Social rank and social environment combinedly affect REM sleep in mice

January 19, 2026

Abstract

The interplay of sleep quality, social hierarchy, and social isolation remains elusive. We evaluated such interplay using two mouse lines: C57BL/6J (B6) mice with relatively weak social hierarchy, and ICR×B6 F1 hybrid mice with relatively robust social hierarchy. Considering the potential effects of group housing on sleep – both through direct physical contact and other social interactions, which complicates interpretation—we designed a neighbor-housing condition that eliminates effects of direct physical contact while preserving social context. Under this condition, sleep architecture did not differ significantly between dominant and subordinate mice of either line. Under the single-housing condition, sleep differences emerged, some of which depended on both social rank and mouse line. In both mouse lines, single housing had opposite effects on oscillatory activities during sleep between dominant and subordinate mice. Notably, single housing significantly increased rapid eye movement sleep (REMS) amount only in subordinate B6 mice, but not in subordinate F1 hybrids or dominant mice of either lines, suggesting a genetically modulated sensitivity to social conditions. Our findings suggest complicated interactions between social environment, social hierarchy, and genetic factors in REMS regulation.

Introduction

Numerous studies support the idea that social isolation and low socioeconomic status increase stress or susceptibility to stress1,2,3,4. Sleep is another factor that is related to stress in humans5,6,7. Mammalian sleep comprises rapid eye movement sleep (REMS) and non-REMS (NREMS). REMS is characterized by muscle atonia, hippocampal theta oscillations, and vivid dreaming, whereas NREMS is characterized by cortical slow-wave activity. Considering the bidirectional relationship between sleep and stress7, sleep may be a factor that links social environment or social hierarchy with health and quality of life.

The effects of social environment on sleep in humans or other social animals remain elusive. The presence of other individuals may lead to increased sensory stimuli and stress, resulting in reduced sleep quality, or to a sense of security, resulting in improved sleep quality. Most sleep studies using mice are conducted under single-housing conditions8,9,10,11. Like humans, however, mice are social animals, and long periods of social isolation result in depressive behaviors12, which may further affect sleep quality. Among cagemates, mice form a social hierarchy, and the social rank of each individual mouse can be measured with behavioral assays including agonistic behavioral analyses, limited-resource competition tests, the urine marking test, and the dominant tube test13,14,15,16,17. Numerous mouse studies have addressed the relationship between social rank and behavior or stress resilience15,17,18,19,20,21,22. These studies indicate a complicated relationship between social rank, genetic background, and health22, and conflicting conclusions have been drawn regarding the predictive ability of social rank on stress susceptibility19,20,21.

A few studies have compared mouse sleep between single-housing and group-housing conditions23,24,25. In these studies, group housing resulted in fragmentation or reduction of REMS and/or NREMS, and altered responses to sleep deprivation23,24,25. A study examining the relationship between social rank and sleep under group-housing conditions showed that higher social rank is associated with a higher REMS amount during the dark (active) phase and a lower REMS amount during the light (inactive) phase26. The combined effects of social condition (group housing vs. single housing) and social hierarchy (high rank vs. low rank) on sleep, however, remain unknown. Moreover, sleep is strongly disrupted by mechanical stimuli based on the fact that gentle handling is the major method for inducing sleep deprivation27. During social interactions, direct physical contact, such as allogrooming or physical attack, might cause immediate arousal. Indeed, a study in primates, i.e. wild olive baboons, reported that group-housing leads to fragmented sleep, likely due to increased physical contact28. In addition, under group-housing conditions, sleep might be affected by competition for limited resources such as space and nesting materials. Such a competition is suggested to reduce the REM sleep amount in horses29. Many of the previously reported effects of group housing on sleep can be explained by these factors, and these effects might mask various psychologic effects caused by the presence of cagemates. Thus, under group-housing conditions, sleep is affected both by direct physical contact and other social factors, complicating interpretation of the results. Here, we designed a neighbor-housing condition utilizing a large cage segregated into sections by partitions that preclude direct physical interaction but still allow interactions through visual, olfactory, or auditory cues and bedding exchange. We compared the sleep architecture of top-ranking (dominant) and low-ranking (subordinate) individuals under this neighbor-housing condition and under single-housing conditions.

The inbred mouse strain, C57BL/6J (B6), is the gold standard for neuroscience or sleep research. B6 mice, however, do not form robust dominant-subordinate hierarchies under certain conditions, i.e. when evaluated for by territorial behaviors between a pair of male adults unfamiliar to each other15. Thus, the lack of an effect of neighbor housing or social rank on sleep in B6 mice might be due to the weak social hierarchy of this strain. The outbred CD1 mice and CD1×B6 F1 hybrids form much more robust dominant-subordinate hierarchies when evaluated by the same assay15. Therefore, in this study, we evaluated two mouse lines, i.e., B6 mice and ICR×B6 F1 hybrids (ICR and CD1 are closely related albino mice; we used F1 hybrids, not the ICR mice, considering that the former likely has less genetic diversity). For each co-housed group, we determined the dominant and subordinate mice using the dominance tube test, a test that is fairly simple and robust and provides results correlated with those of other methods that assess social hierarchy in B6 and ICR mice21,30,31,32, and then measured their sleep architecture under the neighbor-housing and single-housing conditions.

