Puerto Rico in the Dark: Unraveling the Island’s Energy Crisis

January 1, 2025

Why Can’t Puerto Rico Keep the Lights On?

TL;DR:

-

Puerto Rico’s Energy Crisis: Puerto Rico’s ongoing struggle to maintain a stable power supply stems from historical neglect, financial mismanagement, and its vulnerability to natural disasters. Hurricanes Maria (2017) and Fiona (2022) exposed the fragile and outdated grid infrastructure, which has not been fully rebuilt or modernized. Systemic issues like underinvestment, corruption, and bureaucratic inefficiencies exacerbate the challenges, leaving residents and businesses grappling with frequent blackouts and economic disruptions.

-

Historical and Structural Challenges: PREPA’s shift from hydroelectric to fossil fuels in the mid-20th century, coupled with deferred maintenance during economic downturns, laid the groundwork for today’s unreliable grid. Centralized energy generation has left the system vulnerable to widespread outages during natural disasters. Privatization efforts with LUMA Energy (2021) and Genera PR (2023) have yet to deliver on promises of modernization and improved reliability, further fueling public frustration.

-

Natural Disasters and Recovery: Hurricanes Maria and Fiona devastated the power grid, highlighting its lack of resilience. Federal funds for recovery have been delayed by bureaucratic red tape and controversies, such as mismanagement and corruption in contracting. Recovery has been slow, with critical projects incomplete, leaving the grid susceptible to future storms.

-

Energy Policy and Privatization: The 2019 Energy Public Policy Act set ambitious renewable energy targets, but implementation has been hindered by economic and political challenges. The transition to natural gas, championed by recent administrations, aims to stabilize the grid but raises environmental and dependency concerns. Privatization has sparked mixed reactions, with criticism over increased costs and continued outages.

-

Social and Economic Impact: Persistent power outages disrupt daily life, healthcare, and business operations, stifling economic growth and deterring investment. Tourism, a key economic sector, suffers from the island’s unreliable energy infrastructure. The Jones Act further inflates energy costs, limiting Puerto Rico’s ability to source affordable fuel and materials.

-

Future Outlook: Puerto Rico faces significant hurdles in achieving energy reliability and resilience. A long-term strategy integrating renewable energy, modernizing the grid, and addressing governance inefficiencies is critical. Without comprehensive reforms and investment, the island’s energy crisis will continue to undermine economic stability and quality of life. However, leveraging solar energy and community-driven solutions offers hope for sustainable progress.

And now for the Deep Dive…

Introduction

Puerto Rico’s struggle with maintaining a reliable power supply is a complex issue that has persisted for decades, becoming particularly evident after catastrophic natural events like Hurricane Maria in 2017 and Hurricane Fiona in 2022. These events not only showcased the vulnerability of the island’s electrical infrastructure but also highlighted systemic problems that have been brewing for years. Understanding why Puerto Rico cannot keep the lights on involves delving into a mix of historical, economic, political, and environmental factors that have collectively contributed to this ongoing crisis.

The inability of Puerto Rico to keep the lights on consistently is rooted in a combination of historical underinvestment, the financial distress of PREPA, natural disasters’ devastating impacts, complex energy policy decisions, the economic strain from laws like the Jones Act, and the challenges of transitioning to a more sustainable and resilient energy system. Addressing these issues requires not just immediate repairs but a long-term strategy that involves robust policy reforms, significant investment in modernizing the grid, fostering local renewable energy solutions, and perhaps reconsidering the implications of colonial policies that affect Puerto Rico’s autonomy in managing its own resources and infrastructure. Only through these comprehensive approaches can there be hope for a stable and reliable energy future for the island.

Historical Context of Puerto Rico’s Energy Infrastructure

The historical context of Puerto Rico’s energy infrastructure provides insight into the current state of its electrical system. In the early days, the need for a comprehensive energy strategy was recognized with the establishment of the Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority (PREPA) in 1941. This public corporation was created to manage the island’s electric needs at a time when Puerto Rico was undergoing significant industrial and urban development. PREPA’s inception was part of broader economic development plans to transition Puerto Rico from an agricultural to an industrialized economy, which required a stable and expanding source of energy.

Initially, PREPA focused on harnessing the island’s natural resources, starting with hydroelectric power. Puerto Rico’s mountainous terrain provided several opportunities for dam construction, which could generate electricity through the force of water. Notable projects included the Guajataca and Carraízo dams, which not only served electricity needs but also provided water for irrigation and consumption. This reliance on hydroelectricity was seen as a sustainable approach for the time, but as demand for electricity grew with population and industrial expansion, it became clear that water alone would not suffice.

(Pictured above: The Carraízo Dam)

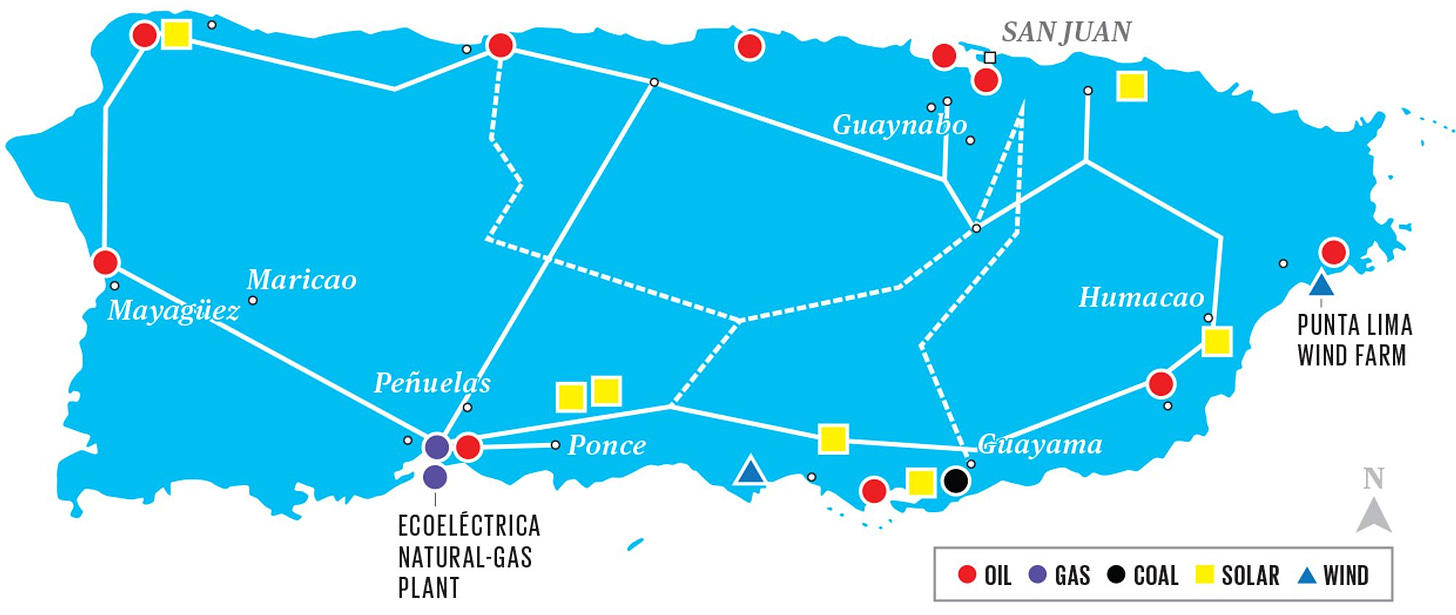

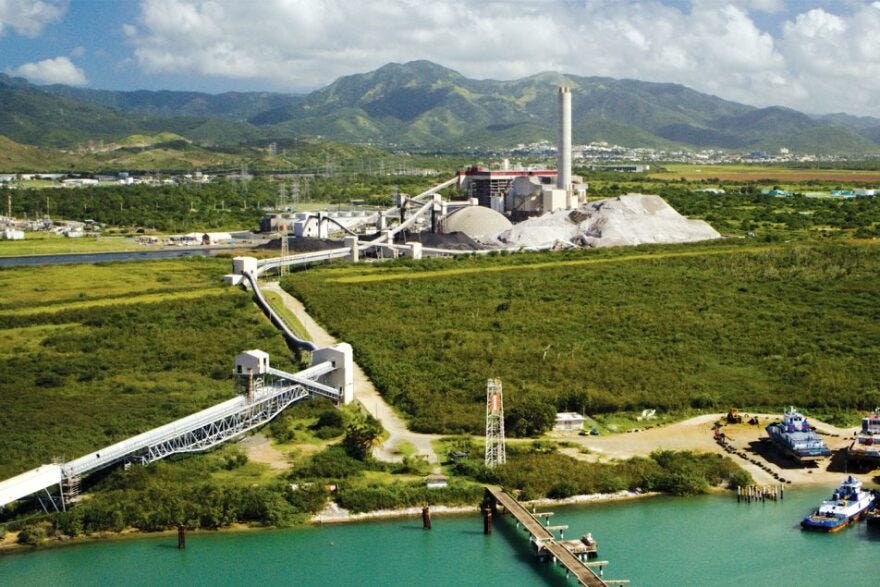

As a result, PREPA began to diversify its energy sources, turning to fossil fuels like oil in the 1960s. This shift was largely necessitated by the island’s geographical constraints. There are no significant local sources of fossil fuels, making Puerto Rico dependent on imports. The switch to oil was also influenced by the global oil boom, which made oil relatively cheap and abundant, although this would later become a double-edged sword as prices fluctuated. Coal was introduced later in the mix, particularly with the construction of plants like the one in Guayama, further deepening the reliance on non-renewable energy sources.

