Population explosions and declines are related to the stability of the economy and the env

May 12, 2025

For 200 years, we’ve been warned of unchecked population growth and how it leads to environmental instability. On the other hand, today some countries face decreasing populations, alongside increasing proportions of elderly people, causing economic instability.

These two facets of population crises — explosions and declines — are occurring in different parts of the world, and have a global impact on the environment and on economies. Discussions about achieving economic and environmental sustainability must consider population changes, technology and the environment, given these concepts are closely interwoven.

Population explosions and declines are related to both environmental and economic instability; some countries make reactionary choices that trade off short-term domestic economic progress over the environment.

The crisis of population explosions

In 1798, English economist Thomas Malthus warned of a population explosion, inferring that population growth will outstrip agricultural production. Malthus’s ideas became re-popularized by American scientist Paul R. Ehrlich in his book published at the height of population growth in the 1960s. Both predicted that a population explosion would cause shortages in resources and escalating environmental damage.

Like Malthus, Ehrlich was criticized for a crisis “that never happened” because human ingenuity, a byproduct of population, overcomes the worst fears of environmentalists. This counter-argument relies on technological advances making more efficient use of resources while lowering the environmental impacts.

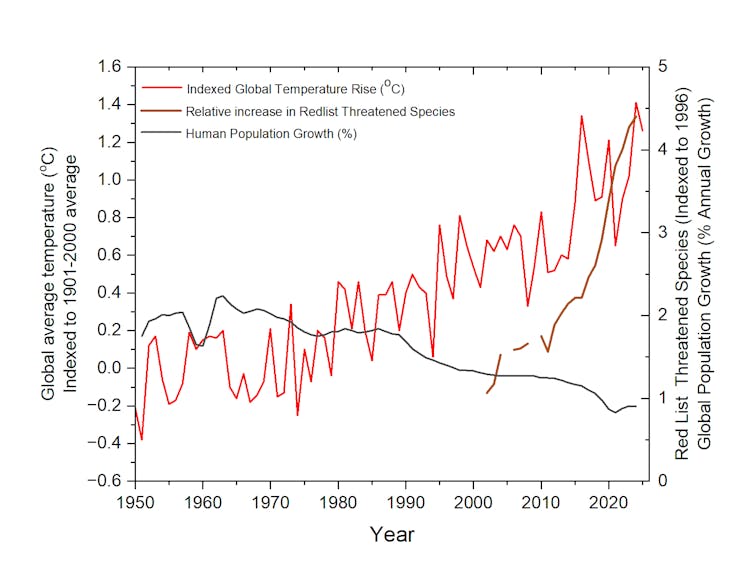

This is best exemplified by efficiency gains of agriculture that have continued to feed a growing world. Ehrlich’s predictions of cumulative environmental damage are best illustrated by the growing intensity of climate change and species loss as the global population continues to grow even though the current growth rate is slower than it was in the 1960s.

(K. Drouillard), CC BY

Unified growth theory describes how economies change over the long term. It starts with a period of slow technological progress, low income growth and high population growth. Over time, these conditions give way to a modern growth phase, where technology improves quickly, income rises steadily and population growth slows as societies go through a demographic transition towards stable population sizes.

Technological progress positively contributes to national economies over the long term. However, early adoption of green technology often relies on finance and government incentives that may imply short-term economic burdens. Yet when green technology is implemented and coupled to slowing population growth, it leads to decreasing national environmental footprints that pave a way towards joint environmental and economic sustainability.

The crisis of population declines

Declining populations cause inverted age pyramids with larger numbers of elderly people. These shifting demographics cause economic instability. They also constrain technological progress and social security.

Population declines work against the gains described by unified growth theory. Presently, 63 countries have reached their peak population and 48 more are expected to peak within 30 years. Fears of population decline are also being forecast at the global scale.

The global population is predicted to peak between the mid-2060s to 2100, stabilizing at 10.2 billion from its present 8.2 billion.

In their book, Empty Planet, political scientist Darrell Bricker and political commentator John Ibbitson warn that zero population growth will happen even faster. They argue once a country decreases its fertility to below replacement (2.1 children per woman), the social reinforcements of increasing urbanization, costs of raising children and increased empowerment over family planning make it almost impossible to increase the birth rate.