Results

Determination of social rank in B6 and ICR×B6 F1 mice using the dominance tube test

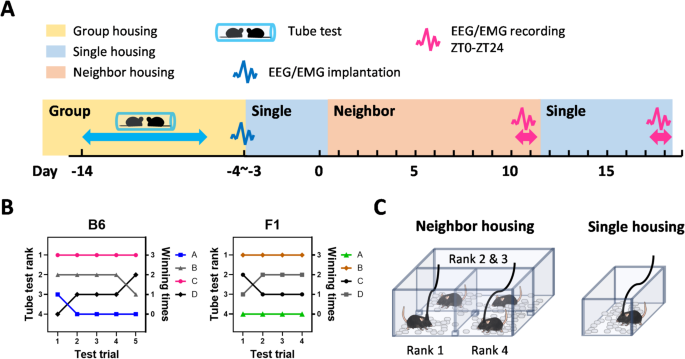

The experimental schedule is presented in Fig. 1A. The dominance tube test is an assay for measuring social hierarchy in mice16. We applied this test to B6 and ICR×B6 F1 mice housed in groups of four to determine the dominant mouse and the most subordinate mouse for each group (Fig. 1B). The detailed results of the test are shown in Table S1. During the dominance tube test, the test duration of time spent in the tube between subordinate mice and other mice was much shorter for ICR×B6 F1 mice (1.1 ± 0.3 s) than for B6 subordinate mice (2.2 ± 0.2 s; p = 0.0084, t-test). Although cautious interpretation is required, considering that the test duration is shorter when the rank distance increases16, our results might imply that social hierarchies are more robustly formed in ICR×B6 F1 mice compared to B6 mice, which is consistent with findings from another study addressing social hierarchy based on territorial behaviors15.

Determination of social rank and design of a neighbor-housing condition for measuring sleep in dominant and subordinate mice. A Experimental schedule presented as a timeline, illustrating the sequence of the dominance tube test, assignment to neighbor- or single-housing conditions, and sleep recording periods. B Typical example of the daily results of dominance tube test in B6 or ICR×B6 F1 mice. C Design of the sleep-recording arena for neighbor-housing and single-housing conditions.

Sleep measurements under neighbor-housing and single-housing conditions

To assess whether the sleep architecture is affected by differences in social rank, social environment, or mouse line, we designed a cage that was partitioned by acrylic boards into three sections (Fig. 1C). Dominant and subordinate mice were each placed in one of the sections, and the two middle-ranking mice were housed together in the remaining section (Fig. 1C). The partition was designed to preclude direct physical contact such as allogrooming or attacking while still allowing mice to visually recognize each other. Moreover, the gaps beneath and above the partitions allowed interaction through auditory and olfactory cues, and mice also frequently exchanged bedding materials via these gaps. The partitions also prevented cagemates from causing damage to the electrodes or cables for measuring electroencephalogram (EEG) and electromyogram (EMG) signals.

Following completion of the dominance tube test, the mice were acclimatized to the above cage with partitions and then underwent EEG/EMG recording for 24Â h to measure sleep/wake under the neighbor-housing condition. Subsequently, the dominant and subordinate mice were each acclimatized to a normal sleep-recording cage and underwent EEG/EMG recording for another 24Â h to measure sleep/wake under the single-housing condition.

B6 subordinate mice exhibited a large increase in REMS amount following transitioning to the single-housing condition

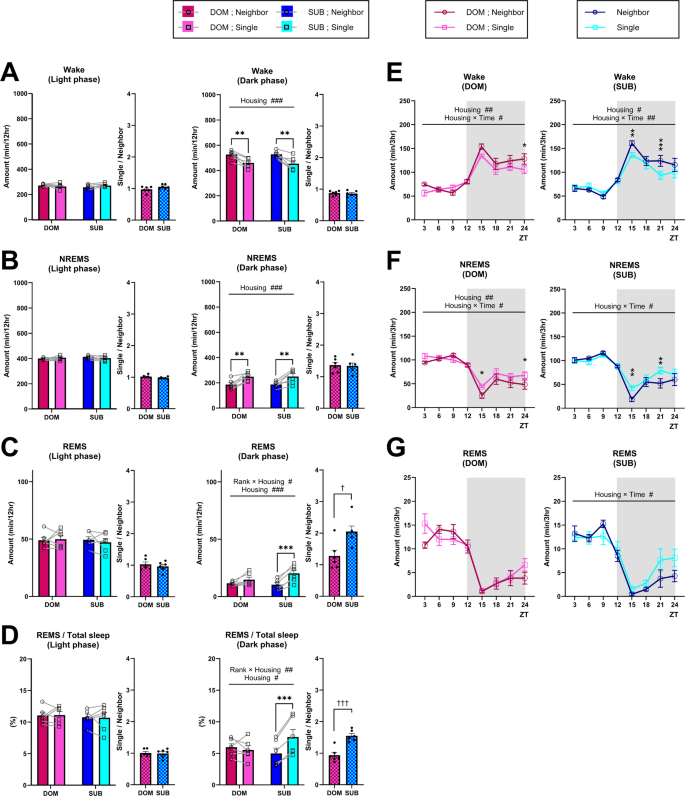

The sleep architecture in mammals refers to the cyclical transitions among vigilance states—wakefulness, REM sleep, and NREM sleep—and is quantitatively evaluated by measuring the total time spent in each state during the light and dark periods, the duration and number of individual epochs, and parameters such as the REM sleep cycle7,8,9. The sleep architecture of B6 dominant and subordinate mice under neighbor-housing and single-housing conditions are shown in Figs. 2 and S1. Under the neighbor-housing condition, we detected no significant difference in the sleep architecture between dominant and subordinate mice (Fig. 2A-D; Fig. S1A–H), suggesting that social hierarchy does not affect sleep architecture under our neighbor-housing condition in which direct physical contact is prevented. When dominant and subordinate mice were kept in the single-housing condition, regardless of the rank, the amount of wake decreased and, concomitantly, the amount of NREMS increased during the dark phase when compared to the neighbor-housing condition (Fig. 2A and B). The decreased wake amount could be attributed to the shortening of wake episode durations (Fig. S1D), whereas the increase in NREMS amount could be attributed to the increase in the NREMS episode numbers (Fig. S1B). Evaluation of changes in the amounts of each vigilance state every 3 h (Fig. 2E–G) revealed that the NREMS amount was lower at the beginning of the dark phase in the neighbor-housing condition compared to the single-housing condition for both dominant and subordinate mice (Fig. 2F), which might be due to active social interactions during the dark phase under the neighbor-housing condition.