(Pictured above: AES’ Guayama plant in Puerto Rico surrounded by large piles of coal byproduct)

The economic fabric of Puerto Rico began to fray in the 2000s, marking the onset of a decline that would impact the maintenance and modernization of its energy infrastructure. The island’s economy was hit hard by several factors including the loss of tax incentives for U.S. corporations, increased competition from global manufacturing, and a overall economic recession. This downturn meant less revenue for the government, which in turn affected PREPA’s funding. Maintenance of the aging infrastructure was deferred, leading to more frequent breakdowns and inefficiencies in power generation and distribution.

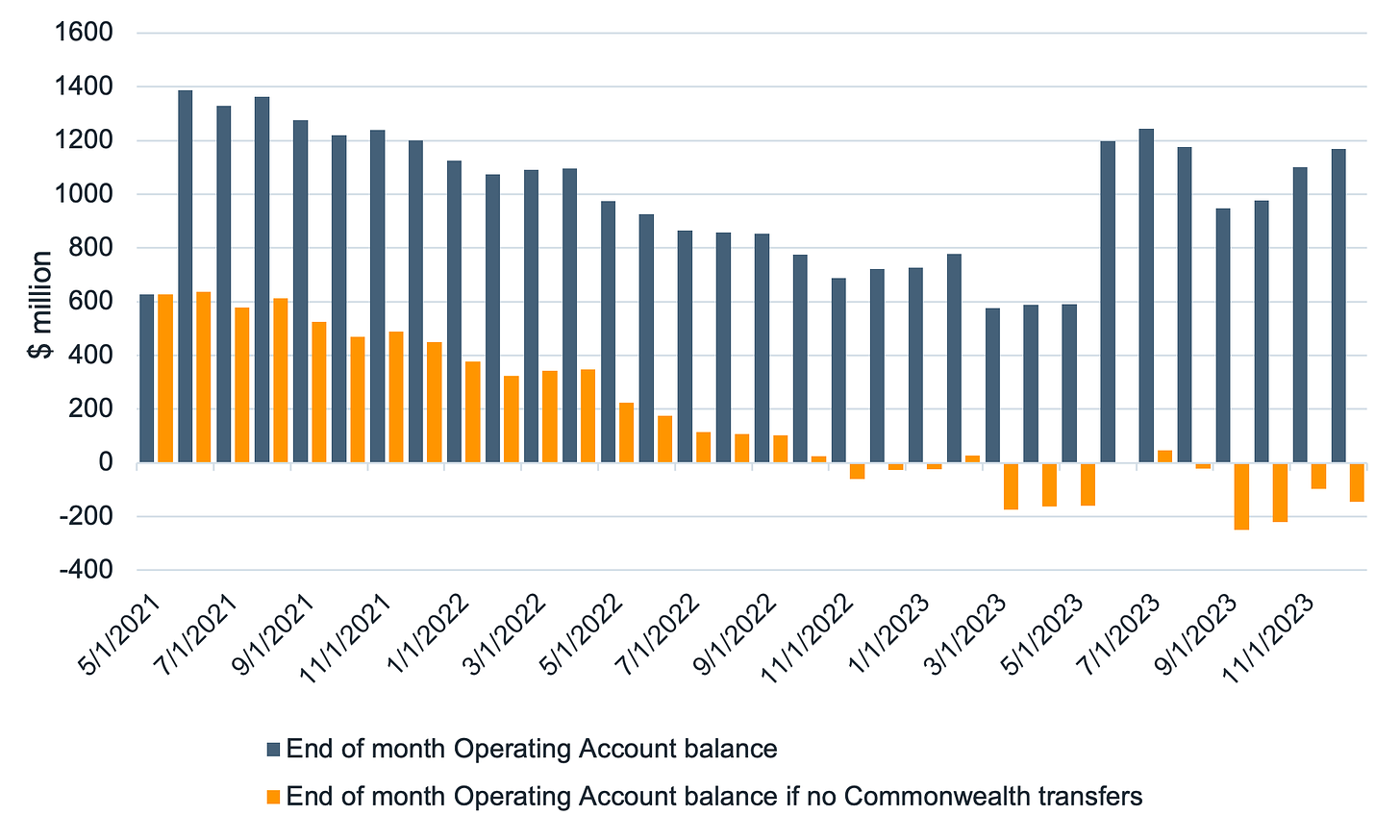

During this period, PREPA’s financial struggles became increasingly evident. The utility was sinking under the weight of debt accrued from loans taken to expand and maintain the grid, alongside operational costs that were not balanced by sufficient income. The economic downturn led to reduced electricity sales, while at the same time, the cost of fuel imports rose due to global price volatility. This combination of factors led to PREPA accumulating over $9 billion in debt by 2017, with much of it being bond debt that was supposed to fund infrastructure improvements but instead went towards operational cost management.

The culmination of these financial issues led to PREPA’s historic bankruptcy filing in 2017 under Title III of the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act (PROMESA). This was the largest municipal bankruptcy in U.S. history at the time, highlighting not just PREPA’s fiscal distress but also the broader systemic economic challenges facing Puerto Rico. The bankruptcy filing was a critical moment that underscored the need for a complete overhaul of how energy was managed and delivered on the island.

(Pictured above: PREPA Operating Account Balance With and Without Commonwealth Transfers)

The neglect of infrastructure maintenance during the economic decline had profound implications. The power grid, already outdated in many areas, became even more vulnerable to failures. This vulnerability was exposed dramatically with natural disasters like Hurricane Maria in 2017, where the lack of maintenance led to catastrophic system failures. The infrastructure wasn’t just old; it was also not built with modern standards for resilience against extreme weather events, which are becoming more common due to climate change.

Before the bankruptcy, there were attempts to address these issues through policy changes and investment in renewable energy. However, these efforts were often too little, too late, or mired in political and bureaucratic challenges. For instance, while there was a push towards solar power, particularly after the realization that decentralized, renewable energy could offer resilience against grid failures, the execution was slow due to financial constraints and regulatory hurdles.

The historical development of Puerto Rico’s energy infrastructure thus reflects a trajectory from optimism and expansion to one of struggle and decay. The initial reliance on hydroelectric power set a foundation for energy self-sufficiency, but the subsequent pivot to fossil fuels, without adequate planning for sustainability or the shocks of economic downturns, left PREPA and the island’s power system in a precarious state. The economic decline of the 2000s and the financial mismanagement that followed only deepened the crisis, leading to the current scenario where maintaining consistent power supply has become a significant challenge.

In essence, the historical context of Puerto Rico’s energy infrastructure is a narrative of ambition met with economic realities and natural limits. From the establishment of PREPA to leverage the island’s water resources, through the shift to fossil fuels to meet growing demand, to the financial collapse due to economic downturns, the story is one of adaptation, neglect, and the urgent need for systemic change to ensure a reliable and sustainable energy future for Puerto Rico.

Impact of Natural Disasters

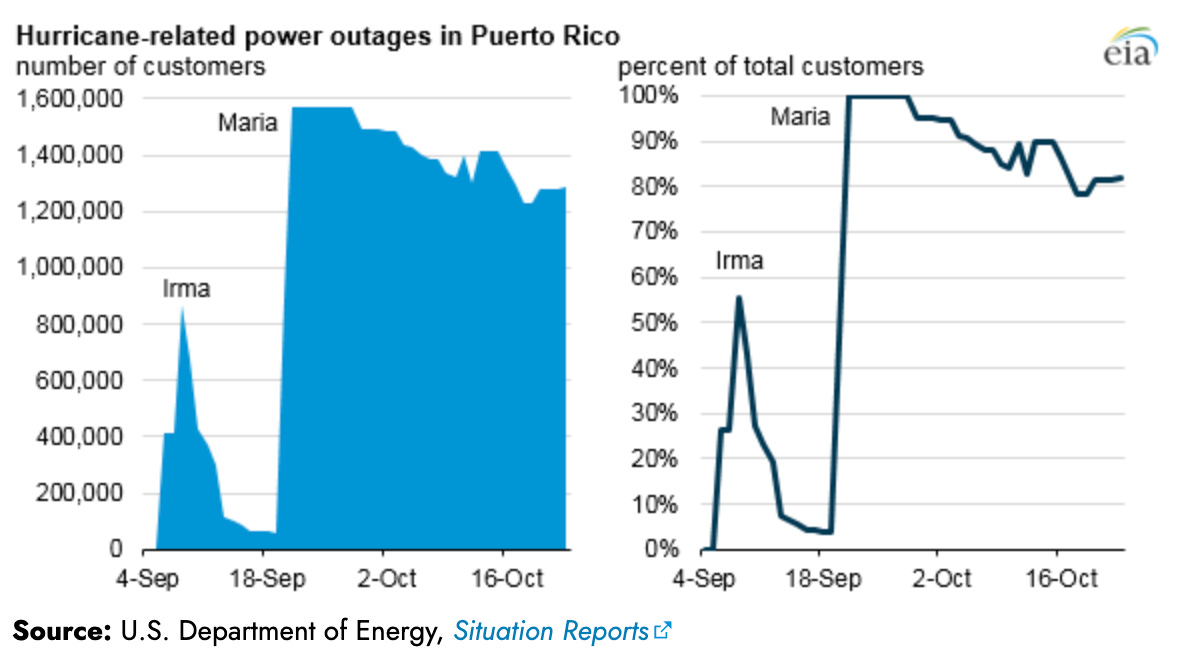

The impact of natural disasters on Puerto Rico’s electrical infrastructure has been profound, with Hurricanes Maria and Fiona serving as stark examples of how vulnerable and unprepared the system was. Hurricane Maria, a Category 4 storm, struck Puerto Rico in September 2017, bringing with it winds of up to 155 mph and causing what was described as the worst natural disaster to hit the island in modern history. The hurricane obliterated much of the existing power grid; over 80% of the transmission and distribution systems were damaged or destroyed, leading to the longest blackout in U.S. history at that time, with some areas waiting nearly a year for power restoration.

