaching, including altering freshwater ecosystems and increasing the salt content in residential drinking water.

That’s on top of damage to built infrastructure, such as roads and bridges, as well as vehicle corrosion.

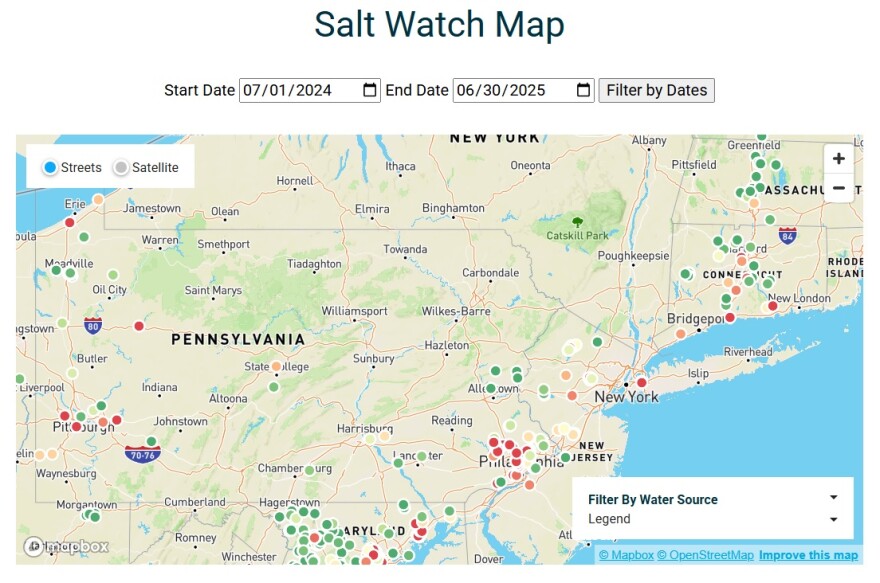

The Izaak Walton League of America, a century-old conservation organization, in 2018 launched its Salt Watch initiative through which residents across the United States can request a free salt testing kit to measure the level of chloride in local streams and waterways.

Screenshot

/

Izaak Walton League of America

“They’re doing a great job, but we didn’t see much in our watershed,” Rooney said during a recent interview with LehighValleyNews.com.

“So we decided to do ‘Salt Snapshots,’” a water-testing blitz over several hours at locations throughout a watershed.

The Little Lehigh Watershed Stewards in August 2023 tested water from 45 sites throughout the Little Lehigh Creek’s watershed.

The Little Lehigh flows from Topton in Longswamp Township, Berks County, through Lower Macungie and Salisbury townships, until it converges with the Lehigh River in Allentown.

It has a 181-square-mile watershed in Lehigh and Berks counties.

A trend uncovered

The analysis found a trend — increasing salt concentrations as streams flowed through more developed areas.

In those more developed areas, there are more impermeable surfaces, where de-icing products are more heavily used in winter.

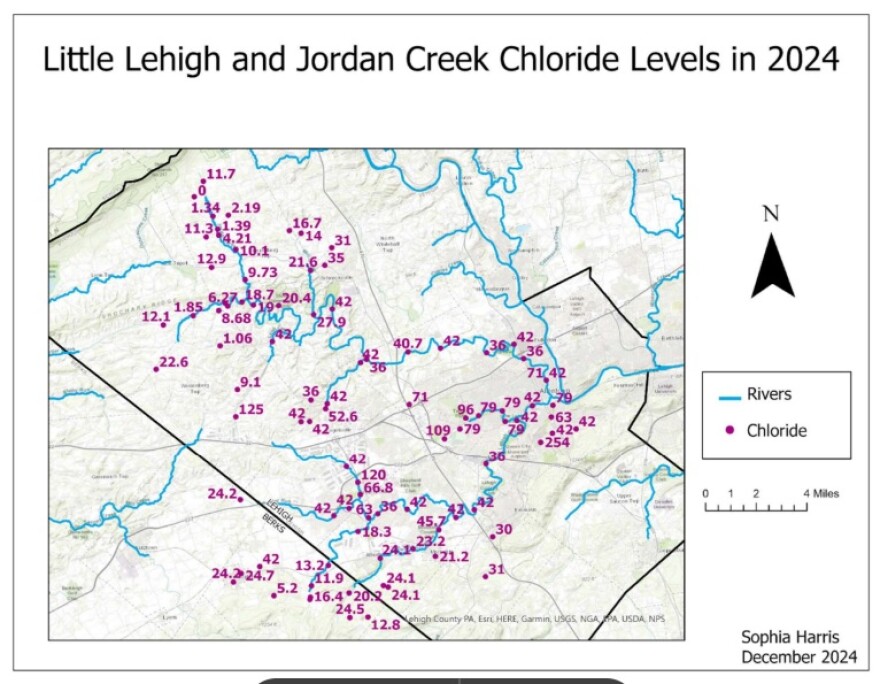

The following summer, the stewards were at it again, but expanded their testing area to include 45 additional sites in the Jordan Creek, which feeds into the Little Lehigh in Allentown.