B6 dominant and subordinate mice exhibited overall similar sleep architecture under the neighbor-housing condition, and transitioning to a single-housing condition largely increases the REMS amount, specifically in subordinate mice. (A–C) Total amount of wake (A), NREMS (B), and REMS (C) (light phase, dark phase) in dominant (DOM) and subordinate (SUB) mice under the neighbor-housing or single-housing condition. (D) Ratio of REMS amount to the total sleep amount (light phase, dark phase). Bar graphs represent the mean ± SEM. Each point represents an individual mouse. (E–F) Daily variation in wake (E), NREMS (F), and REMS (G) every 3 h. ZT zeitgeber time. Each point represents the mean ± SEM. #,*p < 0.05; ##,**p < 0.01; ###,***p < 0.001 (two-way repeated measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test); †p < 0.05; ††p < 0.01; †††p < 0.001 (unpaired t-test).

Notably, in the subordinate mice, both the amount of REMS and the ratio of the REMS amount to total sleep time during the dark phase were larger under the single-housing condition compared to the neighbor-housing condition (Fig. 2C and D). In contrast, for the dominant mice, no significant difference in the REMS amount was detected between housing conditions (Fig. 2C and D). For the subordinate mice, the REMS amount increase could be attributed to both the increased episode numbers and elongated episode durations (Fig. S1C,F). The REMS amount increase seemed to occur mainly in the latter half of the dark phase (Fig. 2G). In addition, for both dominant and subordinate mice, the REMS cycle was shorter in the single-housing condition compared to the neighbor-housing condition (Fig. S1H).

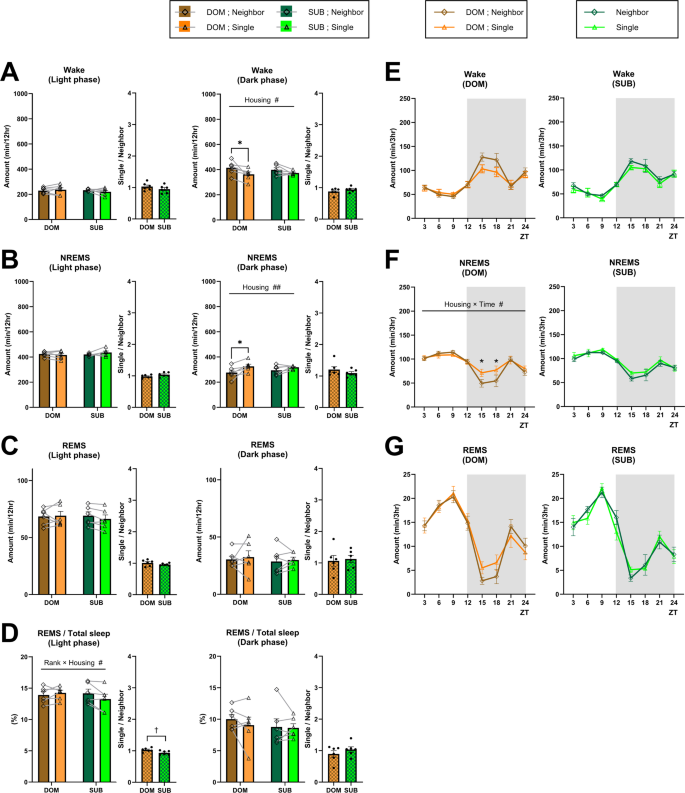

In ICR×B6 F1 mice, the effects of the housing conditions on REM sleep in the subordinate mice were abolished

The sleep architecture of ICR×B6 F1 dominant and subordinate mice under neighbor-housing and single-housing conditions are shown in Figs. 3 and S2. Similar to B6 mice, under the neighbor-housing condition, the sleep architecture was not significantly different between dominant and subordinate mice, except for the REMS latency, which was shorter in the subordinate mice (Fig. S2G). When dominant and subordinate mice were kept in a single-housing condition, the amount of wake decreased and the amount of NREMS increased during the dark phase compared to the neighbor-housing condition, similar to observations in B6 mice (Fig. 3A and B). The effect seemed weaker, though, and limited to dominant mice. Neither the episode numbers nor the episode durations of wake and NREMS were significantly affected (Fig. S2A,B,D,E), making it difficult to attribute changes in wake and NREMS amount to a specific factor. When we examined changes in the amounts of each vigilance state every 3 h (Fig. 3E–G), the NREMS amount was lower in dominant mice at the first half of the dark phase in the neighbor-housing condition compared to the single-housing condition (Fig. 3F).

ICR×B6 F1 dominant and subordinate mice exhibited an overall similar sleep architecture under the neighbor-housing condition, and transition to the single-housing condition does not affect the REMS amount. (A–C) Total amount of wake (A), NREMS (B), and REMS (C) (light phase, dark phase) in dominant (DOM) and subordinate (SUB) mice under the neighbor-housing or single-housing condition. (D) Ratio of the REMS amount to the total sleep amount (light phase, dark phase). Bar graphs represent the mean ± SEM. Each point represents an individual mouse. (E–F) Daily variation in wake (E), NREMS (F), and REMS (G) every 3 h. ZT zeitgeber time. Each point represents the mean ± SEM. #,*p < 0.05; ##,**p < 0.01 (two-way repeated measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test); †p < 0.05 (unpaired t-test).

Notably, in striking contrast to B6 subordinate mice, in the ICR×B6 F1 subordinate mice, neither the amount of REMS nor the ratio of the REMS amount to total sleep time during the dark phase was significantly affected by the housing condition (Fig. 3C,D). Concomitantly, the REMS episode numbers and episode durations were also not significantly affected (Fig. S2C,F). In addition, in contrast to B6 mice, for both dominant and subordinate ICR×B6 F1 mice, the REMS cycle was not significantly affected by housing conditions (Fig. S2H).