Maria’s impact was not just immediate but also illustrative of the long-term systemic issues within the energy sector. The storm knocked down power lines, damaged substations, and compromised power plants, some of which were already in a state of disrepair. The centralized nature of the grid meant that damage in one area could cascade across the entire island. The energy infrastructure was not only old and undermaintained but also lacked resilience features like underground cabling or distributed generation systems that could have mitigated the widespread power loss.

Hurricane Fiona, hitting Puerto Rico in September 2022, though less intense as a Category 1 storm, further highlighted the fragility of the recovery process post-Maria. Fiona brought heavy rains and flooding, causing another island-wide blackout, with over 1.5 million customers losing power. This event occurred just five years after Maria, and it showed that the infrastructure had not been sufficiently rebuilt or hardened against future storms. The electric grid, still in the process of being repaired from Maria, was once again thrown into chaos, demonstrating the lack of progress in making the system more resilient.

The long-term effects on infrastructure from these hurricanes have been extensive. Beyond the immediate physical damage, there was a significant human cost, with estimates of nearly 3,000 deaths attributed to Hurricane Maria largely due to the lack of power affecting healthcare, water purification, and basic living conditions. The infrastructure’s vulnerability to natural disasters also led to economic stagnation, as businesses could not operate, and tourism, a vital part of the economy, was severely impacted. The repeated failures of the electrical grid underscored the need for a fundamental rethinking of how energy is generated, distributed, and managed on the island.

Regarding rebuilding efforts after Maria, the influx of federal aid was substantial. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) had approved nearly $9.6 billion by 2020 for rebuilding the power grid, part of a larger pool of disaster relief funds. However, the utilization of these funds has been marred by various challenges.

The rebuilding of Puerto Rico’s electrical infrastructure post-Hurricane Maria was significantly delayed due to an array of bureaucratic and administrative challenges. One of the foremost hurdles was the sheer volume of red tape associated with project approval and execution. The process involved navigating through layers of bureaucratic requirements, which included detailed plans, environmental impact assessments, and compliance with federal regulations. This complexity often led to projects stalling at various stages of approval, causing frustration among local officials and residents eager for a swift recovery.

Disagreements over how to best allocate the billions in federal aid added another layer of delay. There was contention between different visions for Puerto Rico’s energy future: whether to rebuild the existing centralized grid or to invest in a more resilient, decentralized system with a greater emphasis on renewable energy. These disagreements not only slowed down decision-making but also led to debates about the prioritization of projects, with some arguing for immediate restoration over long-term resilience.

The controversies surrounding contracting practices in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria’s devastation on Puerto Rico’s electrical infrastructure were both numerous and deeply troubling, casting a long shadow over the recovery process. One of the most notorious examples was the contract awarded to Whitefish Energy Holdings, a small Montana company. With only two full-time employees when the hurricane struck, Whitefish was given a $300 million deal to repair and reconstruct large parts of the electrical grid. This decision was met with widespread criticism due to the company’s lack of experience in handling projects of this magnitude and because of its connections to political figures—specifically, to then-Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke, who hailed from Whitefish, Montana. The contract’s no-bid nature and the apparent bypassing of established procurement procedures fueled allegations of cronyism and corruption.

The public and political backlash was significant, leading to scrutiny from both local and federal levels. Congressional inquiries, audits by the Department of Homeland Security’s Inspector General, and reviews by Puerto Rican government officials ensued. The Whitefish contract was eventually canceled, but not before it had become a symbol of the broader issues with contracting practices during the emergency recovery phase. This incident was not an isolated case; other contracts were awarded with similar patterns of questionable oversight or due diligence, highlighting systemic problems in the emergency procurement process.

Another layer of controversy involved the apparent lack of competitive bidding for many reconstruction projects. The urgency following a disaster often leads to a relaxation of procurement rules, but in Puerto Rico, this resulted in contracts being awarded to firms with high costs or questionable capabilities. For example, PREPA (Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority) agreed to pay MasTec, a Florida-based construction firm, $400 per streetlight repair, a sum far exceeding local union estimates for the same work. Such pricing raised questions about whether the focus was on speed of recovery or on benefiting specific contractors.

(Pictured above: MasTec company released information on its efforts to Puerto Rico)

Moreover, there were stark allegations of funds being diverted from their intended use. Corruption was a significant concern, with stories emerging of kickbacks, fraudulent billing, and other malpractices. Investigations revealed instances where money meant for rebuilding was misappropriated, either through direct embezzlement or through less overt means like overcharging or unnecessary work. The lack of robust oversight allowed some to exploit the need for rapid recovery for personal or political gain, which not only delayed the actual reconstruction but also eroded public trust in the recovery process.

The mismanagement of funds was not just about corruption. It also involved poor project management where funds were spent inefficiently or on projects that did not contribute to long-term grid resilience. Projects were sometimes started without proper planning or were abandoned halfway, leaving infrastructure in a worse state than before. The inefficiencies were compounded by a lack of coordination between various agencies and contractors, leading to duplication of efforts or conflicting projects.

This environment of scandal and inefficiency led to a public outcry, with citizens and advocacy groups demanding more transparency and accountability. Local and national media coverage highlighted these issues, fueling protests and calls for reform. The controversies not only delayed the physical rebuilding but also the trust-building necessary for community recovery. The political fallout was significant, with officials losing credibility and some facing legal consequences, although enforcement of accountability was uneven due to the complexity of jurisdiction between local and federal authorities.

In response to the public and political pressure, there were attempts to reform the contracting process, including more stringent oversight mechanisms and efforts to involve local businesses more actively in the recovery to ensure funds directly benefited the local economy. However, these reforms came after much of the initial damage had been done, both to the infrastructure and to the public’s faith in the recovery process.

Ultimately, the controversies around contracting practices post-Maria in Puerto Rico illustrate a critical need for more transparent, competitive, and accountable procurement processes in disaster recovery scenarios. They underscore the delicate balance between the urgency of immediate action and the necessity for integrity in how public funds are managed and spent, especially in contexts where governance structures are already strained by the scale of the disaster.

The complexity of the federal grant process played a pivotal role in slowing down fund disbursement. The requirement for extensive documentation and compliance with environmental regulations meant that each project needed to pass through multiple checkpoints. This was meant to ensure that projects were both viable and environmentally sound, but in practice, it created bottlenecks. Coordination between local Puerto Rican agencies and various U.S. federal departments was often fraught with misunderstandings and miscommunications, further delaying the release of funds needed for reconstruction.

Oversight and accountability mechanisms were not sufficiently robust to prevent misuse of funds or to ensure that recovery efforts were on track. The lack of stringent monitoring allowed for some funds to be siphoned off or misused, either through direct corruption or through inefficiencies in project execution. This not only slowed down the physical rebuilding process but also undermined public trust in both the recovery efforts and in governance more broadly.

By the time Hurricane Fiona struck in 2022, much of the infrastructure improvements promised post-Maria were still pending or incomplete. The slow pace meant that the electrical grid remained vulnerable to another major storm. The incomplete projects included critical upgrades like the reinforcement of transmission lines, the modernization of power plants, and the installation of more resilient grid components that could withstand high winds and flooding. The delay in these projects left the island in a precarious position, essentially fighting the same battle against nature with an only partially repaired shield.

(Pictured above: An example of transmission line destruction post Fiona in Puerto Rico)

This situation highlighted a systemic issue in disaster recovery processes, where the urgency of immediate action is often at odds with the careful, sometimes slow, process of ensuring that funds are spent wisely and projects are sustainable. The aftermath of Maria and the unpreparedness for Fiona underscored the need for more agile, yet accountable, systems for managing disaster recovery funds, especially in regions like Puerto Rico, which are prone to such events due to climate change.

Ultimately, the challenges in rebuilding Puerto Rico’s electrical infrastructure post-Maria reveal a broader narrative about the difficulties of managing recovery in a colonial context, where local governance is constrained by federal oversight, and where the urgency of need clashes with the intricacies of administrative processes. These issues not only affected the timeline of recovery but also had deep implications for the economic and social recovery of the island, impacting everything from daily life to long-term development prospects.