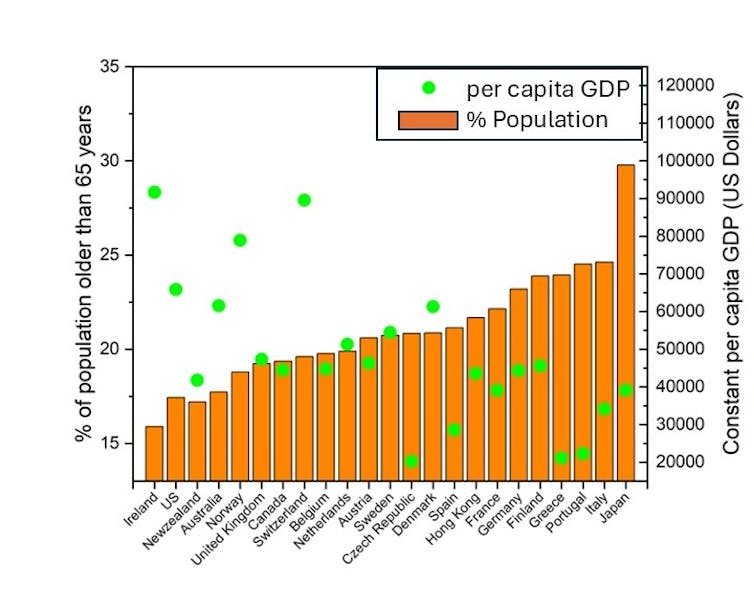

For highly affluent countries, the per capita GDP is decreasing as the proportion of elderly in the population increases. Although this pattern doesn’t hold when less affluent countries are added, the figure demonstrates tangible economic impacts for countries grappling with aging populations.

(K. Drouillard), CC BY

Simultaneous explosions and declines

Affluent nations facing decline can react to economic instability in ways that counter global economic and environmental sustainability.

In the past, affluent nations were the drivers of green technology. However, economic instability from population declines can cause reluctance to invest, adopt and share green technology crucial for mitigating environmental damage at the global scale.

The issue is compounded by the fact that many countries overlook how their own decline in population growth contributes to economic instability. They instead focus on short-term solutions to their economic situation that may include unsustainable resource use.

Left unaddressed, the real issue of population decline becomes unresolved, allowing social anxieties against immigration and global trade to grow. This can exacerbate the issue halting technology sharing, slowing economic growth and increasing economic inequality and environmental damage.

The above is exemplified by policies now being implemented by the United States. Where immigration was previously used as a backstop against low fertility, growing cultural backlash to immigration pressures rooted in anxiety about economic uncertainties have generated new policies causing the deportation of millions of immigrants and closing borders. This will most likely accelerate a population decline in the U.S., as highlighted by a Congressional Budget Office report.

At the same time, the U.S. is shifting its energy policy away from increased shares of renewable, green energy sources back to a focus on fossil fuels that will worsen climate damage.

Climate damage costs are currently two per cent of global GDP, and may increase to between two to 21 per cent of some countries’ incomes by the end of the century. The growing applications of artificial intelligence (AI) and its high energy use will add to climate damage. AI may also contribute to the economic challenges related to population decline if it replaces, rather than supports, labour.

Finally, tariff wars add new barriers against green technology sharing.

THE CANADIAN PRESS/Ethan Cairns

Canada’s lowered immigration

Canada, which already has a low fertility rate and is reacting to the U.S. trade war, has its own challenges. This year, immigration targets were decreased by 19 per cent. The lack of support for and subsequent removal of the carbon tax and possible extension of pipeline infrastructure could generate similar delays in the transition away from fossil fuels.

Read more:

Who really killed Canada’s carbon tax? Friends and foes alike

In the most recent federal election, discussions about environmental policy were largely side-tracked by economic issues.

Our research indicates that Canada and other affluent nations need to establish longer-term solutions to economic instabilities that mitigate environmental damage while promoting sustainable national and global economies.

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals offer pathways for economic, social and environmental sustainability. However, realizing these goals requires society to fully acknowledge the intertwined relationships between population growth, economy, environment and international technology-sharing in ways that transcend short-term national interests and reactionary policies.

The past decade has seen strong momentum from social and natural sciences as well as international organizations, business and civil society. Unfortunately, the current climate of economic uncertainty is halting this progress — unless the public can force broader discussions about sustainable approaches back into the political sphere.

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post