ICR×B6 F1 mice exhibited higher REMS amount compared to B6 mice, but this difference was suppressed in single-housed subordinate mice

We also compared the amounts of wakefulness, NREMS, and REMS between B6 mice and ICR×B6 F1 mice under various conditions (Fig. 4). Overall, ICR×B6 F1 mice exhibited a lower wake amount and a higher NREMS amount compared to B6 mice (Fig. 4A,B). Notably, regarding the REMS amount and the ratio of REMS amount to total sleep time, in dominant mice, these values were overall higher in ICR×B6 F1 mice compared to B6 mice; in subordinate mice, however, the difference was suppressed under the single-housing condition during the dark phase (Fig. 4C,D).

ICR×B6 F1 mice exhibited an overall higher REMS amount and REMS ratio compared to B6 mice, but this difference was suppressed in subordinate mice under the single-housing condition. (A–D) Comparison of the total amount of wake (A), NREMS (B), and REMS (C), as well as the ratio of REMS to the total sleep amount (D), between B6 mice and ICR×B6 F1 mice during the light phase and dark phase in dominant (DOM) and subordinate (SUB) mice under neighbor-housing or single-housing conditions. (E) Coincident rate of vigilance states between dominant and subordinate mice (light phase, dark phase). Bar graphs represent the mean ± SEM. Each point represents an individual mouse. #,*p < 0.05; ##,**p < 0.01; ###,***p < 0.001; ####,****p < 0.0001 (two-way repeated measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test).

We also examined the coincidence rate of vigilance states between dominant and subordinate mice (Fig. 4E). During the dark phase, the coincidence rate was higher under the neighbor-housing condition compared to the single-housing condition, supporting that social interactions occur even when direct physical contact is mostly precluded. In addition, the coincidence rate during the dark phase was higher in B6 mice compared to ICR×B6 F1 mice, suggesting that the sleep architecture of cagemates tends to synchronize more in B6 mice.

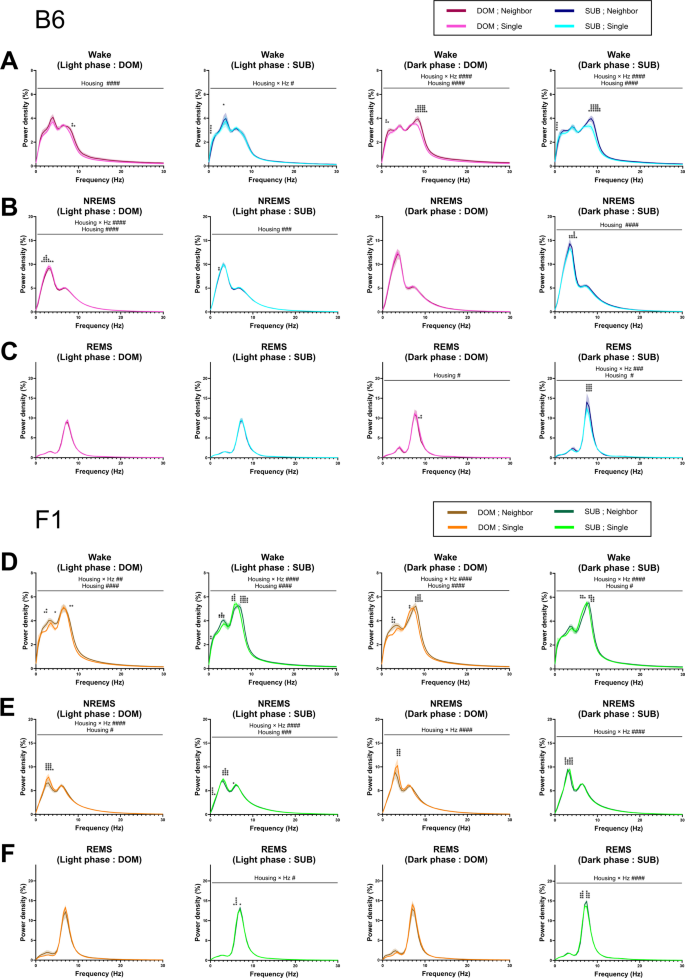

Housing conditions differently affected EEG power spectra of dominant and subordinate mice in both mouse lines

We next examined the EEG power spectra of B6 mice during each vigilance state (Fig. 5A–C). In dominant mice, the NREMS EEG power in the delta range (0.5–4.0 Hz) was higher under the single-housing condition compared to the neighbor-housing condition during the light phase (Fig. 5B). Similarly, the REMS EEG power in the theta range (6.0–10.0 Hz) was higher under the single-housing condition compared to the neighbor-housing condition (Fig. 5C). In contrast, in the case of subordinate mice, we did not detect a clear effect of the housing condition on the NREMS EEG delta power (Fig. 5B), and REMS EEG theta power was lower in the dark phase under the single-housing condition (Fig. 5C).

Transition from the neighbor-housing condition to single-housing conditions has different effects on EEG power between dominant mice and subordinate mice of both lines. (A–C) EEG power spectra of B6 mice during wake (A), NREMS (B), and REMS (C) (light phase (dominant, subordinate) and dark phase (dominant, subordinate). (D–F) EEG power spectra of ICR×B6 F1 mice during wake (A), NREMS (B), and REMS (C) (light phase (dominant, subordinate) and dark phase (dominant, subordinate). Data represent mean ± SEM. #,*p < 0.05; ##,**p < 0.01; ###,***p < 0.001; ####,****p < 0.0001 (two-way repeated measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test).

When we examined the EEG power spectra of ICR×B6 F1 mice during each vigilance state (Fig. 5D–F), we observed a similar trend, i.e. in dominant mice, the NREMS EEG delta power was higher under the single-housing condition compared to the neighbor-housing condition (Fig. 5E), whereas in subordinate mice, REMS EEG theta power was lower under the single-housing condition compared to the neighbor-housing condition (Fig. 5F). In addition, in subordinate mice, NREMS EEG delta power was slightly but significantly different between the single-housing and neighbor-housing conditions, which appeared to be due to a slight shift in the peak frequency (Fig. 5E).

