South Africa Becomes the First African Country to Partially Legalize Cannabis

December 22, 2024

Durban, South Africa — On May 28, 2024 South Africa made history by becoming the first African nation to formally legalize recreational cannabis drug use. The Cannabis for Private Purposes Bill — otherwise abbreviated as “CfPPA” — was signed into law by President Cyril Ramaphosa less than a day before the historic 2024 South African General Elections which saw his party lose its 30 year control over Parliament.

Cannabis refers to a flowering plant, originating from the Asian continent, that has been cultivated and used by humans for thousands of years for medicinal, religious and recreational purposes. The drug originating from the flower of the cannabis plant is most commonly referred to in South Africa as “dagga” while in the U.S it’s more commonly known as “weed.”

This new bill now essentially means that private citizens can no longer be prosecuted for growing and consuming a limited amount of cannabis for recreational purposes — so long as it is grown and/or consumed within the confines of their own private property.

Those convicted of cannabis possession or dealing should have their records automatically expunged, though the ultimate fate of the estimated 3,000 prisoners currently in prison for cannabis-related offenses is currently unknown.

The bill’s signing is the final result of a decades-long Constitutional challenge, originally brought forward by pro-cannabis advocates in 1998. 20 years later in 2018, the Constitutional Court made its final ruling effectively legalizing the possession of cannabis for medical purposes. Recreational cannabis use was also subsequently legalized — subject to certain controversial restrictions — though the sale of recreational cannabis remains banned.

Since the 2018 Constitutional Court ruling, a growing number of cannabis clubs and dispensaries have been popping up around the country doing just that, either in ignorance or general disregard for the law. Many of these relatively new businesses offer a wide range of products at affordable prices, but are legally restricted to selling the psychoactive drug only to those who’ve been given a prescription by a doctor.

In reality, it’s well known within the cannabis community that virtually anyone with the required funds can walk into a dispensary and walk out with a near limitless amount of whatever product they choose — with, or without, a prescription. The seeming lack of enforcement around this is due to a number of factors including general confusion about what the new cannabis law actually allows and what it doesn’t.

| What South Africa’s new cannabis law allows | What it doesn’t allow |

| May grow and consume up to 600 grams (21.2 oz) of any kind of cannabis, in “private spaces,” 1200 grams (42 oz) per household | May not use any kind of cannabis in public spaces |

| May obtain license to sell cannabis for medical and or industrial use | May not sell or distribute cannabis for recreational purposes |

| May carry/transport up to 100 grams (3.5 oz) of cannabis in public spaces | May not drive and smoke cannabis |

Negative stereotypes traditionally associated with the plant have also been on the decline, as more scientific research and evidence is published documenting its effectiveness in treating a number of serious medical illnesses. This combined with the economic value of an industry already estimated to be worth eight figures has led to a thriving medical and recreational market.

But while South Africa’s pro-cannabis movement has ample reason to celebrate a monumental win, the new laws are not without their critics and complications. Such critics include both those who believe cannabis shouldn’t be legal under any circumstances, to those who argue it doesn’t go far enough in protecting the rights of individual cannabis growers.

