Study on the evolution of ecological environment and irrigation behavior since mulched dri

April 28, 2025

Abstract

Analyzing the ecological and behavioral effects of changes in irrigation practices in oases provides valuable insights for water resource management and the sustainable development of oasis agriculture in arid regions. Taking the Yanqi Basin as a case study, this research draws on long-term empirical data and remote sensing information to evaluate the ecological and irrigation behavior effects resulting from shifts in irrigation methods. And explores the deep societal causes behind these behavioral changes. The findings demonstrate: (1). Between 2000 and 2010, the rapid adoption of groundwater extraction and mulched drip irrigation (MDI) technology temporarily alleviated the water supply-demand contradiction. However, from 2010 to 2020, as the adoption of water-saving practices significantly expanded and agricultural irrigation areas grew substantially, the irrigation paradox emerged, where increased efficiency paradoxically led to greater water consumption. (2). From 2000 to 2020, the groundwater table depth in the irrigation district dropped by 8–16 m, total soluble salt content decreased by 2–5 g/L, and soil salinity decreased by 4–12 g/kg. The proportion of severely salinized and saline soil areas fell from 21.74% in 1999 to 9.75% in 2020. The longstanding salinization issues that had plagued the irrigation district were effectively mitigated with the widespread adoption of MDI. (3). The irrigation district’s vegetation ecological quality index (VEQI) showed a slow but steady upward trend in cultivated areas over the years. In contrast, natural vegetation areas such as forests and grasslands exhibited an initial increase followed by a decline. The trends in VEQI responded well to changes in irrigation practices. (4). The economic benefits driven by water-saving technologies and the expansion of cultivated land are deep societal factors behind the changes in irrigation behavior. These benefits also fostered improvements in users’ understanding and awareness of irrigation practices. The shift in irrigation methods in the Yanqi Basin has led to a decline in groundwater levels, an irrigation paradox, and moderate damage to natural vegetation. However, it has had a significant positive impact on improving regional groundwater quality and mitigating soil salinization. Furthermore, it facilitates the further exploration of regional water conservation potential, enhancing the research on the regional water and soil resource management system.

Introduction

Irrigation water is a critical limiting factor for ensuring the productivity and sustainability of modern agriculture. The global shortage of water resources poses a significant threat to the sustainable development of irrigated agriculture1. This issue is particularly acute in arid regions, where the conflict between water supply and demand is especially pronounced, and the interaction between social systems and hydrological systems is exceptionally tight2. Enhancing irrigation water efficiency from multiple dimensions is one of the core strategies for achieving the sustainable development of modern agriculture. To address the challenges of irrigation water in arid regions and alleviate the pressure of agricultural water usage, extensive research, and practical efforts have been undertaken. In the 1950s, with the gradual improvement of canal seepage prevention standards, composite seepage prevention methods combining plastic membranes or foam boards with rigid protective surfaces became mainstream3. In the 1980s, the concept of MDI technology was introduced based on plastic film mulching techniques, representing another breakthrough in traditional surface irrigation methods. This technique quickly became the primary form of water-saving irrigation promoted in the Xinjiang region4. Between 1996 and 1998, a series of MDI experiments in the Shihezi reclamation area of the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps were successfully conducted, marking the beginning of the widespread adoption of water-saving irrigation technologies in Xinjiang3. In 1998, the Yanqi Basin began promoting water-saving irrigation technologies, aiming to improve agricultural water use efficiency by advancing irrigation methods and curbing the rapid growth of agricultural water consumption. This effort ushered in a new phase of development for water-saving agriculture in the region.

Long-term agricultural practices have demonstrated that MDI offers significant advantages in several aspects, including the efficient utilization of water resources5,6, suppression of secondary soil salinization5,7,8, reduction of deep percolation losses6,9,10, and addressing challenges related to late-stage fertilization11). By delivering frequent, low-volume irrigation, drip irrigation systems maintain consistently high soil moisture levels in the crop root zone, creating a favorable environment of water, nutrients, aeration, and temperature for crop growth12. This effectively alleviates issues of delayed water supply under drought stress13,14. Additionally, the use of plastic film mulch suppresses soil evaporation and prevents the surface accumulation of salts beneath the film. As a result, aside from a slight accumulation of salinity in the exposed bare soil between the film rows due to evaporation, the majority of salts are concentrated near the wetting front15,16. Studies on the distribution of salt under MDI systems have found that a desalination zone forms within the soil-wetting front, providing an optimal water-salt environment for the crop root zone. Furthermore, soil salinity in the cultivated layer has shown a gradual downward trend over the years17. In arid and semi-arid regions characterized by low rainfall, high evaporation, and high soil salinity, MDI technology integrates the respective advantages of drip irrigation and plastic film mulching. This innovation not only reduces evaporation and percolation losses while improving water use efficiency but also effectively inhibits the accumulation of salts on the soil surface18‌. In arid regions, related research indicates that MDI systems reduce water usage by 50-70% and fertilizer usage by 47.5% for vegetable production compared to furrow irrigation while increasing cotton yields by 18-44%19, Furthermore, it helps control greenhouse gas emissions and reduces risks such as pest and disease outbreaks20. MDI is highly versatile and applicable to a wide range of crops, including vegetables, fruits, maize, potatoes, and rice, as well as cash crops like cotton and soybeans. This makes it a promising solution for the development of efficient water-saving irrigation systems in inland arid regions. Xinjiang is the primary region in China where MDI has been developed, tested, and widely implemented. The initial research and promotion of MDI in China began in Xinjiang, achieving remarkable results. Today, the technology is well-established and continues to mature. Since the promotion of MDI in Xinjiang began in 1998, the initial adoption rate was relatively slow, with MDI covering only 12.2% of the total irrigated area by 2008. However, by 2011, the coverage had reached 30.1%, entering a phase of rapid growth21. By the end of 2018, MDI coverage had increased to 56.7% of the total irrigated area and continues to rise. As a representative region with pronounced water resource supply-demand conflicts, the Yanqi Basin has demonstrated a slightly higher adoption rate of drip irrigation technology compared to the Xinjiang average.