Discussion

Dominant and subordinate mice exhibited an overall similar sleep architecture under the neighbor-housing condition regardless of the genetic background

Under our neighbor-housing conditions, we detected no significant difference in sleep architecture between dominant and subordinate mice of either line. This finding largely contrasts with that of a previous mouse study assessing the effect of social rank on sleep under group-housing conditions, which showed that higher social rank is associated with a lower REMS amount in the light phase and a higher REMS amount in the dark phase26. This difference suggests that the previously observed effects of social rank on REMS arise from direct physical contact, which is mostly precluded in our neighbor-housing condition. In horses who are group-housed under limited space, only the high-ranking individuals can sleep in recumbency, which is required for REMS, whereas this association with social rank is resolved under conditions with sufficient space29. In the case of group-housed mice, perhaps some antagonistic physical contact between dominant and subordinate mice during the dark phase leads to stress in subordinate mice, which can acutely reduce REMS33, resulting in a subsequent rebound during the light inactive phase. Another possibility is that, under our neighbor-housing condition, mice were basically unaware of their cagemates. We would argue against the latter possibility, however, for the following reasons. First, the coincidence rate of the vigilance states between dominant and subordinate mice was higher under the neighbor-housing condition than in the single-housing condition, which is difficult to explain without assuming any social interaction. Second, as further discussed below, both dominant and subordinate mice exhibited a different sleep architecture under the single-housing condition compared to the neighbor-housing condition, indicating that the two conditions are not equivalent for mice. Third, a previous study that compared the effect of housing conditions between group housing, neighbor housing, and single housing on behavior revealed that mice kept under the neighbor-housing condition exhibited levels of anxiety and cognitive abilities comparable to those of mice kept under a group housing condition but distinct from those of mice kept under a single-housing condition34. In that study, similar to our study, cages for neighbor housing were designed to allow for visual, olfactory, and auditory interactions while limiting direct contact between mice. Thus, much of the effects of social interaction seem not to require direct contact.

Another possibility is that differences in the mouse lines used between the previous group-housing study and the current neighbor-housing study resulted in the contrasting effects of social rank on sleep. In the previous study, ICR mice were tested, whereas in the present study, B6 and ICR×B6 F1 mice were tested. Indeed, under specific conditions, social hierarchy is more robustly formed in CD1 mice compared to B6 mice15, and CD1 mice and ICR mice are closely related mice. Importantly, however, the same study concluded that social hierarchy is robustly formed in CD1×B6 F1 mice15. In the tube test in our study, although cautious interpretation is necessary, the time spent in the tube was shorter for subordinate ICR×B6 F1 mice compared to subordinate B6 mice, which might further support that the social hierarchy is more robust in ICR×B6 F1 mice. Nevertheless, we detected almost no difference in the sleep architecture between dominant and subordinate mice in neighbor-housed ICR×B6 F1 mice, even though their sleep architecture largely differed from that of B6 mice, indicating that sleep architecture under our neighbor-housing condition is unaffected by social rank, regardless of mouse line.

NREMS amount was higher under the single-housing condition compared to the neighbor-housing condition regardless of social rank or mouse line

For both dominant and subordinate mice, the NREMS amount during the dark phase was higher under the single-housing condition compared with the neighbor-housing condition, and the wake amount was concomitantly lower, regardless of the mouse line. This might be explained by higher arousal levels during the dark phase in the neighbor-housing condition due to social interaction. Consistently, when we examined the wake EEG power spectra during the dark phase, theta power was higher under the neighbor-housing condition compared with the single-housing condition (Fig. 5A,D), perhaps reflecting enhanced arousal.

Combined effects of social rank and housing condition on sleep EEG power spectra are observed in both mouse lines

The housing condition differentially affected dominant mice and subordinate mice. In particular, social rank-dependent effects on sleep EEG power spectra were observed in both B6 mice and ICR×B6 F1 mice. In dominant mice of both lines, NREMS EEG delta power during the light phase was consistently higher under the single-housing condition compared to the neighbor-housing condition. In dominant B6 mice, REMS EEG theta power was higher under the single-housing condition compared to the neighbor-housing condition. In contrast, for subordinate mice of both lines, REMS EEG theta power during the dark phase was lower under the single-housing condition. NREMS EEG delta power reflects cortical slow wave activity, which is crucial for memory consolidation and hormone regulation35,36, whereas REMS EEG theta power reflects hippocampal theta oscillation, which is also crucial for memory consolidation37 and is positively correlated with the upsurge of cortical blood flow during REMS38. Thus, these EEG variables reflect sleep quality, and both NREMS delta power and REMS theta power are reduced by chronic stress33. Based on our results, we speculate that single housing has two opposing effects on sleep, i.e., improvement of sleep quality due to undisturbed sleep and worsening of sleep quality due to social isolation stress, and the balance of the two opposing effects is affected by social rank. From this point of view, it might be said that, for dominant mice, sleep quality was better under single-housing conditions compared to neighbor-housing conditions because the effect of undisturbed sleep was larger, whereas for subordinate mice, sleep quality was worse under single-housing conditions because the effect of social isolation stress was larger. This notion is consistent with findings from many previous studies demonstrating that lower social rank is associated with higher stress susceptibility21,22.

REMS amount was higher under the single-housing condition compared to the neighbor-housing condition only in subordinate B6 mice

We also found that housing conditions have differential effects among dominant and subordinate mice that are largely dependent on the mouse line. In B6 subordinate mice, but not B6 dominant mice, the single-housing condition led to a large increase in the REMS amount during the dark phase. Notably, for ICR×B6 F1 subordinate mice, this effect on REMS amount was not observed. As discussed above, social hierarchy seemed to be more robustly formed in ICR×B6 F1 mice compared to B6 mice, although cautious interpretation is necessary. Then, the finding that social rank impacts sleep more in B6 mice than in ICR×B6 F1 mice might be an unexpected result. Nevertheless, the coincidence rate of vigilance states between dominant and subordinate mice was higher in B6 mice compared to ICR×B6 F1 mice, which suggests that B6 mouse sleep is more sensitive to the social environment.