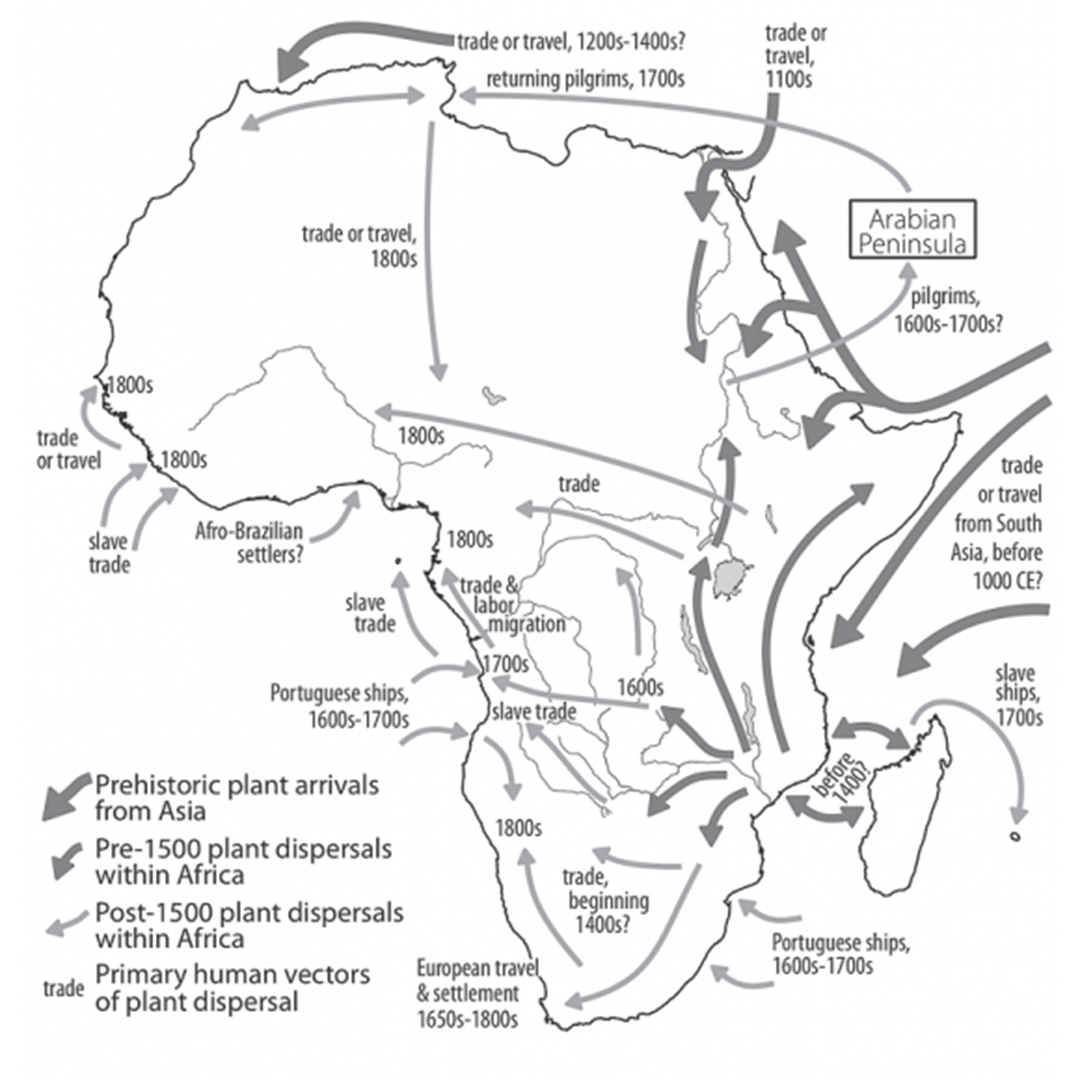

Still, the cannabis industry in South Africa continues to receive large amounts of government and private investment as many seek to profit from the lucrative and rapidly growing trade. Indeed, southern Africa has been a fertile ground for cannabis cultivation ever since the plant came to the continent some 1,000 years ago.

Historical Origins and Use of ‘Dagga’ on the African Continent

Historical evidence suggests that cannabis was originally imported from its native homeland in Asia. into Africa via the extensive early trade networks that persist to this day between the two continents. It is believed that cannabis first made contact with Africa via the island of Madagascar and the Mediterranean coast, before penetrating deeper into Africa’s interior.

The indigenous Khoisan and Bantu are the first known peoples in southern Africa to use the plant for recreational, medicinal and perhaps even spiritual purposes as far back as the 17th century. With the arrival of European colonists and traders to the area — initially the Dutch and later the English — they began to acquire and cultivate cannabis in large amounts for trade with the local Khoisan.