Moreover, the execution of rebuilding projects was hindered by a lack of local capacity, both in terms of skilled labor and management. The island’s workforce did not have enough experienced engineers or technicians to handle the scale of reconstruction needed, leading to reliance on external contractors, some of whom were implicated in price gouging or delivering substandard work. This reliance also meant that local economic benefits from the recovery were not as significant as they could have been, further impacting the economy’s ability to recover.

Again, there was also a strategic debate about how to rebuild. Should the focus be on restoring the old centralized system, or should there be a shift towards decentralization with an emphasis on renewable energy like solar? This discussion was not just technical but also political, with differing visions for Puerto Rico’s energy future. The push towards renewables was seen as a way to achieve not just sustainability but also resilience, yet the transition was slow due to inertia in policy, existing investments in fossil fuel infrastructure, and the immediate need for power restoration.

The narrative of recovery post-Maria and Fiona also includes stories of community resilience and innovation, where local initiatives for solar power or microgrids emerged. These grassroots efforts provided some areas with quicker power restoration than the main grid could offer, highlighting a potential path forward but also revealing the need for more systemic support and integration of these solutions into broader energy policy.

In sum, the impact of Hurricanes Maria and Fiona on Puerto Rico’s electrical grid has been a lesson in the perils of neglecting infrastructure, the complexities of disaster recovery, and the urgent need for policy reforms to build a more resilient energy system. The journey from immediate disaster response through to long-term recovery underscores the challenges of governance, funding, and innovation in ensuring that Puerto Rico can keep the lights on in the face of both human-made vulnerabilities and natural disasters.

Recent Decision to Switch to Gas

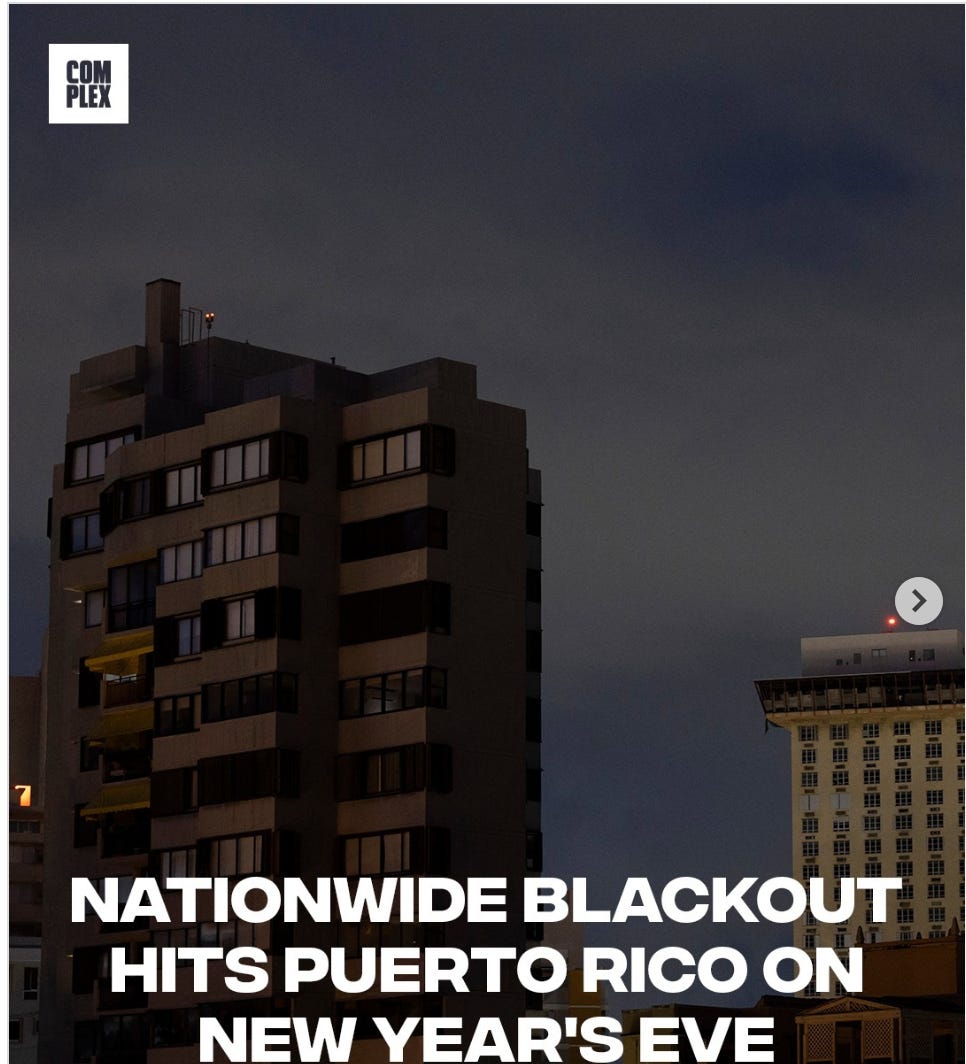

The recent decision announced yesterday (12/31/2024) by Puerto Rico to transition its energy production from a heavy reliance on petroleum to natural gas encapsulates both the island’s search for a more sustainable energy future and the practicalities of its current economic and environmental landscape. In the last several days leading up to January 1, 2025 (today), incoming Governor Jenniffer González of Puerto Rico has made significant statements regarding the transition to natural gas. On December 31, 2024, González publicly announced her administration’s intention to pivot towards natural gas as a means to stabilize the island’s fragile electrical grid. She stated that this move was crucial in addressing the ongoing energy crisis, emphasizing that natural gas could provide a more reliable energy source compared to the current reliance on solar and other renewable energies which, in her view, cannot deliver consistent 24/7 power. González suggested revising the island’s ambitious 100% renewable energy target by 2050, arguing that such a goal was not only unrealistic but also potentially damaging to economic activity.

(Pictured above: Incoming Governor Jenniffer González of Puerto Rico)

This stance by González was further elaborated during a press conference where she highlighted the need to balance environmental goals with practical energy needs. She noted that while the island would continue to support solar energy through net-metering to attract investment, the immediate focus would be on natural gas to reduce blackouts and stabilize electricity costs. This statement came in the context of a New Year’s Eve blackout that affected 1.3 million people, underscoring the urgency of her policy shift.

Governor González’s comments have been echoed, albeit indirectly, through various posts on social media, where it was noted that she believes the current clean energy targets are unrealistic. Her remarks indicate a policy direction that might involve altering the existing legal framework which mandates 100% renewable energy by 2050, suggesting a more pragmatic approach that incorporates natural gas as a significant component of the energy mix moving forward.

It is worth noting that these announcements come at a time when the outgoing Governor Pedro Pierluisi, just 10 days before leaving office on December 22, 2024, signed a contract for the construction and operation of a new natural gas power plant. This plant, expected to generate 478 megawatts using liquefied natural gas from 2028, is under the management of the consortium Energiza, which includes Tropigas, Cratos of Puerto Rico, and Mitsubishi. This decision by Pierluisi can be seen as laying some groundwork for González’s subsequent policy statements, signaling a continuity in policy direction towards natural gas.

(Pictured above: The newly authorized power plant in San Juan that will provide 478 megawatts of energy)

However, no further specifics from other Puerto Rican officials on this exact topic have been publicly documented or reported in the immediate days leading up to January 1, 2025. The statements by González and the actions by Pierluisi mark a clear shift or at least a significant adjustment in the energy policy narrative, focusing on natural gas to address immediate energy reliability issues while navigating the broader, long-term goals of energy transition and sustainability.

The motivation for this shift is multifaceted. Primarily, natural gas burns cleaner than oil and coal, producing less carbon dioxide and other pollutants, which aligns with global trends towards reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Additionally, natural gas has been seen as a cost-effective alternative to oil, especially given the volatile oil prices that have historically strained Puerto Rico’s energy budget. The lower cost per energy unit of natural gas, coupled with its abundance on the global market, presents an opportunity for more stable electricity pricing, which is crucial for an economy recovering from fiscal distress.

However, the transition to natural gas is not without its challenges. One of the foremost is the need for new infrastructure to transport and distribute natural gas across the island. This includes the construction of pipelines, storage facilities, and the conversion of existing power plants to run on gas. Given Puerto Rico’s geographical layout and its proneness to natural disasters, building such infrastructure is both costly and complex. There’s the issue of where to lay pipelines safely to avoid damage from hurricanes, earthquakes, or landslides, and ensuring that the infrastructure can withstand these conditions. Moreover, the conversion of power plants requires significant investment and time, both of which are in short supply on an island still reeling from economic constraints and the aftermath of natural disasters.

The environmental considerations of switching to natural gas are significant. While natural gas is cleaner than other fossil fuels in terms of emissions during combustion, it is not without environmental drawbacks. Methane, the primary component of natural gas, is a potent greenhouse gas if leaked during production, transport, or storage. Environmental impact assessments must account for potential methane leaks, which could negate some of the climate benefits of switching from oil. Public response has been mixed. Environmental groups argue that natural gas should not be seen as a long-term solution but rather as a bridge to fully renewable energy systems. Meanwhile, others see it as a pragmatic step towards reducing immediate pollution and improving air quality, particularly in areas near power plants.