It is difficult to explain why the REMS amount was higher under the single-housing condition, specifically in B6 subordinate mice. Importantly, the baseline REMS amount was overall higher in ICR×B6 F1 mice compared to B6 mice, and this difference was suppressed under the single-housing condition in subordinate mice. Thus, perhaps some REMS-promoting factors are constitutively active in ICR×B6 F1 mice, whereas they are regulated in a social environment- and social rank-dependent manner in B6 mice. Addressing the genetic differences between the two lines might be beneficial for further narrowing down the causal genes. The central REM sleep circuit is located in the brainstem pons and medulla9, and such factors might act on these circuits either cell autonomously or non-autonomously. Although evidence support that REMS might be beneficial for maintaining brain functions7,38, we cannot conclude that single housing is beneficial for subordinate individuals in terms of sleep. As discussed above, overall sleep quality remained relatively low under the single-housing condition, and our study examined its effects only during a relatively early phase.

Limitations of the study

While there are various assays to address social hierarchy in mice13,14,15,16, we only employed the dominance tube test. Although this test is simple and provides robust results, and there are studies that have shown that the rankings obtained with this method well correlate with those of other assays in case of B6 or ICR mice21,30,31,32, it is not always the case for all mouse lines13 and thus cautious interpretation is required. Another limitation is the small sample size (6 mice per each experimental group), although it is quite a typical sample size for sleep studies39,40. Finally, only male mice were used in this study. While both male and female group-housed mice develop social hierarchies, the male social hierarchies arise from and lead to more antagonistic interactions than the female hierarchies, suggesting qualitative differences in social hierarchies among sexes41. Moreover, for some aspects of behavioral outcomes following stress exposure, social rank can have opposing effects on males and females18. Thus, additional studies investigating potential sex differences in sleep changes related to housing conditions and social hierarchy are necessary.

Conclusion

This study revealed mixed effects of social environment, social rank, and mouse line on sleep in male mice. In particular, these factors significantly affected the amount and quality of REM sleep in a combined manner. In contrast to previous studies that measured sleep under group-housing conditions, the design of the neighbor-housing condition in the present study minimized the effect of direct physical contact, which can disturb sleep. The findings of the present study have implications for the future design of sleep studies using mice. Moreover, our findings on the interplay between the REMS amount, social hierarchy, and social isolation provide novel insight into the mechanisms underlying REMS. Future studies exploring the function of REMS, which remains largely unknown, may further deepen our understanding.

Methods

Animals

C57BL/6JJcl mice and Jcl: ICR mice were purchased from Japan SLC Inc. (Shizuoka, Japan) and Clea Japan (Tokyo, Japan). ICR×B6 F1 mice were obtained by mating male C57BL/6JJcl mice and female Jcl: ICR mice. The mice were group housed under a 12/12 h light/dark cycle (lights on at 8:30 am) at a controlled temperature (21.0 ± 2.0 °C) with free access to water and food. Male mice were used for all behavioral tests and sleep measurements.

Dominance tube test

The dominance tube test was performed as previously described with some modifications16. Male mice approximately 4 weeks of age were divided into groups of 4 and group housed. At the age of 8 to 9 weeks, the mice underwent behavioral testing during the light phase. Prior to the tests, mice were gently handled by the same experimenter and acclimatized to the behavioral setting for two consecutive days. During the behavioral test, the room temperature was maintained at 21.5 °C and illumination in the room was kept at 40 lx. Briefly, in the tube test, two cagemate mice were gently urged to enter a narrow plastic tube (34 mm diameter and 30 cm long for B6 mice and 39 mm diameter and 30 cm long for ICR×B6 F1 mice) from opposite ends and meet in the middle. When one of the mice retreated out of the tube, that mouse was designated as the subordinate mouse. For each pair of the six combinations, the tube test was conducted once a day. In this study, as we only needed to determine the top-ranking (dominant) and bottom-ranking (subordinate) individuals rather than determining the ranks of all four individuals, we terminated the dominance tube test once the dominant and subordinate individuals were consistently identified after four consecutive trials. For each mouse line, 9 groups of mice were subjected to the dominance tube test, and the 6 groups that completed the test earliest were selected for subsequent sleep recordings. We measured the body weight of all mice before the tube test (table S1) and confirmed that the difference in body weight among cagemates is within the recommended range of 2 ~ 15%16. In addition, we detected no significant difference in body weight between dominant and subordinate mice (main effect of rank p = 0.2033, main effect of line p < 0.0001, interaction p = 0.3857, two-way ANOVA).

Sleep recording

Sleep recording was performed following the procedures described previously42, and the following text partially reproduces that description. Under isoflurane anesthesia, mice were implanted with EEG/EMG electrodes. Stainless steel EEG electrodes were implanted epidurally over the parietal cortex (3 mm posterior to bregma, 1.5 mm lateral to the midline) and cerebellum (6.5 mm posterior to bregma, 2 mm lateral to the midline), and EMG electrodes were embedded into the trapezius muscles bilaterally. Mice were allowed to recover from surgery under the single-housing condition for 3 to 4 days. Subsequently, mice were placed in the neighbor-housing condition, which was a large cage (W: 36 cm, D: 28 cm, HL: 25 cm) divided into three sections by partitions made of acrylic boards (Fig. 1C). The acrylic boards were elevated 8 mm from the floor to allow for the exchange of bedding materials. Dominant and subordinate mice were each connected to the EEG/EMG recording cable. The cable was connected to a commutator, allowing mice to move freely within its section. After being housed under this neighbor-housing condition for 10 days, EEG/EMG signals were recorded for 24 h. Subsequently, dominant and subordinate mice were transferred to standard sleep-recording chambers with EEG/EMG cables connected to a commutator for the single-housing EEG/EMG recording. After being kept under this condition for 6 days, EEG and EMG signals were recorded for 24 h.