The colonists would further attempt to monopolize the cannabis trade in the region as they had done with a variety of other drugs in other locations around the world — including heroin, alcohol and tobacco. They were unsuccessful in those efforts primarily due to the fact that cannabis grows very easily, and was therefore in plentiful supply within the region. This particular area of southern Africa where cannabis is especially well suited to cultivation is known as the “dagga belt.”

Colonists still found value in cannabis for its usefulness as a trade commodity with the locals. It was also used as a form of payment and coercion in order to guarantee the natives would continue working on colonial plantations, as explained by British merchant George Thompson:

“[…] it is, therefore, the more extraordinary, that the whites, who seldom use the [cannabis] themselves, should cultivate it for their servants. But it is, I believe, as an inducement to retain the wild [Khoisan] in their service, whom they have made captives at an early age […] most of these people being extremely addicted to the smoking of [cannabis].”

George Thompson

By the early 19th century, however, the colonists’ attitude towards the cannabis trade began to sour. It was during this time that racist tropes began to proliferate around the concept of “dagga insanity” — similar to “reefer madness” in the U.S.

This viewpoint is reflected in the thesis of C.J.G. Bourhill titled “The Smoking of Dagga (Indian Hemp) among the Native Races of South Africa, and the Resultant Evils,” which analyzed conditions he witnessed while stationed at the Pretoria Lunatic Asylum:

“Leave a raw savage in his primitive state, leading his own life, let him smoke dagga, when and how he pleases, and it will be found that little or no harm will result. But take a young adult native, with his stunted mental powers, place him in abnormal surroundings, educate him beyond his intellectual capacity, give him hard and unnatural work to perform, let him become ambitious to copy the white man, and outshine his fellows. He then realizes the struggle for existence. Now introduce the vices, Alcohol, Dagga, unnatural sexual practices, etc. what is the result? The interactions of environment and vice proves too much for many; and the feebler brains drop out of the fight – shattered and broken.“

Bourhill’s racist ideas become the basis for the growing anti-cannabis sentiment within colonial South Africa. Said colonists were especially concerned with the effects of cannabis on the indigenous African, and later the Indian population that was transplanted from the Indian subcontinent to work as indentured laborers in the sugar fields of the Natal colony.

Many of these laborers were already familiar with, and used, cannabis back in their native India — also a British colony at the time. Their continued use of cannabis became a point of worry for the colonial authorities, as they feared that the Indian workers were not as physically productive when on the drug.

Many colonists also began to fear that the drug was causing the subjugated non-white population to go insane, increasing incidents of crime and acting as an incubator for interracial relationships. Racist theories claiming that these “inferior races” were more likely to commit crime based on their biological traits began to proliferate from some of the most prominent European scientists of the time. As such, they believed that cannabis usage amongst the non-whites was stimulating their supposed inherent predisposition to commit crime.

Despite this moral panic surrounding cannabis, it appears that the colonial masters at the time were primarily concerned not with the well-being of their Indian subjects, but with the fear that cannabis was “sapping the vitality of the Indian worker” and thus negatively impacting their profits. As such, in 1870, all Indians living within the Natal colony were prohibited from cultivating, possessing and selling any quantity of cannabis when Natal passed the “Coolie Consolidation Law of 1870.” [Note: the term “coolie” is an offensive and derogatory term that was used to refer to Indian indentured workers throughout the former British Empire.]

Cannabis was still allowed to be sold to other groups, but the trade was coming under increased scrutiny as part of the drug scare of the early 20th century — this included fears over the abuse of other popular drugs like heroin and cocaine. Cannabis would ultimately be banned totally in South Africa in 1928 and would remain so for nearly a century, well after the 1994 transition to democracy.

Despite this, cannabis continued to be sold and distributed in mass quantities during the entirety of the prohibition era. Those involved in the underground trade included people from various different cultural, religious and economic backgrounds. From the white farmer looking to retain the services of his workers, to the left-wing revolutionaries fighting the apartheid government and looking to fund the movement with quick cash, the shadow economy continued.