Economically, the switch to natural gas offers potential benefits like lower operational costs for electricity generation, which could translate into reduced rates for consumers if managed correctly. However, these benefits are contingent upon the successful execution of infrastructure projects and stable gas prices, both of which are uncertain. The economic implications also include job creation during the construction phase, but there’s a risk that reliance on natural gas could delay the transition to renewable energy sources, potentially leading to stranded assets if global energy policies shift more aggressively towards sustainability.

The role of companies like New Fortress Energy in this transition is pivotal. New Fortress has been at the forefront of bringing natural gas to Puerto Rico, particularly through the development of LNG (Liquefied Natural Gas) import and regasification facilities. Their involvement has been controversial due to the speed at which they were able to bypass some regulatory processes, raising questions about transparency and environmental considerations. Critics argue that New Fortress’s aggressive expansion might lock Puerto Rico into a fossil fuel future longer than necessary, especially with their plans to convert key power stations like San Juan into gas-powered facilities. Supporters, however, highlight the speed and efficiency with which New Fortress has managed to bring energy solutions to the island, particularly post-disaster.

New Fortress’s projects have encountered legal and public scrutiny. For instance, their involvement in the conversion of the San Juan power plant faced challenges due to alleged misinformation to investors about the project’s progress and costs. This led to shareholder lawsuits, highlighting the complexities of private sector involvement in public infrastructure projects where profit motives might not align perfectly with public or environmental interests.

(Pictured above: a New Fortress Energy facility in Puerto Rico)

The transition also brings up discussions about energy sovereignty and security. By moving from oil to gas, Puerto Rico is still dependent on imported energy, which means any global supply disruption could impact local energy prices and availability. This dependency is particularly acute since Puerto Rico does not have its own natural gas reserves, making it reliant on foreign suppliers and vulnerable to international market dynamics.

The decision to switch to natural gas also intersects with broader energy policy debates in Puerto Rico, where there is a push for renewable energy integration. The tension lies in balancing immediate energy needs with long-term sustainability goals. Natural gas might serve as a necessary interim measure, providing baseline power while renewable technologies like solar and wind scale up and given that grid scale battery storage is not currently possible to combat the intermittent nature of renewable energies, but this requires a clear strategy to ensure that gas does not become a permanent fixture at the expense of green energy development.

Public perception and acceptance of this transition are crucial. There is a narrative of skepticism regarding the long-term benefits of natural gas, with many advocating for a direct leap to renewables. Community engagement, transparent environmental impact studies, and clear communication about the transition’s goals and outcomes are essential to maintain public trust and support for these policies.

In sum, Puerto Rico’s decision to transition from petroleum to natural gas is driven by the dual goals of economic viability and environmental improvement. While it offers immediate benefits in terms of cost and emissions compared to oil, the challenges are substantial, ranging from infrastructure development, environmental risks, to economic dependencies. The involvement of companies like New Fortress Energy brings both opportunities for rapid implementation and concerns about sustainability and governance. This transition moment is thus not just about changing fuel sources but about navigating a complex landscape of policy, economics, and environmental ethics in the pursuit of a more resilient and sustainable energy future for Puerto Rico.

The Jones Act Implications

The Jones Act, formally known as the Merchant Marine Act of 1920, is a piece of U.S. federal legislation that has significant implications for domestic maritime commerce, particularly affecting territories like Puerto Rico. At its core, the Jones Act mandates that all goods transported by water between U.S. ports must be carried on ships that are U.S.-built, U.S.-flagged, U.S.-owned, and crewed predominantly by U.S. citizens or permanent residents. This law was originally enacted to bolster the U.S. maritime industry after World War I, protect national security by ensuring a capable merchant marine, and support domestic shipbuilding and labor.

In relation to Puerto Rico’s energy supply, the Jones Act has a profound impact on the cost and efficiency of importing essential fuels like oil and natural gas. The requirement for using only American ships for domestic transport significantly increases shipping costs because U.S.-built ships are generally more expensive than their foreign counterparts due to higher labor and construction costs. This cost is then passed on through the supply chain, making energy in Puerto Rico more expensive. Additionally, the limited number of Jones Act-compliant vessels available for such transport means that there’s often less competition, which can lead to higher prices and less reliability in supply chains.

Specific examples highlight how these restrictions have adversely affected disaster recovery and routine maintenance of Puerto Rico’s energy infrastructure. After Hurricane Maria in 2017, the recovery process was significantly delayed due in part to the Jones Act. The immediate need for fuel to power generators and repair equipment was met with logistical bottlenecks because of the scarcity of compliant ships. For instance, ships carrying emergency supplies had to wait for available U.S.-flagged vessels, which delayed the delivery of diesel and other fuels critical for restoring power. Similar issues were observed post-Hurricane Fiona in 2022, where the Jones Act again contributed to delays in relief efforts, particularly for diesel imports needed for emergency operations.

The Jones Act’s impact on maintenance is equally concerning. The high cost of shipping within the U.S. due to the Act’s provisions discourages regular maintenance and upgrades of power infrastructure since the cost of bringing in repair materials or parts from the mainland is inflated. This has led to a cycle of neglect where infrastructure is only minimally maintained until a crisis forces action, further compounding the risk during natural disasters.

Regarding waivers and temporary relief, the U.S. government has occasionally granted Jones Act waivers during emergencies. These waivers allow foreign vessels to transport goods between U.S. ports, thereby speeding up disaster relief efforts. For example, after Hurricane Maria, President Trump approved a 10-day waiver, which was extended for another 10 days due to the severity of the situation. Similarly, following Hurricane Fiona, the Biden administration granted a targeted waiver for a BP tanker to deliver diesel to the island, recognizing the urgent need for fuel to operate emergency services and restore electricity. These waivers provide temporary relief, allowing for quicker importation of necessary supplies, but they are short-term solutions.

The effects of these waivers are generally positive in the immediate aftermath of disasters, facilitating faster recovery by circumventing the usual restrictions. However, they also highlight the inefficiencies of the Jones Act under normal circumstances. Critics argue that these waivers demonstrate how the law can be an impediment rather than an aid, especially in scenarios where time is of the essence. Each waiver, while helpful, also sparks debates about the broader implications of the Jones Act on Puerto Rico’s economy and energy security.

There is a significant call from various quarters, including Puerto Rican officials, economists, and policy analysts, for permanent changes or exceptions to the Jones Act specifically for Puerto Rico. They argue that the island’s unique geographical and economic situation merits special consideration. Advocates for reform point out that without the Jones Act, Puerto Rico could import energy resources more economically from closer international ports, reducing both costs and environmental impact from longer shipping routes to the mainland U.S.

The debate over the Jones Act also touches on national security and economic protectionism arguments. Proponents of the Act stress its role in maintaining a robust U.S. merchant marine for military purposes and supporting American jobs. However, in Puerto Rico’s context, this has often been seen as a case where the benefits to a small segment of the U.S. maritime industry come at a high cost to the island’s residents and economy.

In response to these criticisms, some political figures have proposed legislative changes to either exempt Puerto Rico from the Jones Act or to reform the Act to make it less restrictive for non-contiguous U.S. territories. Such proposals have met resistance from maritime unions and companies that benefit from the status quo, illustrating the political complexity of altering this century-old law.

In conclusion, the Jones Act’s implications for Puerto Rico’s energy supply are multifaceted, involving increased costs, supply inefficiencies, and delays in both disaster recovery and routine maintenance. While temporary waivers have provided some relief during acute crises, the broader consensus among many Puerto Rican stakeholders is that a more permanent solution is needed to address the underlying economic and logistical challenges posed by the Act. This situation underscores the tension between national policy objectives and the specific needs of territorial jurisdictions like Puerto Rico, where the balance between security, economic protection, and practical daily life remains a contentious issue.

Energy Policy in Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico’s energy policy is deeply intertwined with its status as a U.S. territory, which influences both its legislative capabilities and its economic framework for energy management. As a territory, Puerto Rico is subject to U.S. federal law, including policies and regulations from federal agencies like the Department of Energy. This status means that while Puerto Rico can establish its own energy legislation, it operates within the broader context of U.S. policy, sometimes limiting its ability to independently address its unique energy challenges. For instance, laws like the Jones Act directly affect energy costs and supply, while federal oversight can impact local energy initiatives and funding.

The legislative framework for energy in Puerto Rico has historically lacked incentives for significant infrastructure investment, largely due to the island’s economic struggles. The territory has been facing economic downturns, with high debt levels, unemployment, and a shrinking population, which have all contributed to a lack of capital for maintaining or upgrading the energy grid. The Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority (PREPA), responsible for electricity generation, transmission, and distribution, has been particularly affected by these economic woes, leading to deferred maintenance and an aging, vulnerable electrical infrastructure.