The findings were similar — the more developed an area, the more concentrated chlorides are in water samples.

Screenshot

/

Little Lehigh Watershed Stewards

There are benchmarks to determine chloride toxicity in drinking water and freshwater streams.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has set a threshold of 230 mg/L, or milligrams per liter, of chloride to protect aquatic life in streams and 250 mg/L as the secondary drinking water standard for chloride.

However, scientists have found chloride levels at 50 mg/L to cause harm to aquatic life, including fish, amphibians and invertebrates.

Officials in Maryland, Ohio and Canada have set the threshold for long-term toxicity in streams much lower — at 50, 52 and 120 mg/L, respectively.

The Little Lehigh Watershed Stewards during last year’s testing found a range of chloride concentrations — from 0 mg/L near Blue Mountain to 254 mg/L in Allentown on Trout Creek.

“We’re going to do this testing again this summer, because three points of data, a trend of three years, is much more representative than just a point, or even two points,” Rooney said.

“So it’s our intent to repeat this one more time this summer.”

Sources of road salt

Road salt has several sources, including residents sprinkling it on front porch steps and driveways, private contractors clearing parking lots, and municipal and state workers clearing roadways.

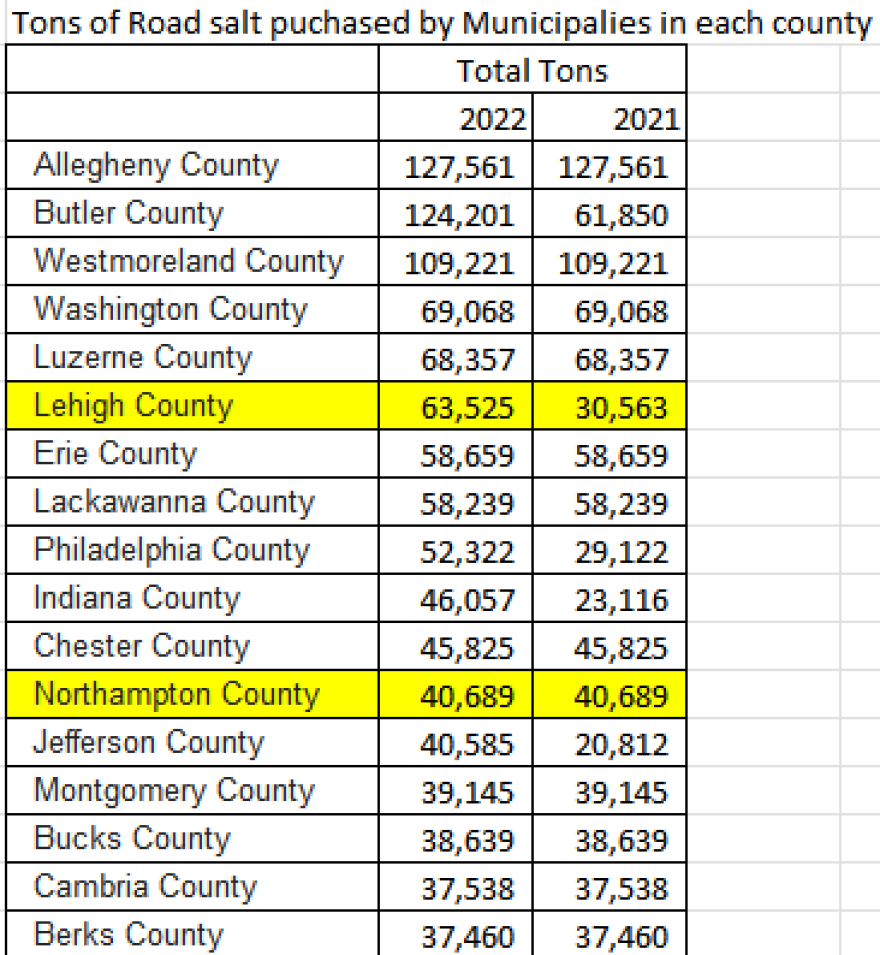

As research was underway on the ground in the Valley, Rooney submitted information requests to the state to find out how many tons of salt each county’s municipalities bought.

The state Department of General Services negotiates road salt prices on behalf of local governments.

The results were shocking, Rooney said.