During the Apartheid era, the government enacted harsh punishments against anyone caught dealing or possessing cannabis. However, large scale cannabis cultivation within the, semi-autonomous, racially segregated Bantustans in the dagga belt continued relatively untouched, as authorities appeared to give an implicit approval for the crop’s cultivation — so long as it stayed within the Bantustans. This tacit approval appeared to last until the height of the U.S.-led war on drugs in the late 1980s, which saw South African police spraying large amounts of herbicides over rural cannabis farms in the dagga belt.

Much of the cannabis would ultimately make it out to the wider South African and even international markets. In this way, South Africa’s racially segregationist and prohibitionist policies were actually producing the opposite of their intended effect.

Large amounts of South African cannabis began to hit the European markets in the 1960s, as the international hippie movement was in full swing. In this way, South African cannabis was further propelled into the international trade, as some of the predominantly white South African hippies with European connections would become importers of South African cannabis into the western world. There are theories that argue that some of these South African strains would be cross-bred with European strains to bring about some of the world’s most popular and iconic cannabis strains known today.

After the fall of Apartheid in 1994, some were optimistic that the South African cannabis trade could be formally legalized or, at the very least, decriminalized by their new rulers in the African National Congress. There are reports indicating that during the anti-Apartheid struggle, the ANC had raised a substantial amount of money from the South African cannabis trade. On the other hand, the party was also known to maintain strict anti-cannabis policies within the numerous exile camps they controlled in other African countries outside of South Africa.

Nevertheless, in the post-Apartheid era, the ANC would extend South Africa’s cannabis prohibitionist policies by incarcerating large numbers of people for cannabis possession and distribution. They would also continue to send police helicopters to spray poisonous herbicides, particularly over the over dagga belt areas in the Eastern Cape.

As mentioned earlier, during the drug wars of the late 1980s the Apartheid government began using a highly toxic chemical known as paraquat to kill off large swaths of cannabis, along with any other subsistence crop that was exposed to it.

Chris Albertyn, an environmental activist, who participated in a coalition of various environmental groups trying to get the government to stop the paraquat sprayings at the time, spoke with Unicorn Riot.

“The thing about paraquat is that it kills everything it comes in contact with — not just the cannabis but everything from your [maize] to the chickens etc., whoever and whatever it comes into contact with is affected by this toxic chemical that’s been banned in numerous countries but not South Africa.”

Chris Albertyn

The environmentalist group’s efforts were ultimately successful as the government declared in 1990 that it would no longer use paraquat in its aerial eradication programs — stopping short of eliminating these programs all together. Though the South African Police Service no longer uses it for aerial eradication, paraquat is still available and widely used in everyday South African agriculture.

Years later, the successor government would switch to using yet another highly controversial and toxic chemical, glyphosate — more popularly known by its brand name “Roundup,” patented by the agricultural giant Monsanto now part of Bayer — is the most commonly used herbicide in the world.

At the time, the South African Police Service claimed that its particular version of glyphosate was “no threat to human, animal, or environmental health.” Glyphosate has since been identified by the World Health Organization as “a probable carcinogen to humans.”

Yet again, environmental organizations came together in an effort to ban the use of this herbicide by filing a legal challenge. That challenge was ultimately successful and there have been no further reports of police spraying herbicides in the Eastern Cape since.

Still, many local amaMpondo people are seeking reparations for losses sustained from the chemical, including “losing their lives to unnatural causes, […] significant damage to waterways, livestock, food crops, human health, culture, and heritage.”

Legislative and Judicial Cannabis Reform

In 2014, Mario Oriani-Ambrosini, an MP for the Inkatha Freedom Party, formally introduced legislation to legalize medical cannabis. The Italian-born, Harvard-educated doctor and politician had a very personal reason for pushing the reform bill; 15 months prior he had been diagnosed with lung cancer.

In his speech to Parliament, Oriani-Ambrosini openly admitted to breaking the law and using cannabis illegally to treat his condition. He would go on to credit his cannabis usage as the very reason he was even able to speak at Parliament that day:

“I was supposed to die many months ago and I am here because I had the courage of taking illegal treatments in Italy in the form of bicarbonate of soda and here in South Africa in the form of cannabis, marijuana or dagga.”

