Plants struggled for millions of years after Earth’s worst climate catastrophe

March 6, 2025

With the world on the threshold of 1.5°C of warming, one pressing question is: how bad can it get? The answer may lie beneath our feet.

Buried underground are rocks, many rocks, and they are old. For palaeontologists like us, they are a vast archive of past life on Earth. In particular, they can tell us how life on land fared during times when the climate warmed suddenly. Our new study showed that plants were severely affected and forests took millions of years to recover.

About 252 million years ago more than 80% of marine species became extinct. This is known as the end-Permian mass extinction, arguably the most significant climatic crisis since the earliest appearance of animals, more than 555 million years ago. It seems that the prime culprit was the massive amount of warming-inducing greenhouse gas released by volcanoes in a region known as the Siberian Traps in Russia.

Marcos Amores

Evidence suggests that plants may not have suffered a mass extinction, but their communities were heavily affected, if not destroyed outright. While the extreme heat would have pushed plants and animals past their tolerance limits, they probably also faced deadly droughts, ozone depletion, widespread wildfires and toxic heavy metal contamination.

Data on how plants fared following the end-Permian extinction are plentiful, but little is known about those located at higher latitudes, where it was cooler. Thriving ecosystems existed at polar latitudes back then, aided by a mostly ice-free polar region. At the end-Permian event, however, this ecosystem was entirely wiped out.

Our work examined the rocks and fossils of the Sydney region of Australia, which was located near the south pole for at least 8 million years following the worst mass extinction in Earth’s history. These well-preserved, long-term records provide a window into the recovery of plant communities furthest away from the source of trouble.

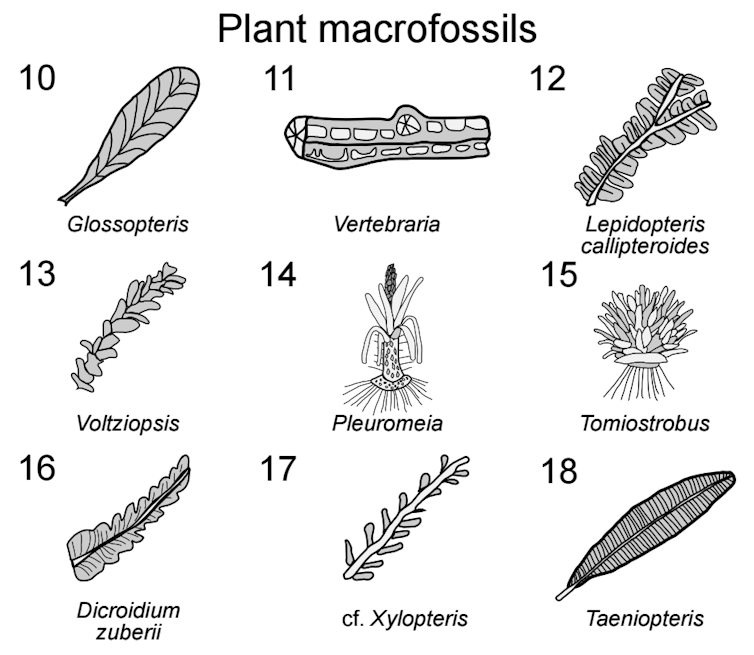

The plant fossils from these Australian rocks showed that conifers, like modern pines or cypresses, were some of the earliest to colonise the land immediately following the calamity. The recovery to flourishing forests, however, was not smooth sailing.

We discovered that even higher temperatures 2 million years after the end-Permian event caused the collapse of these conifer survivors. In turn, they were replaced by tough, shrubby plants resembling modern clubmosses (like Isoetes). How hot it got in Sydney is not known, but this scorching period lasted for about 700,000 years and made life challenging for trees and other large plants.

Amores et al. 2025, GSA Bulletin

When cooling conditions finally manifested, large but unusual plants that looked like ferns but bore seeds like conifers flourished and established more stable forests in Sydney. This recovery took less than 100,000 years to happen. These plants eventually dominated the landscape for millions of years, paving the way for the lush forests during the Mesozoic age of the dinosaurs.

So, after million of years, the forest ecosystems of the Mesozoic came to look like those from before the end-Permian event. But crucially, the plant species that made up the new forests were completely different.

The term “recovery” can be misleading. Forests recover eventually, but extinction of individual species is forever.

By understanding how ancient plant ecosystems weathered extreme climate swings, we, as researchers, hope to learn valuable lessons about how modern plants and ecosystems might cope (or not) with today’s climate crisis. With this knowledge, we can inform policymakers of what is yet to come, and help steer a course that will avoid the worst climate outcomes over the longest possible timeframes.

So, fossil records add a data-driven long-term perspective to the climate choices we make today. Ecosystems depend on a fragile balance, with plants as the backbone of food webs on land and climate regulators.

The fossils have spoken: the disruption of these systems can have consequences that last hundreds of thousands of years, so protecting today’s ecosystems is more important than ever.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 40,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post