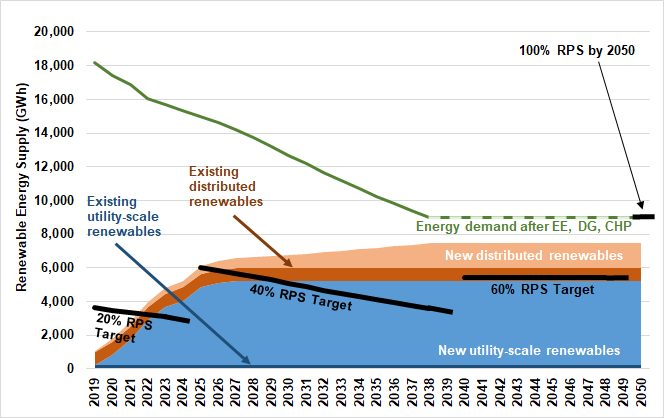

One of the most significant pieces of energy legislation in recent years is the Puerto Rico Energy Public Policy Act (Act 17) of 2019. This act represents a pivotal change in the island’s approach to energy, aiming to modernize and transform its energy sector. Act 17 set ambitious targets, including obtaining 40% of electricity from renewable resources by 2025, increasing to 60% by 2040, and achieving 100% renewable energy by 2050. Additionally, it mandates the phase-out of coal-fired power plants by 2028, reflecting a strong commitment to reducing carbon emissions and moving towards sustainability. The act also includes provisions for improving energy efficiency, with goals for a 30% improvement by 2040.

In terms of renewable energy integration, the push in Puerto Rico has been marked by both progress and significant challenges. Solar energy has been a focal point, with numerous solar installations, particularly after Hurricane Maria highlighted the resilience of decentralized solar systems. The government has tried to incentivize solar through net metering policies, but the adoption rate, while growing, faces barriers. These include the high initial cost of solar installations, especially for those in lower-income brackets, bureaucratic hurdles in connecting to the grid, and the intermittent nature of solar power which requires robust storage solutions or backup systems. Despite these challenges, solar has made inroads, with community solar projects and private initiatives gaining ground, though not at the pace needed to meet the ambitious targets set by Act 17.

The privatization of Puerto Rico’s energy sector marked a significant policy shift aimed at addressing the longstanding inefficiencies and financial burdens of the Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority (PREPA). In June 2021, the management of electricity transmission and distribution was transferred from PREPA to LUMA Energy, a joint venture between Houston’s Quanta Services Inc. and ATCO Group from Canada. This move was part of a broader strategy to inject expertise, technology, and capital into an energy system that had been plagued by chronic blackouts, high costs, and an infrastructure in dire need of overhaul. The idea was to leverage private sector capabilities to achieve what the public sector had struggled with for decades, including improving service reliability and introducing modern management practices.

The decision to privatize was also influenced by PREPA’s bankruptcy in 2017, which underscored the need for a new approach to manage its $9 billion debt and to fund necessary upgrades. LUMA Energy was given a 15-year contract, with expectations that it would not only maintain but also modernize the grid, aiming to reduce power outages and enhance the integration of renewable energy sources. However, from the outset, the transition was fraught with controversy. Critics pointed to the lack of transparency in the contract negotiations, the high costs associated with LUMA’s operations, and the perceived lack of immediate improvement in service quality.

By 2023, this privatization strategy extended to the generation side of the energy sector with Genera PR, a subsidiary of New Fortress Energy, taking over the operations, maintenance, and eventual decommissioning of PREPA’s power generation units under a 10-year contract. This move was intended to complement LUMA’s efforts by focusing on the generation infrastructure, which was equally antiquated and inefficient. The hope was that Genera PR would bring about better management of power plants, optimize fuel usage, and possibly pave the way for more renewable energy projects.

However, these privatization efforts have elicited mixed reactions among Puerto Ricans. On one hand, there was an expectation that private companies with global experience would bring much-needed investment and innovation to the energy sector. On the other hand, there has been significant public and political backlash. Many residents and local officials have criticized the continued power outages, arguing that the situation has not improved substantially post-privatization. The privatization has been seen by some as a continuation of colonial economic policies where external companies profit while local conditions remain static or worsen.

The public discourse has highlighted several issues. Firstly, there is concern over the cost of electricity. Despite the promise of efficiency, rates have not decreased, and in some cases, they have increased, placing a further burden on residents amidst economic recovery efforts. Secondly, there are worries about job security and the future of PREPA workers, with fears of job losses or the need to reapply for positions under new management, potentially under less favorable conditions. This has led to strikes and protests by unions like the Union of Electrical and Irrigation Industry Workers (UTIER).

Moreover, there is an ongoing debate about accountability and performance. LUMA Energy and Genera PR have faced criticism for their response to natural disasters and the general maintenance of the grid. While they’ve pointed to inherited problems and the need for extensive repairs, the public’s patience has been tested by recurring blackouts, especially during critical times like hurricane seasons or heatwaves.

Politically, the privatization has become a contentious topic, with candidates and political groups using it as a campaign issue, promising to review or even cancel these contracts if elected. There is a call for more stringent oversight by the Puerto Rico Energy Bureau (PREB) to ensure that these private entities are indeed working towards the public interest, focusing on reliability, cost-effectiveness, and the transition to renewable energy as outlined in policy acts like Act 17.

The narrative around privatization in Puerto Rico is thus one of potential versus reality. While the influx of private capital and expertise promised modernization and efficiency, the actual outcomes have been less than transformative for many, leading to a critical examination of whether privatization is the right path forward for the island’s energy needs. This situation underscores the complexities of managing energy policy in a territory where economic, environmental, and social factors intersect in unique ways, demanding a nuanced approach that balances local needs with global economic dynamics.

Public and political reactions to privatization have been complex. There have been criticisms regarding the performance of LUMA Energy, particularly around the continued frequency of blackouts and perceived high operational costs. Many residents and local politicians have voiced concerns over rate increases and whether privatization truly benefits the public or primarily the private companies. There is also been contention over how privatization affects local jobs, with fears of layoffs and the outsourcing of skilled labor. Public protests and legal challenges have arisen, with some arguing that privatization has not visibly improved service reliability as hoped.

The transition to private management has also brought scrutiny to the contracts and their terms. The initial contract with LUMA was criticized for its lack of transparency and for potentially favoring the company with terms that might not prioritize local interests. The oversight of these private entities by the Puerto Rico Energy Bureau (PREB), meant to regulate and ensure compliance with public policy, has been under the microscope, with questions about its independence and effectiveness in representing public interests against corporate ones.

Despite the push for renewable energy, the reliability issues persist, partly because the infrastructure’s fundamental problems were not solely due to PREPA’s management but also due to long-standing underinvestment and natural disaster impacts. The privatization efforts are thus seen by some as a necessary but not sufficient step towards solving the energy crisis. There is a call for more systemic changes, including decentralizing the grid with microgrids, enhancing local renewable energy production, and rethinking how energy policy can truly serve the island’s unique socio-economic landscape.

(Pictured above: A denuded turbine at the Punta Lima wind farm. Photo: Erika P. Rodriguez)

The overall energy policy landscape in Puerto Rico is thus one of transition, ambition, and significant challenges. There is no unified vision. The legislative framework through Act 17 sets a progressive vision, yet the reality of implementing these policies is complicated or made truly impossible by economic constraints, federal oversight, and the need for substantial investment in infrastructure. Privatization has been a controversial strategy, viewed by some as a potential solution and by others as a shift that might not fully address the root issues. So far, its results have been disappointing. Moving forward, the success of Puerto Rico’s energy policy will depend on balancing these elements, ensuring that reforms lead to a resilient, sustainable, and equitable energy system for all its residents.

(Pictured above: The Act 19 ambitious plan for energy)

Structural and Operational Challenges

The structural and operational challenges facing Puerto Rico’s energy sector are deeply rooted in the design, management, and technological aspects of its electrical grid. One of the primary issues is the grid’s design, which has been predominantly centralized. In a centralized system, power generation occurs at large power plants, and electricity is then transmitted over long distances to consumers through a network of high-voltage transmission lines. This setup contrasts with a decentralized system where power generation happens closer to or at the point of consumption, often through smaller, distributed sources like solar panels or wind turbines. But making a fully decentralized energy grid presents large issues related to intermittency as grid sized battery storage does not exist. Puerto Rico’s centralized grid, with its reliance on a few large power plants and extensive transmission lines, makes it particularly vulnerable to weather events. When a storm hits, it can damage critical points of this centralized structure, leading to widespread outages as seen with Hurricanes Maria and Fiona.

(Pictured above: Broken solar panels in Humacao.Photo: Erika P. Rodriguez)

The vulnerability is exacerbated by the geographical layout of Puerto Rico, with its mountainous terrain and coastal exposure, making the maintenance of overhead lines challenging. When these lines are downed or damaged, restoring power can take an inordinate amount of time due to the need to repair or rebuild significant portions of the grid. The centralized design also means that if one major power plant goes offline, it can affect the entire grid’s stability, unlike in decentralized systems where local generation can continue to supply power independently.

(Pictured above: Transmission lines cut through mountainous terrain.Photo: Erika P. Rodriguez)

Maintenance and management issues further compound the challenges. PREPA, which managed the grid for decades, has a legacy of mismanagement and inadequate maintenance. Over time, there were allegations of corruption, with funds that should have been allocated for upkeep being misused or mismanaged. This resulted in an infrastructure that was not only aging but also neglected. The financial distress of PREPA, culminating in its 2017 bankruptcy, meant that there was little capital available for necessary upgrades or even routine maintenance. The transition to new operators like LUMA Energy for transmission and distribution, and Genera PR for generation, was intended to address these issues but has introduced its own set of challenges during the transition phase.