Dr. Mario Oriani-Ambrosini

The bill also proposed legalizing the cultivation of the non-psychoactive cannabis product hemp for commercial and industrial purposes. Hemp is used around the world as a fabric, construction material, food, and more.

After revealing his illness and cannabis treatment, Oriani-Ambrosini would only live on for another 15 months before passing away from his condition at the age of 53. His introduction of the Medical Innovation Bill, however, would help destigmatize cannabis use, leading to drastic changes.

As a result, the Department of Health amended its policies in 2017 allowing for the legal cultivation and trade of medical cannabis. This would be followed separately by the Constitutional Court’s 2018 ruling decriminalizing cannabis use and possession within a person’s private space.

That ruling was the result of an entirely separate legal challenge tracing back to 1998 when Rastafarian law student Gareth Prince was denied a license to practice law due to his previous criminal record of cannabis possession. He, along with a cannabis advocacy group known as the “Dagga Party” originally filed their legal challenge in 2002 arguing that Prince had a religious right to possess the drug. After a drawn-out 16 year legal battle Prince and the Dagga Party would emerge victorious.

Current Status

While progress in cannabis reform has been made, many are complaining that these reforms don’t go far enough. That’s mostly because the distribution and trading of cannabis for recreational purposes is still illegal. And while medical cannabis is legal to sell, it can only be obtained legally by those with doctor’s prescriptions.

Those that wish to enter the business of cultivating and selling medical cannabis are subject to a very intensive, complicated and expensive application process — one that could last years before they’re allowed to open shop.

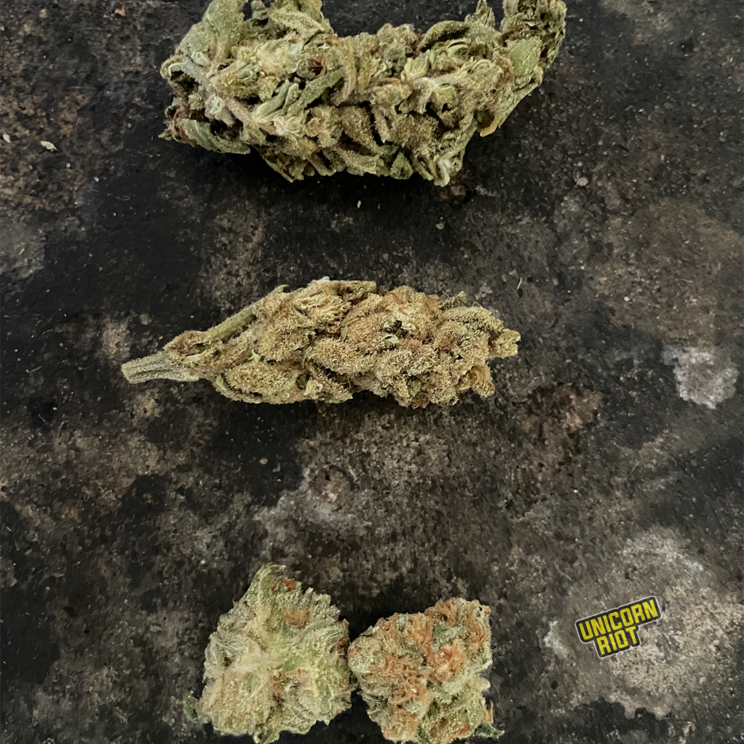

Despite the continued ban on recreational sales, many of these clubs and dispensaries are currently selling large amounts of recreational cannabis — typically anywhere between $3-6 or R60-R120 in local currency per gram to whoever is able to pay.

