Recycling asphalt pavement can help the environment − now scientists are putting the safet

May 8, 2025

More than 90% of paved roads in the U.S. are made of asphalt, which is constructed with nonrenewable materials such as petroleum. One way to make paving more sustainable is to recycle old pavement. When roads break down and need repaving, transportation agencies can recycle their old pavement into a reusable material called reclaimed asphalt pavement, or RAP. This method reduces carbon emissions and conserves natural resources.

Nearly 95% of new asphalt pavement projects in the U.S. incorporate RAP.

However, researchers don’t know as much about the long-term safety and durability of RAP as they do about new pavement.

So, can engineers make roads more sustainable without compromising safety? As civil engineering researchers at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, we’re working with our state’s transportation department to help answer this question.

RAP and friction

Asphalt pavement is composed of asphalt binder and aggregates. Asphalt binder is typically sticky and black petroleum-based material that acts as glue, holding the pavement together.

Aggregates are solid materials, such as crushed stone, gravel or sand. The pavement manufacturers coat these aggregates with asphalt to bind them together and create a durable road surface. But both of these materials are nonrenewable.

One way to reduce the demand for new aggregates is by recycling old pavement. Contractors use a milling machine to grind up the existing pavement surface. The milled material is then reused: The old aggregates and asphalt binder from the road become part of the new mixture. These old materials are often blended with new binder and additional aggregates to make sure they can perform well.

Why study RAP’s properties?

One challenge with using RAP is that its properties vary significantly. RAP typically look black, since they are fully coated in asphalt. Researchers have a hard time visually inspecting them to identify the aggregate types, shapes or textures. But we developed testing procedures to measure these properties.

The road’s ability to grip the tires, known as skid resistance, keeps vehicles from skidding or hydroplaning during wet conditions. Skid resistance is typically quantified by measuring a coefficient of friction between the tire and the pavement surface.

Pavement friction is the force that resists the motion between a vehicle’s tire and the pavement’s surface. More friction means a vehicle is less likely to skid.

Understanding RAP’s skid resistance-related properties is important because these attributes affect how safe the pavement is, especially when it’s wet.

Nearly 75% of weather-related accidents occur on wet pavement. At low speeds, most of the skid resistance between a tire and the pavement comes from the texture of the aggregates.

Most friction research has tested new aggregates. RAP needs to maintain good frictional properties to be as safe as the original, but until now, researchers haven’t fully investigated whether it does.

How we study RAP’s properties

Our research team developed a two-step process to better understand RAP’s safety performance. First, we extract the aggregates from the RAP. Then, we measure the frictional properties of those aggregates, since they play a key role in pavement skid resistance.

The University of Tennessee research team

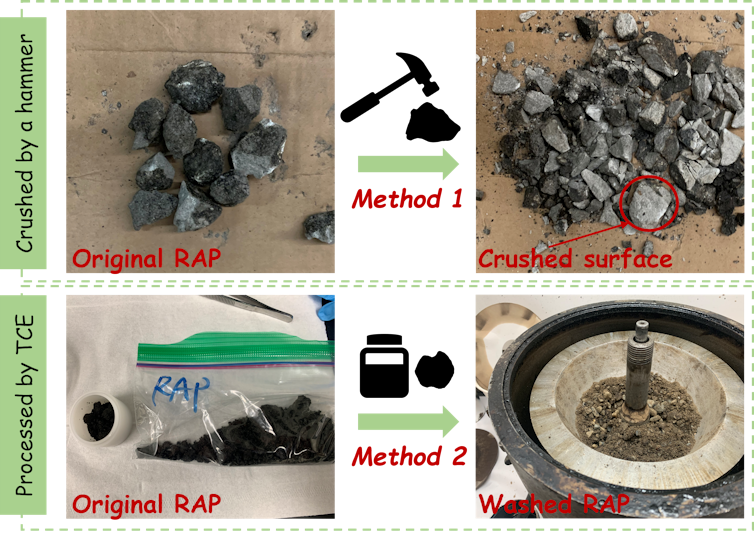

To remove the black asphalt coating and expose the actual surface of the aggregates, we use two simple methods. The first is a mechanical method, where we crush the RAP using a hammer to expose the surface inside. The second is a chemical procedure, where we use a solvent to dissolve asphalt and leave the aggregates for further testing.

Once we’ve cleaned the aggregates, we analyze their chemical composition and see how it relates to friction. One factor we look for is the hardness of the minerals in the aggregate. Harder minerals, such as silica, provide better friction as they keep their texture better over time instead of wearing down under traffic.

The University of Tennessee research team

We also use an aggregate image measurement system, which takes high-resolution images and analyzes the shape, angularity − the sharpness of the aggregate particles − and surface texture of the aggregates. These properties relate directly to skid resistance.

Understanding the frictional properties of RAP − and, specifically, how silica content affects skid resistance − helps engineers determine whether an RAP mixture is safe for a road’s curves or intersections. These insights can guide how much RAP transportation departments can use, and where, without compromising safety. We hope our research will lead to solutions that reduce carbon emissions, conserve natural resources and keep roads safe over time.

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post