On the other hand, while promoting MDI technology, it is crucial to address potential issues such as soil salinization in irrigation districts, groundwater degradation, and ecological damage to natural vegetation. In arid regions, irrigation serves not only agricultural production but also plays a vital role in sustaining oasis ecosystems, providing dual benefits of agricultural productivity and ecological services. Relevant studies have shown that in traditional agricultural irrigation, the unconsumed portion of water often returns to surface water bodies via runoff and drainage or recharges underground aquifers22. Additionally, natural vegetation ecosystems account for 39.8% of the total evapotranspiration of irrigation water, highlighting the significant ecological support provided by irrigation water23. In China’s Hetao Irrigation District in Inner Mongolia, large-scale implementation of efficient MDI began in 1998. Since then, the annual net water diversion has decreased from 5.2 × 10� m³ to 4.7 × 10� m³, leading to significant changes in the district’s water cycle and groundwater table depth24. However, as MDI progressed, the areas of fallow lands—critical for “dry drainage� of salts during the cropping season—gradually diminished, resulting in the redistribution of soil salinity in arid regions25. Similarly, in the Tarim River Basin, the large-scale promotion of MDI has significantly expanded irrigated areas. This expansion has led to unstable oasis scales, where agricultural water use has increasingly encroached on ecological water supplies, contributing to regional land degradation, desertification, and damage to natural vegetation ecosystems26. Other studies have found that after implementing MDI, agricultural water consumption increased27. The intended water-saving benefits of these technologies are often offset by additional water demand driven by increased agricultural production, resulting in a paradox where water use does not decrease and may even increase28,29.

In arid regions, traditional flood irrigation methods not only meet crop water requirements but also play a crucial role in leaching salts from the soil. While there has been substantial research on the water-saving effects of transitioning irrigation methods in arid areas, systematic reviews on whether agricultural water use rebounds after the implementation of MDI and whether natural vegetation and ecosystems are adversely affected remain scarce. Furthermore, due to differences in research scales in water-saving studies30, the current singular focus on reducing irrigation quotas and improving irrigation water use efficiency, while alleviating water supply-demand conflicts, may also have unintended consequences on regional soil-water environments and downstream ecosystems31,32.Indicators such as the normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI)33,34, net primary productivity (NPP) of vegetation35,36, fractional vegetation cover (FVC)37, ecological index (EI)38, and remote sensing ecological index (RSEI)39,40 are widely used to assess vegetation and ecosystem conditions. Among these, NPP and FVC are two critical metrics that directly reflect the growth vigor and productive capacity of natural vegetation communities41,42. Based on NPP and FVC, the vegetation ecological quality index (VEQI) can be constructed, which comprehensively reflects vegetation productivity per unit area and its spatial coverage capacity. This approach addresses challenges in evaluating vegetation ecological quality when NPP is identical but FVC differs, or vice versa, and enables quantitative comparisons of vegetation ecological quality across time and space43. This study focuses on the Yanqi Basin irrigation district as the target area. Using extensive measured data from 1999, 2005, 2014, and 2020 on groundwater levels, water quality, and soil salinization, combined with land-use/land-cover (LUCC) data and remote sensing imagery, the study applies GIS technology to analyze the trends in soil salinization, groundwater conditions, VEQI, and irrigation water use efficiency within the irrigation district. The aim is to elucidate the ecological and irrigation behavior effects in the Yanqi Basin since the implementation of MDI. The findings will provide valuable insights for advancing irrigation reforms in arid regions, achieving efficient agricultural water resource utilization, and protecting ecological environments within irrigation districts.