Under each condition, EEG/EMG signals were recorded from the onset of the light phase for 24 h. EEG/EMG signals were band-pass filtered at 0.5–128 Hz, collected, and digitized at a sampling rate of 256 Hz using VitalRecorder (Kissei Comtec, Nagano, Japan). The EEG signals were divided into 4-s epochs, subjected to fast Fourier transform, and further analyzed using SleepSign (Kissei Comtec). The vigilance state in each epoch was manually classified as REMS, NREMS, or wake based on the EEG patterns, the absolute delta (0.5–4 Hz) power, the theta (6–10 Hz) power to delta power ratio, and the integral of the EMG signals. Epochs with high EMG and low delta power were classified as wake, epochs with high delta power and low EMG were classified as NREMS, and epochs with even lower EMG (suggestive of muscle atonia) and a high theta power to delta power ratio were classified as REMS. If a single epoch contained multiple states, the predominant state was assigned. Epochs that contained presumable large movement-derived artifacts in the EEG data were included in the stage analysis but were excluded from the EEG power spectrum analysis. When calculating the EEG power spectrum of wake, NREMS, or REMS, the EEG power of each frequency bin was expressed as a percentage of the mean total EEG power over all frequency bins (1–30 Hz) across 24 h. All scoring was performed by an experimenter blinded to the experimental groups. REMS latency was defined as the average duration of the NREMS episode immediately prior to each REMS episode, and the REMS cycle was defined as the average time from the onset of a REMS epoch to the onset of the next REMS epoch. The coincidence rate of vigilance states between dominant and subordinate mice was calculated by the following formula:

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using PRISM 10 (GraphPad Software, Boston, MA, USA), and statistical significance was set at p = 0.05. Bar graphs and line graphs represent mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Where applicable, all tests were two-tailed.

Data availability

All raw data analyzed in this paper have been deposited at Mendeley (Mendeley Data: https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/2y22nbkxw5/1) and are publicly available as of the date of publication. Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon reasonable request. This paper did not report original code.

References

-

Vitale, E. M. & Smith, A. S. Neurobiology of loneliness, isolation, and loss: Integrating human and animal perspectives. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 16, 846315. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2022.846315 (2022).

-

Ahmed, M., Cerda, I. & Maloof, M. Breaking the vicious cycle: The interplay between loneliness, metabolic illness, and mental health. Front. Psychiatry. 14, 1134865. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1134865 (2023).

-

Kraft, P. & Kraft, B. Explaining socioeconomic disparities in health behaviours: A review of biopsychological pathways involving stress and inflammation. Neurosci. Biobehav Rev. 127, 689–708. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.05.019 (2021).

-

Johnson, S. et al. Environmental, and psychosocial influences on resilience toward chronic stress. Cureus 16, e67897. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.67897 (2024).

-

Yu, X., Nollet, M., Franks, N. P. & Wisden, W. Sleep and the recovery from stress. Neuron 113, 2910–2926. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2025.04.028 (2025).

-

Broderick, M. L., Khan, Q. & Moradikor, N. Understanding the connection between stress and sleep: from underlying mechanisms to therapeutic solutions. Prog Brain Res. 291, 137–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.pbr.2025.01.016 (2025).

-

Yasugaki, S., Okamura, H., Kaneko, A. & Hayashi, Y. Bidirectional relationship between sleep and depression. Neurosci. Res. 211, 57–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neures.2023.04.006 (2025).

-

Hayashi, Y. et al. Cells of a common developmental origin regulate REM/non-REM sleep and wakefulness in mice. Science 350, 957–961. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aad1023 (2015).

-

Kashiwagi, M. et al. A pontine-medullary loop crucial for REM sleep and its deficit in Parkinson’s disease. Cell 187, 6272–6289 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2024.08.046

-

Funato, H. et al. Forward-genetics analysis of sleep in randomly mutagenized mice. Nature 539, 378–383. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature20142 (2016).

-

Li, S. B. et al. Hyperexcitable arousal circuits drive sleep instability during aging. Science 375, eabh3021. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abh3021 (2022).

-

Ieraci, A., Mallei, A. & Popoli, M. Social isolation stress induces anxious-depressive-like behavior and alterations of neuroplasticity-related genes in adult male mice. Neural Plast. 2016 (6212983). https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/6212983 (2016).

-

Fulenwider, H. D., Caruso, M. A. & Ryabinin, A. E. Manifestations of domination: assessments of social dominance in rodents. Genes Brain Behav. 21, e12731. https://doi.org/10.1111/gbb.12731 (2022).

-

Varholick, J. A., Bailoo, J. D., Jenkins, A., Voelkl, B. & Würbel, H. A. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the relationship between social dominance status and common behavioral phenotypes in male laboratory mice. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 14, 624036. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2020.624036 (2020).

-

Battivelli, D. et al. Induction of territorial dominance and subordination behaviors in laboratory mice. Sci. Rep. 14, 28655. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75545-4 (2024).

-

Fan, Z. et al. Using the tube test to measure social hierarchy in mice. Nat. Protoc. 14, 819–831. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41596-018-0116-4 (2019).

-

Horii, Y. et al. Hierarchy in the home cage affects behaviour and gene expression in group-housed C57BL/6 male mice. Sci. Rep. 7, 6991. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-07233-5 (2017).

-

Karamihalev, S. et al. Social dominance mediates behavioral adaptation to chronic stress in a sex-specific manner. Elife 9 https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.58723 (2020).

-

LeClair, K. B. et al. Individual history of winning and hierarchy landscape influence stress susceptibility in mice. Elife 10 https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.71401 (2021).