The transition itself has been criticized for its execution. The new operators have inherited a system in disrepair, and while they bring in new management practices and potentially more funds, the immediate impacts on service reliability have not been as positive as hoped. There has been public discontent over the perceived slow pace of improvement, continued high costs, and the persistence of power outages. Moreover, the change from public to private management has raised concerns about accountability, with questions about whether these private entities are more focused on profit than on service improvement.

Technological limitations are another significant barrier. Much of Puerto Rico’s grid relies on technology that is decades old, not designed to handle modern energy demands or the integration of renewable energy sources efficiently. The lack of investment in modern grid solutions like smart grid technologies, which can automatically reroute power or manage demand more effectively, has left the system lagging. Smart meters, for instance, are not universally implemented, limiting the ability to manage energy distribution in real-time or to educate consumers on usage for better energy conservation.

The integration of renewable energy, particularly solar, into such an outdated system poses additional challenges. Solar energy, while abundant in Puerto Rico, requires grid infrastructure that can handle variability and reverse power flows when generation exceeds local consumption. Without the appropriate technology, like advanced inverters or substantial battery storage, the grid can become unstable, leading to issues like voltage fluctuations or the need for curtailment of solar power during peak generation times.

Human resource aspects also play a critical role. The energy sector in Puerto Rico has faced a shortage of skilled workers, particularly in engineering, maintenance, and technical roles. This is partly due to the brain drain the island has experienced, where skilled individuals seek opportunities elsewhere. The transition to new operators brought some hope for job creation or skill development, but the pace has been slow, and there is resistance from unions over job security and conditions under private management. Training and retaining a workforce capable of managing a modern, resilient energy system is a continuous challenge.

The lack of investment in human capital also means that there is a gap in expertise for dealing with the unique aspects of Puerto Rico’s energy needs, from managing a grid under constant threat from natural disasters to integrating local renewable resources effectively. This is not just about having enough workers but ensuring they are trained in the latest technologies and practices that could mitigate some of the grid’s vulnerabilities.

In essence, the structural and operational challenges of Puerto Rico’s energy sector are multifaceted, involving not only the physical design of the grid but also the historical context of its management, the technological state of its infrastructure, and the human resources available to maintain and innovate. These challenges necessitate a holistic approach to reform, one that considers both the immediate need for reliable energy and the long-term vision for a sustainable, resilient energy system. Only by addressing these issues comprehensively can Puerto Rico hope to transition from a scenario of chronic blackouts to one where energy is dependable, cost-effective, and environmentally friendly.

(Pictured above: Obed Santos, manager of the AES Illumina solar farm in Guayama.Photo: Erika P. Rodriguez)

Social and Economic Impact

The social and economic impacts of the persistent power outages in Puerto Rico are profound, affecting every aspect of daily life, health services, and the broader economic landscape of the island. In terms of daily life, blackouts disrupt basic routines, from cooking and preserving food to maintaining hygiene, particularly in the hot and humid climate of Puerto Rico where air conditioning is often a necessity. People are forced to adapt, using candles or gas stoves, which not only inconvenience but also increase the risk of fires and carbon monoxide poisoning from using indoor generators or grills.

The health sector is particularly vulnerable to these disruptions. Hospitals and clinics rely heavily on a constant power supply for critical equipment like ventilators, dialysis machines, and refrigeration for medicines. During blackouts, even facilities with backup generators can face challenges due to fuel shortages or mechanical failures, leading to compromised care or even the suspension of surgeries and treatments. For individuals dependent on home medical equipment, such as oxygen concentrators or insulin refrigeration, power outages can be life-threatening. Moreover, the lack of electricity impacts water treatment and distribution, raising public health risks from contaminated water supplies.

Emergency responses are significantly hampered by unreliable power. Communication systems often fail, making it difficult to coordinate rescues, medical evacuations, or disaster response efforts. The absence of street lighting and traffic signals leads to increased traffic accidents and can delay emergency services from reaching those in need. The psychological toll on the population is also considerable, with increased stress and anxiety from living in a state of perpetual uncertainty about when the next blackout will occur or how long it will last.

On the economic front, the impact on businesses is devastating. Small businesses, which form the backbone of Puerto Rico’s economy, suffer from lost productivity each time there’s an outage. Perishable goods spoil, electronic equipment can be damaged by surges, and without electricity, many businesses simply cannot operate, leading to lost income and potential closure. Larger companies might have backup systems, but these are costly, adding to operational expenses and reducing competitiveness.

Tourism, a vital sector for Puerto Rico’s economy, is adversely affected by these conditions. Tourists expect a certain level of comfort and reliability, including consistent electricity for hotels, restaurants, and attractions. Frequent blackouts can deter tourists, leading to cancellations, reduced bookings, and a tarnished reputation for the island as a travel destination. This not only affects immediate revenue but also long-term tourism development and investment.

The overall economic stability of Puerto Rico is undermined by these energy issues. Investors are hesitant to commit when the reliability of the power supply is in question, which slows down economic recovery and growth. The unpredictability of the energy situation leads to higher operational costs for all sectors, as businesses must invest in alternative energy solutions or bear the cost of downtime. This environment fosters economic stagnation, where potential growth is curtailed by the need to address immediate survival rather than expansion or innovation.

Future Outlook

From a pessimistic perspective, the short-term outlook for significant improvement in Puerto Rico’s energy reliability does not seem promising. The transition to new private management has not yet yielded the expected improvements in grid stability, and the frequency of blackouts continues to challenge daily life and economic operations. The political and administrative will to enact rapid, effective changes is often bogged down by bureaucratic delays, corruption scandals, or disputes over privatization policies.

In the long term, the lack of a unified vision for Puerto Rico’s energy future exacerbates the problem. Without a clear, agreed-upon strategy that integrates base load energy, modernizes the grid, and ensures resilience against natural disasters, the cycle of neglect and emergency response is likely to continue. The island’s challenge is not just in repairing or upgrading infrastructure but in doing so with the appropriate skilled workforce. There is a shortage of engineers, technicians, and project managers who can drive such a transformation, and the exodus of skilled labor from Puerto Rico only deepens this crisis.

Furthermore, large investments in infrastructure are necessary, but these are hindered by the island’s economic situation and external factors like the Jones Act. This act increases the cost of materials for repair and maintenance, making any major overhaul more expensive and time-consuming. Without significant federal aid, relaxed regulations, or a repeal of such laws, the financial burden of making the grid resilient and modern will remain daunting.

Thus, without a cohesive approach that includes substantial investment, policy reform, and development of local expertise, the future for Puerto Rico’s energy sector looks bleak. The combination of these factors not only discourages both local and international investment but also perpetuates a scenario where economic recovery remains elusive, and the social fabric continues to fray under the strain of unreliable energy. This situation underscores the need for not just immediate action but a comprehensive, long-term strategy that acknowledges the island’s unique challenges and leverages its potential for sustainable development.

Conclusion

Puerto Rico’s persistent struggle to maintain a reliable power supply is a multifaceted crisis shaped by historical neglect, financial mismanagement, political inefficiencies, and the island’s vulnerability to natural disasters. The shift to privatized management and the recent decision to embrace natural gas represent attempts to address immediate concerns, but these solutions are fraught with challenges. From systemic corruption and bureaucratic delays to the high costs imposed by the Jones Act and the technical limitations of aging infrastructure, the road to energy stability remains daunting.

Looking forward, Puerto Rico’s energy future demands a comprehensive and coordinated approach. This includes investing in modern grid technology, fostering base load energy solutions, and addressing structural inefficiencies in governance and policy. Equally crucial is the need for resilience—adapting infrastructure to withstand increasingly frequent and severe natural disasters. Achieving energy independence and reliability will also require local workforce development, community engagement, and a re-evaluation of federal policies that disproportionately burden the island.

Puerto Rico stands at a critical juncture. While its energy challenges are daunting, they also present an opportunity for transformation. By leveraging its abundant solar resources, fostering innovation, and ensuring transparent, equitable reforms, Puerto Rico can emerge as a model for sustainable and resilient energy systems in the face of adversity. Only with bold vision, determined leadership, and collaboration at all levels can the island finally keep the lights on for its people, ensuring a brighter and more stable future.

