‘People are wrestling with the burden’: Japan pivots to focus on nuclear power ‘maximisati

December 30, 2025

-

Japan’s vital statistics

-

GDP per capita per annum: $34,700 (global average $14,210)

-

Total annual tonnes CO2: 961m

-

CO2 per capita: 7.77 metric tonnes (global average 4.7)

-

Most recent NDC (carbon plan): 2025

-

Climate plans: critically insufficient

-

Population: 124 million

The stillness of a bitterly cold afternoon is broken by the swish, swoosh of three 50m-long blades, adjusting automatically to the tiniest shift in the direction of a dependable westerly wind that keeps them turning day and night.

From here, up on a mountain ridge in rural Fukushima prefecture in north-east Japan, the wind turbines stretch for miles. In the distance, you can see the outlines of the reactor buildings at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant, which is in the slow process of being decommissioned at a cost so far of $35bn (£26bn) almost 15 years since it suffered a triple meltdown after being struck by a magnitude-9.0 earthquake and a 15m (49ft) tsunami. Another nuclear plant further south stands idle.

But the 46 turbines that make up the sprawling Abukuma windfarm – the biggest onshore windfarm in Japan – could offer hope for a different future for the region’s energy supply. Built at a cost of ¥67bn (£310m), the facility went into full operation in April this year, weeks after Japan’s government previewed its strategic energy plan as it aims to achieve net zero by 2050.

The plan has been controversial with campaigners because it ditches attempts to reduce Japan’s reliance on nuclear power after the Fukushima disaster, calling instead for a “maximisation” of nuclear power, which will account for about 20% of total energy output in 2040: about 14 reactors have been restarted and the assumption is that 30 will be in full operation by then.

The post-Fukushima nuclear closures of dozens of reactors forced the country to rely heavily on imported fossil fuels: last year it was the world’s second-largest importer of liquefied fossil gas after China, and the third-largest importer of coal by volume. But the government’s energy plan envisages a share of between 40% and 50% for renewable energy – compared with just under a third in 2023 – and a reduction in coal-fired power from the current 63% to 30-40%.

Fukushima plans to become a leader in renewable energy – a shift that would have elicited derision before tsunami waves roared ashore on the afternoon of 11 March 2011, crippling the Daiichi plant’s backup power supply and triggering the world’s worst nuclear accident since Chornobyl a quarter of a century earlier. In its Renewable Energy Promotion Vision, the prefecture, home to 1.7 million people, aims to achieve 100% renewables by 2040, with a midterm target of 70% by 2030.

“Everyone in the prefecture is determined to reach the target,” said Takayuki Hirano of Fukushima Fukko Furyoku (Fukushima Wind Power Recovery), a joint venture funded by nine companies and led by Sumitomo Corporation. “That’s why there are so many subsidies available for solar, wind and other renewables. I think we’re going to make it happen.

“People have negative memories of nuclear power and Fukushima, and they’re still wrestling with that burden.” The wrecked atomic plant generated power for business, industry and homes in Tokyo, 150 miles to the south. Fifteen years on, some of the 160,000 people who were evacuated have returned home after atmospheric radiation levels were declared safe; but levels in other communities are still too high for people to go back permanently.

By contrast, a portion of the power produced by Abukuma’s turbines is consumed locally, including by a mackerel aquaculture project and a town hall, via feed in premiums, under which electricity is sold on the wholesale power market or directly to individual consumers. “It is about local production for local consumption,” Hirano said.

As the world’s fifth biggest emitter of greenhouse gases, Japan has had some success in reducing its carbon footprint. Emissions fell by 4% to a record low in the year to the end of March 2024, led by lower energy consumption as well as the increased use of renewable energy and the restart of nuclear power plants. It aims to reduce emissions by 46% from 2013 levels by 2030.