-

Šabanović, M., Liu, H., Mlambo, V., Aqel, H. & Chaudhury, D. What it takes to be at the top: The interrelationship between chronic social stress and social dominance. Brain Behav. 10, e01896. https://doi.org/10.1002/brb3.1896 (2020).

-

Larrieu, T. et al. Hierarchical status predicts behavioral vulnerability and nucleus accumbens metabolic profile following chronic social defeat stress. Curr. Biol. 27, 2202–2210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2017.06.027 (2017). .e2204.

-

Razzoli, M., Nyuyki-Dufe, K., Chen, B. H. & Bartolomucci, A. Contextual modifiers of healthspan, lifespan, and epigenome in mice under chronic social stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 120, e2211755120. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2211755120 (2023).

-

Febinger, H. Y., George, A., Priestley, J., Toth, L. A. & Opp, M. R. Effects of housing condition and cage change on characteristics of sleep in mice. J. Am. Assoc. Lab. Anim. Sci. 53, 29–37 (2014).

-

Kaushal, N., Nair, D., Gozal, D. & Ramesh, V. Socially isolated mice exhibit a blunted homeostatic sleep response to acute sleep deprivation compared to socially paired mice. Brain Res. 1454, 65–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2012.03.019 (2012).

-

Sotelo, M. I. et al. Neurophysiological and behavioral synchronization in group-living and sleeping mice. Curr. Biol. 34, 132–146e135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2023.11.065 (2024).

-

Karamihalev, S., Flachskamm, C., Eren, N., Kimura, M. & Chen, A. Social context and dominance status contribute to sleep patterns and quality in groups of freely-moving mice. Sci. Rep. 9, 15190. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-51375-7 (2019).

-

Suzuki, A., Sinton, C. M., Greene, R. W. & Yanagisawa, M. Behavioral and biochemical dissociation of arousal and homeostatic sleep need influenced by prior wakeful experience in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 110, 10288–10293. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1308295110 (2013).

-

Loftus, J. C. et al. Sharing sleeping sites disrupts sleep but catalyses social tolerance and coordination between groups. Proc. Biol. Sci. 291, 20241330. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2024.1330 (2024).

-

Burla, J. B. et al. Space allowance of the littered area affects lying behavior in group-housed horses. Front. Vet. Sci. 4, 23. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2017.00023 (2017).

-

Wang, F. et al. Bidirectional control of social hierarchy by synaptic efficacy in medial prefrontal cortex. Science 334, 693–697. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1209951 (2011).

-

Sugimoto, H., Ikeda, K. & Kawakami, K. Atp1a3-deficient heterozygous mice show lower rank in the hierarchy and altered social behavior. Genes Brain Behav. 17, e12435. https://doi.org/10.1111/gbb.12435 (2018).

-

Lee, Y. A. & Goto, Y. The roles of serotonin in decision-making under social group conditions. Sci. Rep. 8, 10704. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-29055-9 (2018).

-

Yasugaki, S. et al. Effects of 3 weeks of water immersion and restraint stress on sleep in mice. Front. Neurosci. 13, 1072. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2019.01072 (2019).

-

Pais, A. B. et al. A novel neighbor housing environment enhances social interaction and rescues cognitive deficits from social isolation in adolescence. Brain Sci. 9 https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci9120336 (2019).

-

Marshall, L., Helgadóttir, H., Mölle, M. & Born, J. Boosting slow oscillations during sleep potentiates memory. Nature 444, 610–613. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature05278 (2006).

-

Besedovsky, L. et al. Auditory closed-loop stimulation of EEG slow oscillations strengthens sleep and signs of its immune-supportive function. Nat Commun 8 (1984). (2017) https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-02170-3

-

Boyce, R., Glasgow, S. D., Williams, S. & Adamantidis, A. Causal evidence for the role of REM sleep theta rhythm in contextual memory consolidation. Science 352, 812–816. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aad5252 (2016).

-

Tsai, C. J. et al. Cerebral capillary blood flow upsurge during REM sleep is mediated by A2a receptors. Cell. Rep. 36, 109558. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109558 (2021).

-

Tseng, Y. T. et al. The subthalamic corticotropin-releasing hormone neurons mediate adaptive REM-sleep responses to threat. Neuron 110, 1223–1239e1228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2021.12.033 (2022).

-

Yu, X. et al. A specific circuit in the midbrain detects stress and induces restorative sleep. Science 377, 63–72. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abn0853 (2022).

-

van den Berg, W. E., Lamballais, S. & Kushner, S. A. Sex-specific mechanism of social hierarchy in mice. Neuropsychopharmacology 40, 1364–1372. https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2014.319 (2015).

-

Hayashi, N. et al. Dynamic changes in sleep architecture in a mouse model of acute kidney injury transitioning to chronic kidney disease. Front. Neurosci. 19, 1581494. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2025.1581494 (2025).

Funding

This work was supported by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI grants JP22K21351, JP24K02116, JP24K21998, JP25H01717; MEXT World Premier International Research Center Initiative, and Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) grants JP24zf0127011, JP21wm0425018, and JP21zf0127005 (to Y.H.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, N.H., A.K., and Y.H.; methodology, N.H., A.K., and Y.H.; investigation, N.H., A.K., and Y.H.; data analysis, N.H. and Y.H.; project administration, Y.H.; supervision, Y.H.; writing original draft, N.H. and Y.H.; writing—review and editing Y.H.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

All mouse-related procedures and methods were approved by the institutional animal care and use committee of the Kyoto University Graduate School of Medicine (Permit no. MedKyo22091) and were conducted in accordance with its guidelines for the ethical treatment of animals. Mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation, with all efforts made to minimize potential discomfort or distress. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines (https://arriveguidelines.org).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hayashi, N., Kawai, A. & Hayashi, Y. Social rank and social environment combinedly affect REM sleep in mice.

Sci Rep 16, 871 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32402-2

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

Version of record:

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32402-2

Keywords

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post