Sources:

-

Why it’s so hard to turn the lights back on in Puerto Rico. (2017, October 20). NPR. https://www.npr.org/2017/10/20/558743790/why-its-so-hard-to-turn-the-lights-back-on-in-puerto

-

Why it’s so hard to keep the lights on in Puerto Rico. (n.d.). Americas Quarterly. https://www.americasquarterly.org/article/why-its-so-hard-to-keep-the-lights-on-in-puerto-rico/

-

Will city ordinance mean lights out for Puerto Rico’s hottest nightspots? (n.d.). Global Press Journal. https://globalpressjournal.com/americas/puerto-rico/will-city-ordinance-mean-lights-puerto-ricos-hottest-nightspots/

-

Declet-Barreto, J. (n.d.). Seven years after Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico, you can’t even count on keeping the lights on. Union of Concerned Scientists. https://blog.ucsusa.org/juan-declet-barreto/seven-years-after-hurricane-maria-in-puerto-rico-you-cant-even-count-on-keeping-the-lights-on/

-

Puerto Rico: How a New Year’s Eve blackout plunged the island into darkness. (n.d.). BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c8782rvv5xxo

-

Do whatever it takes to turn the lights back on in Puerto Rico. (2017, September 21). New York Post. https://nypost.com/2017/09/21/do-whatever-it-takes-to-turn-the-lights-back-on-in-puerto-rico/

-

Puerto Rico’s electricity: Video shows lights turn on for first time in weeks. (2018, January 19). The Independent. https://www.the-independent.com/news/world/americas/puerto-rico-electricty-video-lights-turn-on-power-outages-grid-storm-island-us-a8165996.html

-

Puerto Rico power outage leaves nearly 1 million without electricity. (n.d.). NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/puerto-rico-power-outage-rcna185849

-

Puerto Rico suffers massive power outage on New Year’s Eve. (n.d.). CBS News. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/puerto-rico-power-outage-blackout-new-years-eve-power-grid-electricity/

-

Puerto Rico blackout: Nearly 1.3 million without power at New Year. (2024, December 31). The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2024/dec/31/puerto-rico-blackout-power-grid

-

Why the lights went out in Puerto Rico. (n.d.). Public Books. https://www.publicbooks.org/why-the-lights-went-out-in-puerto-rico/

-

Puerto Rico without power as New Year’s Eve blackout hits island. (2024, December 31). CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2024/12/31/us/puerto-rico-power-outage/index.html

-

Puerto Rico’s long struggle to keep the lights on. (n.d.). The Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/podcasts/the-journal/puerto-rico-long-struggle-to-keep-the-lights-on/38c20829-0baa-47ed-9c8c-0c7f315eb9ec

-

Puerto Rico enters New Year with near-total blackout. (2024, December 31). POLITICO. https://www.politico.com/news/2024/12/31/puerto-rico-near-total-blackout-00196163

-

Puerto Rican blackouts raise concerns ahead of hurricane season. (2023, March 28). POLITICO. https://www.politico.com/news/2023/03/28/puerto-rican-blackouts-hurricane-season-00089007

-

Puerto Rico’s power grid still struggling 7 years after Hurricane Maria. (n.d.). ABC News. https://abcnews.go.com/Technology/puerto-ricos-power-grid-struggling-years-hurricane-maria/story?id=90151141

-

Puerto Rico marks Hurricane Maria anniversary with ongoing power grid issues. (n.d.). NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/latino/puerto-rico-hurricane-maria-anniversary-power-grid-rcna47729

-

Puerto Rico’s infrastructure is still recovering from Hurricane Maria 7 years later. (n.d.). ABC News. https://abcnews.go.com/US/puerto-ricos-infrastructure-recovering-hurricane-maria-7-years/story?id=113672746

-

Puerto Rico Grid Recovery and Modernization. (n.d.). U.S. Department of Energy. https://www.energy.gov/gdo/puerto-rico-grid-recovery-and-modernization

-

The impact of Hurricane Fiona on Puerto Rico. (2022, September 23). NPR. https://www.npr.org/2022/09/23/1124345084/impact-hurricane-fiona-puerto-rico

-

How to protect Puerto Rico’s power grid from hurricanes. (n.d.). Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/how-to-protect-puerto-ricos-power-grid-from-hurricanes/

-

Puerto Rico Recovery Overview 2024. (n.d.). FEMA. https://www.fema.gov/case-study/puerto-rico-recovery-overview-2024

-

Puerto Rico’s vulnerability to hurricanes magnified by weak government and bureaucratic roadblocks. (n.d.). PreventionWeb. https://www.preventionweb.net/news/puerto-ricos-vulnerability-hurricanes-magnified-weak-government-and-bureaucratic-roadblocks

-

Hurricane Fiona: Puerto Ricans frustrated with electric grid infrastructure. (n.d.). ABC News. https://abcnews.go.com/US/hurricane-fiona-puerto-ricans-frustrated-electric-grid-infrastructure/story?id=90262537

-

Hurricane Fiona leaves Puerto Rico’s electrical grid in shambles. (2022, October 1). CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2022/10/01/us/hurricane-fiona-puerto-rico-electrical-grid/index.html

-

Puerto Rico’s electricity problems go beyond Maria and Fiona. (2022, September 28). The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2022/09/28/puerto-ricos-electricity-problems-go-beyond-mara-fiona/

-

What has happened to Puerto Rico’s power grid since Hurricane Maria? (2022, September 19). Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/americas/what-has-happened-puerto-ricos-power-grid-since-hurricane-maria-2022-09-19/

-

Puerto Rico’s Energy Bridge: Natural Gas. (n.d.). The National Interest. https://nationalinterest.org/blog/techland/puerto-rico%E2%80%99s-energy-bridge-natural-gas-214204

-

Puerto Rico hands control of its power plants to a natural gas company. (2023, January 26). Inside Climate News. https://insideclimatenews.org/news/26012023/puerto-rico-hands-control-of-its-power-plants-to-a-natural-gas-company/

-

Let’s Get Going: Next Steps in Puerto Rico’s Energy Transformation. (2024, May 21). Grupo CNE. https://grupocne.org/2024/05/21/lets-get-going-next-steps-in-puerto-ricos-energy-transformation/

-

Puerto Rico – Oil & Gas Laws and Regulations. (n.d.). ICLG. https://iclg.com/practice-areas/oil-and-gas-laws-and-regulations/puerto-rico

-

Puerto Rico’s Energy Future: Solar or Natural Gas? (2020, February 9). The Intercept. https://theintercept.com/2020/02/09/puerto-rico-energy-electricity-solar-natural-gas/

-

Puerto Rico is pushing LNG when it’s supposed to be shifting to renewables. (n.d.). Canary Media. https://www.canarymedia.com/articles/fossil-fuels/puerto-rico-is-pushing-lng-when-its-supposed-to-be-shifting-to-renewables

-

Biden administration supports Puerto Rico’s renewable energy ambitions. (2021, October 25). Inside Climate News. https://insideclimatenews.org/news/25102021/puerto-rico-renewable-energy-biden-administration/

-

Here’s How to Lift Puerto Rico with Natural Gas. (n.d.). Natural Gas Now. https://naturalgasnow.org/heres-lift-puerto-rico-natural-gas/

-

Lawsuit challenges project expanding liquefied natural gas shipping to Puerto Rico. (2022, August 16). Center for Biological Diversity. https://biologicaldiversity.org/w/news/press-releases/lawsuit-challenges-project-expanding-liquified-natural-gas-shipping-to-puerto-rico-2022-08-16/

-

Puerto Rico LNG Facility. (n.d.). New Fortress Energy. https://www.newfortressenergy.com/operations/PuertoRico-LNG-facility

-

The Jones Act: A red herring in the debate on Puerto Rico’s energy situation. (n.d.). American Maritime Partnership. https://www.americanmaritimepartnership.com/press-releases/the-jones-act-a-red-herring-in-the-debate-on-puerto-ricos-energy-situation/

-

Puerto Rico: The Jones Act—The Urgency of Modernizing Energy Policy. (2022, September 28). America First Policy Institute. https://americafirstpolicy.com/issues/20220928-puerto-rico-the-jones-actthe-urgency-of-modernizing-energy-policy

-

The Jones Act is forcing Puerto Rico to overpay for energy. (n.d.). Instituto de Libertad Económica. https://institutodelibertadeconomica.org/en/publications/the-jones-act-is-forcing-puerto-rico-to-overpay-for-energy/

-

Push to reverse obscure shipping law could flood Puerto Rico with fracked gas. (2019, April 1). Nation of Change. https://www.nationofchange.org/2019/04/01/push-to-reverse-obscure-shipping-law-could-flood-puerto-rico-with-fracked-gas/

-

A private company provokes an energy crisis in Puerto Rico. (n.d.). New Lines Magazine. https://newlinesmag.com/reportage/a-private-company-provokes-an-energy-crisis-in-puerto-rico/

-

Fuera Luma: Puerto Rico Confronts Neoliberal Electricity System Takeover Amid Ongoing Struggles for Self-Determination. (2021, June 21). Georgetown Journal of International Affairs. https://gjia.georgetown.edu/2021/06/21/fuera-luma-puerto-rico-confronts-neoliberal-electricity-system-takeover-amid-ongoing-struggles-for-self-determination/

-

Out Luma: Puerto Ricans Demand an End to the Privatization of Energy. (2024, July 5). People’s Dispatch. https://peoplesdispatch.org/2024/07/05/out-luma-puerto-ricans-demand-an-end-to-the-privatization-of-energy/

-

Puerto Rico officially privatizes power generation with Genera PR. (n.d.). NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/latino/puerto-rico-officially-privatizes-power-generation-genera-pr-rcna67284

-

The Fate of Puerto Rico’s Electrical Grid Lies in a Public-Private Partnership. (2023, March 23). GPP Review. https://gppreview.com/2023/03/23/the-fate-of-puerto-ricos-electrical-grid-lies-in-a-public-private-partnership/

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post