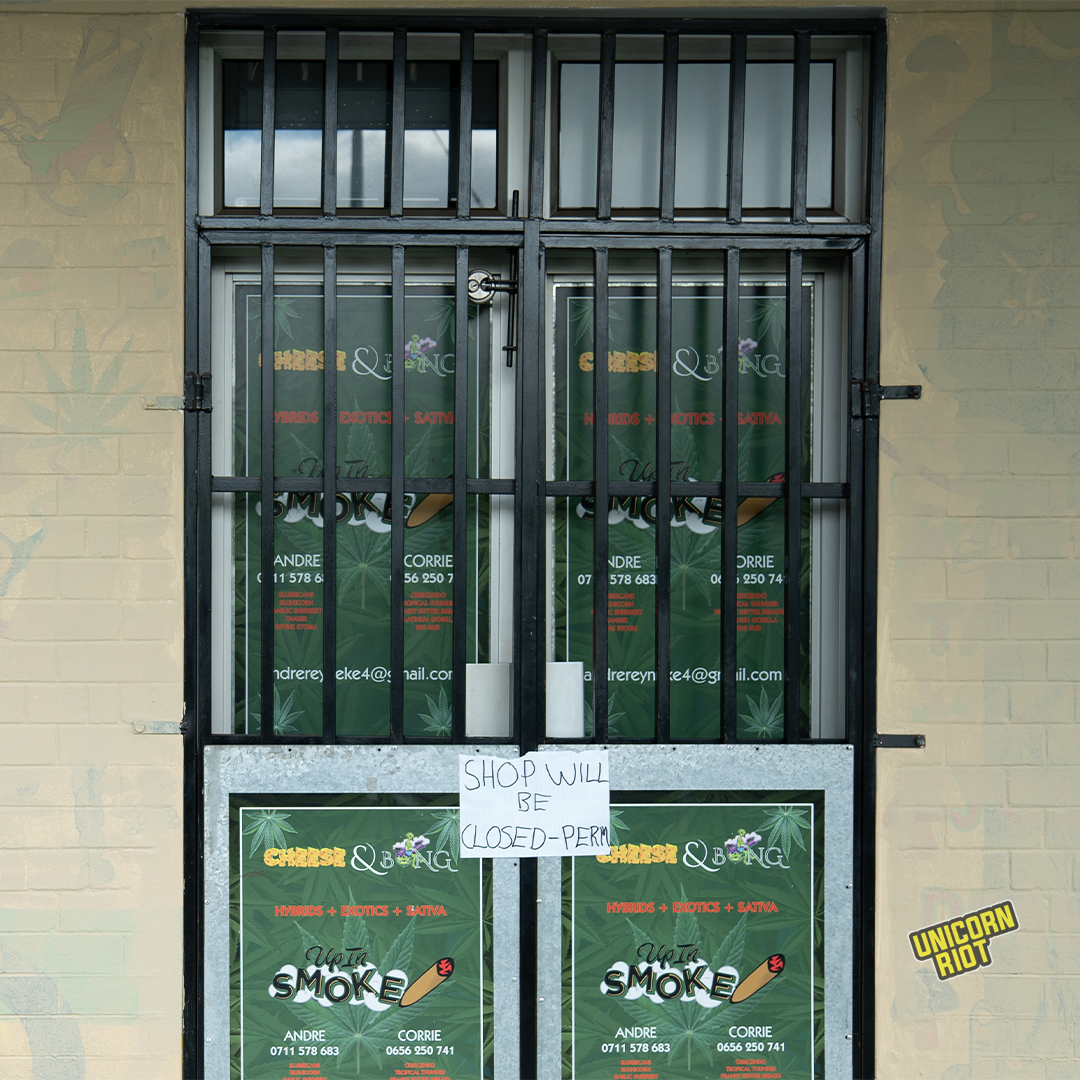

For the most part, the police have appeared to turn a blind eye to this blatant illegal activity, perhaps due to the fact that they are overwhelmed with much bigger problems. This has led to a state of general confusion regarding the legality of cannabis. Regardless, the South African Police Service has publicly stated that if it receives reports about any business illegally dealing cannabis it will move to shut down their operations.

In reality, most dispensaries are openly selling cannabis products to whoever is willing to buy. In fact, some dispensaries have said that the local police have even supported and protected them from prosecution.