But the widespread post-Fukushima shutdown of Japan’s nuclear reactors – and the politically fraught process of restarting them – have made the country more fossil-fuel friendly than other comparable economies. At Cop30, Japan again received the Fossil of the Day award from the Climate Action Network, a global network of NGOs, for its slow progress in decarbonising. As Japan complained that it had been unfairly singled out while bigger CO2 emitters, notably China, had been overlooked, the network said it had selected the country for its promotion of carbon capture and storage, which it claimed were measures “dressed up as solutions”.

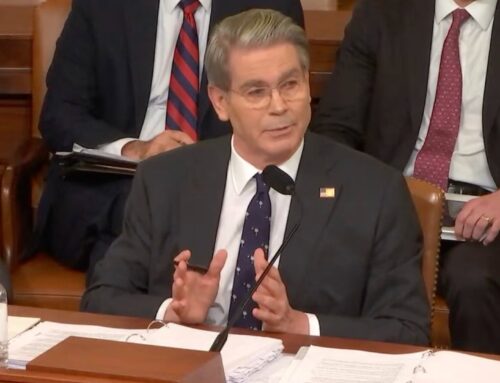

As the summit neared its end, Japan’s environment minister, Hirotaka Ishihara, drew condemnation from campaigners after he indicated that Tokyo would not sign up to Brazilian president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s proposed roadmap to transition away from fossil fuels, putting it at odds with about 80 other countries attending the summit in Belem.

Ishihara “has sent the wrong signal by refusing to support global efforts to accelerate a just transition from fossil energy to 100% renewables in order to achieve the Paris Agreement’s 1.5C goal”, said Masayoshi Iyoda, a campaigner at 350.org, an environmental group campaigning for a global transition from fossil fuels to renewables.

Japan’s new prime minister, Sanae Takaichi, “must realise that energy efficiency and renewable energy represent the fastest path toward 100% energy self-sufficiency”, Iyoda added. “Supporting the fossil fuel phaseout roadmap will not jeopardise, but advance, Japan’s interests by paving the way to a resilient and sustainable economy.”

Hirano said the Abukuma venture was “our way of helping Fukushima recover so that one day people around the world will automatically associate it with renewable energy and not nuclear power”.

But geothermal energy will play a role too. Further inland, Tomio Sakuma, the renewable energy area manager for Genki Up Tsuchiyu, the company that operates the geothermal plant, opens a valve to unleash a fierce spray of steam whose origins lie deep below ground. Here, in the hot spring resort of Tsuchiyu Onsen, local authorities are drawing on Japan’s geological characteristics to rewrite Fukushima’s energy story.

It is hard to think of a better location. In most of Japan’s 3,000-plus onsen, or hot spring resorts, businesses must dig individual wells to secure a supply of hot water. Here, however, the town’s economic life force comes from a single source, making it easier for the plant to harness subterranean steam to drive a turbine, before it is combined with cold mountain water to make it suitable for bathing.

Sakuma said: “The good thing about this project is that we don’t recycle water and send it on to the bath houses and inns as an afterthought. It’s a more natural, linear process.” The town hosts a stream of people from other onsen towns hoping to emulate their success, he added.

The plant would not be out of place in a steampunk novel – a cluster of pipes, tubes, gauges, and valves that together generate 440kW of electricity; enough to power about 800 homes and provide water for a nearby aquaculture facility. Earnings from feed-in tariff sales are then used to fund Tsuchiyu Onsen’s continuing recovery from the 2011 earthquake and build new ryokan inns to accommodate visitors, including a growing number of foreign tourists.

Fukushima, meanwhile, is on course to reach its goal. Renewables, led by solar panel facilities that cover areas once occupied by families displaced by the triple meltdown, account for almost 60% of the prefecture’s power generation, compared with just 23% at the time of the 2011 disaster.

Takayuki Kato, the chief executive of Genki Up Tsuchiyu, said: “We are an important part of Fukushima’s 100% renewable energy target.” Tsuchiyu’s own deadline was five years earlier than the prefectural government’s, he added. “If we don’t set and then reach an ambitious target, we can hardly claim to be a symbol of Fukushima’s energy transformation.”

-

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post