In 2022, the most recent year for which data is available, Lehigh County ranked sixth of Pennsylvania’s 67 counties for most tons of rock salt bought by municipalities, at more than 63,500 tons.

Northampton County ranked 14th, buying more than 40,600 tons.

Screenshot

/

Little Lehigh Watershed Stewards

That year, Lehigh County municipalities bought more rock salt than Philadelphia County did.

“People can say it’s all over the county, but the problem isn’t that it’s all over the county,” Rooney said.

“It’s that, when the salt is put on the roads, it washes into the creeks and it washes into our groundwater. It doesn’t disappear.”

‘Don’t willy-nilly just go out there’

With back-to-back storms this winter causing some municipalities to run low on road salt, advocates are targeting local officials with information campaigns and reaching out to Environmental Advisory Councils, too.

Rooney recently gave a presentation on the impacts of salt pollution during an Allentown EAC meeting.

“None of us are saying, ‘Don’t use salt,’” Rooney said. “We’re saying, ‘Use the right amount of salt in the right place at the right time to get the safety results.

“But don’t willy-nilly just go out there.”

Some best practices include using a brine in lieu or rock salt, or wetting the salt before spreading so it doesn’t bounce off surfaces.

Proper planning, training and equipment calibration — before winter weather comes — also can dramatically lessen the amount of rock salt spread in the first place.

To bring municipal workers and private contractors together, Rooney also wants to host a “Snow Rodeo,” she said.

“The idea is you get a bunch of people from municipalities or contractors together in some parking lot in October,” she said.

“You give the people salt training. You have them bring some of their equipment in there. You teach them how to calibrate the equipment.

“And then, supposedly, the rodeo idea is to make it fun — you set up some obstacles and you have the guys show their skills.”

‘More than is needed’

But residents also need to change their perception of how much salt is enough, she said.

“We have to educate the person who’s walking on the sidewalk and only feels comfortable walking on the sidewalk when there’s that crunch,” Rooney said.

“Because people’s perception now is so skewed toward over-salting that when they see a proper amount of salt application, they think people aren’t doing anything.”

“Our group is not against road salt. What we have found is that the amount of salt that’s being put on the roadways is excessive.”Mary Rooney, president of the Little Lehigh Watershed Stewards

Part of the work is in building relationships with officials, contractors and residents to engage them in best practices, Rooney said.

“We’re doing this in a very let’s-be-allies-and-work-against-this-problem way,” Rooney said. “We’re not trying to point fingers.

“Those guys out there and those women out there who are out trying to keep our roads safe — we’re all for that. Our group is not against road salt.

“What we have found is that the amount of salt that’s being put on the roadways is excessive. It’s more than is needed to allow the roads and the sidewalks to be safe.”

‘That’s the goal’

Last month, the Little Lehigh Watershed Stewards held a Conversation Cafe about road salt and its impacts.

Hosted by the Pennsylvania Organization for Watersheds and Rivers, or POWR, that event preceded the working group that met Tuesday afternoon.

The meeting started off with two main ideas, Rooney explained to the group.

First, that there would be a statewide working group with members organizing the actions needed to be taken in order to reduce road salt usage.

The second is to bring together a statewide network of advocacy partners.

“Those are the people who are working in their groups locally, watershed groups, master watershed stewards working in their area.

“All your environmental organizations, you know, the conservation districts, any of those can be advocacy partners … So it’s to kind of coordinate those two efforts — that’s the goal.”

In addition to residents, there were representatives from organizations across the commonwealth, such as the Mercer County Conservation District, the Susquehanna River Basin Commission and Penn State Extension’s Master Watershed Steward Program, among others.

‘We have a lot of experience here’

Kevin Roth, director of education, outreach and volunteering at the Pennypack Ecological Restoration Trust in Huntingdon Valley, Montgomery and Bucks counties, said the group was fulfilling a need to bolster outreach efforts.

“We’ve been involved in Salt Watch since about 2018, when we noticed our sensors were going up, not when the township salted, but when all the local strip malls salted,” Roth said.

“That’s when we kind of realized that’s where the problem was coming from around here, and how do we educate people and do better about that?

“But we want to do more. Now that people know about it, we need regulations. We need to do better. So a group like this is just what we need.”

During the almost two-hour virtual meeting, Rooney went over possible goals for the year, including creating a website with resources for advocacy partners and a public education campaign.

Also, targeted efforts to support legislation, training and possible grants for equipment upgrades.

Participants were asked to join different teams depending on experience and interest, such as for the website, training, legislation and grant funding.

“One of the hopes is that when we get this many heads together, we have a lot of experience here and a lot of knowledge,” Latzgo said.

The group’s next meeting, while not yet scheduled, is earmarked for late March or early April.

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post