However, not all of these new businesses have had the benefit of having such cordial relationships with authorities. Unicorn Riot briefly spoke with the owner of one such business located in Durban’s Glenwood neighborhood by the name Cheese & Bong. The owner stated that the business had only been operational for a year before being forced to close down after the South African Health Products Regulatory Authority denied him a license to sell medical cannabis.

Smaller businesses are finding it very difficult to survive in a market that almost guarantees strong profit margins, but requires considerable startup cash and time. Even if one is successful, smaller business owners must then compete with the larger businesses that dominate the market.

To make matters more complex, some business owners have reported coming into contact with a variety of criminal groups seeking to extract “protection fees” or extortion payments from them. Those that refuse risk having their shipments intercepted by armed robbers, or worse. Anonymous sources told Unicorn Riot that several cannabis businesses operating in Kwazulu-Natal have had their shipments robbed by criminal groups originating from Johannesburg.

A Bright New Green Future, or Drug Wars 2.0?

Cannabis reform and the subsequent boom in the industry has undoubtedly opened up significant business opportunities in South Africa and has stimulated economic growth in an otherwise stagnant and decaying economy. It has also had huge affects on healthcare, assisting countless people suffering from a variety of illnesses.

However, many major unresolved issues and questions remain concerning cannabis legalization and its economic impacts — particularly on independent rural farmers and small businesses.

The exceptionally high bar for entry to get a license to cultivate and sell cannabis products is a significant barrier that prevents many of the poorest and most disadvantaged people from entering the legal market. Severe income inequality persists in South Africa meaning that non-whites, particularly blacks, have significantly less resources than their white counterparts. This includes a noticeable difference between the typical incomes of black and white farmers.

In the post-cannabis legalization era there have been several high-profile protests organized by the Black Farmers Association of South Africa against the South African Health Products Regulatory Authority for maintaining “the white monopoly colonialists in our cannabis industry with no thought of improving and allowing the less fortunate and previously disadvantaged into the industry.”

The South African Health Products Regulatory Authority has denied the charges that it favors more affluent white farmers over black farmers, while acknowledging that the licensing process is a rigorous one, but that it has to be in order to “ensure that potential healthcare products are safe and effective for human use.”

Still, there is a noticeable discrepancy between black and white ownership, as it’s generally more common to see white cannabis business owners as opposed to black ones. This is a consistent pattern observed across virtually all major industries in South Africa.

Some have also highlighted that in terms of quality, the traditional outdoor cannabis growers of the dagga belt are not able to compete with the high-grade cannabis grown in specialized indoor facilities that the legal dispensaries are offering. This may explain why rural farmers have seen their profits drop since legalization. But whatever their product may lack in quality, it generally makes up for in quantity, which could be especially useful in terms of hemp production.

But even if one does have the money and time to acquire a license to produce and sell cannabis, selling it for recreational use is still a criminal offense. Few of the new cannabis businesses appear to be aware of this fact, or are otherwise paying it no attention.

The complicated and confusing nature of the new cannabis laws has also created a type of wild west environment where cannabis distributors stand to make huge profits, but risk being shut down or extorted by corrupt authorities selectively enforcing the law and/or by criminal syndicates operating completely outside of the law.

In terms of criminal justice, as of 2022, around 3,000 people were incarcerated within South Africa’s massively overcrowded prison system for cannabis related offenses. Back in 2019, then-minister of Correctional Services Ronald Lamola stated these prisoners would “have to apply to President Cyril Ramaphosa for pardons.” indicating that the majority of them have probably not been freed — if any at all.

Problems aside, what can’t be disputed is that the historic wins achieved by the pro-cannabis movement since 2018 have opened the possibility towards full legalization — something which was almost unthinkable just a decade ago.

Cover image: 2023 Global Cannabis March in Cape Town, South Africa/Fields of Green for ALL

Follow us on X (aka Twitter), Facebook, YouTube, Vimeo, Instagram, Mastodon, Threads, BlueSky and Patreon.

Please consider a tax-deductible donation to help sustain our horizontally-organized, non-profit media organization:

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post