Data and methods

Overview of the study area

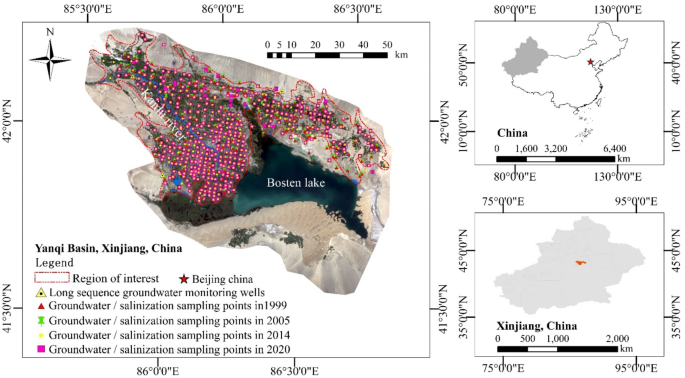

The Yanqi Basin is located in Bayingolin Mongol Autonomous Prefecture (hereafter referred to as Bayingolin), Xinjiang, China. Geographically, it lies between 85°15′–87°15′E and 41°15′–42°30′N, forming a semi-enclosed intermontane basin in the northeastern part of the Tarim Basin. The region includes the counties of Yanqi, Hejing, Heshuo, and Bohu, as well as eight farms under the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps, including Farms 21–27 and Farm 223. Characterized by low precipitation and high evaporation, the Yanqi Basin is a typical arid desert basin oasis in China, with distinctive arid region oasis climatic features44. The overall topography of the study area is characterized by a northwest-high, southeast-low gradient, with mountains surrounding the basin and Bosten Lake situated at its center. The water system follows the terrain, with water converging from the surrounding areas toward the central lake. Groundwater in the region is primarily recharged through two main processes: infiltration from the mountain fronts and conversion from surface water. It is mainly stored in the alluvial fans, and the alluvial, floodplain, and lacustrine deposits of the plains. The aquifers consist of Quaternary deposits, ranging from the Upper Pleistocene to Holocene alluvial and floodplain layers, and form a horizontal belt that extends from the mountain front to the central basin around Bosten Lake. Groundwater depth exhibits distinct characteristics across different regions: it exceeds 50 m in the mountain-front flood fans, ranges from 20 to 30 m in the central region of the alluvial fans, from 3 to 10 m in the alluvial plains, and is less than 3 m in the lakeside areas. The alluvial fan regions at the basin margins consist of gravel and sand-gravel deserts with sparse vegetation, primarily desert plants such as Ephedra, Calligonum, and Nitraria. In the plains, soil distribution follows a gradient from the mountain front to Bosten Lake, including brown desert soil, irrigated brown desert soil, irrigated or alluvial soils, fluvo-aquic soil, irrigated meadow soil, meadow saline soil, typical saline soil, and saline marsh soil. The main crops include tomatoes, peppers, corn, wheat, sugar beets, and cotton, reflecting diverse cropping systems. Irrigation methods have largely shifted to MDI for all crops except for wheat and orchards, which still rely on traditional flood irrigation. To mitigate soil salinization, different areas employ tailored winter irrigation frequencies and quotas based on soil salinity levels. This study focuses on the contiguous irrigated areas within the basin, encompassing a total area of 3,568 km² with an average elevation of 1,200 m (Fig. 1).

Data sources

Other information on groundwater, soil salinity and irrigation water consumption in the irrigation area

Groundwater data for the irrigation district includes groundwater depth and the total dissolved solid (TDS) within the study area. These data were collected by the research team over multiple years through direct measurements from irrigation wells during non-irrigation periods in the Yanqi Basin. Specifically, shallow groundwater depth and TDS data were collected in April of 1999, 2005, 2014, and 2020 (before the spring irrigation season), with a total of 189, 90, 145, and 92 datasets recorded for each respective year. Additionally, long-term groundwater monitoring data were obtained from three permanent monitoring wells located in the plain areas of the Yanqi Basin. Soil salinity data were collected using soil augers to obtain soil samples from the surface to a depth of 10 cm in cultivated fields. Sampling was conducted prior to spring irrigation, with sample times and locations corresponding closely to groundwater measurement sites. The study includes 176, 178, 142, and 148 soil samples from 1999, 2005, 2014, and 2020, respectively (Table 1). Additional data for the irrigation district include regional irrigation water usage, irrigated area, water-saving area, and the irrigation water utilization coefficient. These data were sourced from the Statistical Compilation of Water Resources in Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region.

Remote sensing data

The remote sensing data includes LUCC, NPP, and NDVI, LUCC was obtained from the Resource and Environment Science and Data Center of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (http://www.resdc.cn) and encompass six time points: 1980, 1990, 2000, 2005, 2010, and 2020. NPP was derived from the MODIS17A3 dataset, accessed via Google Earth Engine (GEE), for five specific years: 2000, 2005, 2010, 2014, and 2020. NDVI were interpreted from Landsat series remote sensing imagery, provided by the United States Geological Survey (https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/). The imagery was selected for the corresponding NPP years, focusing on the July–September period, with low cloud coverage and optimal vegetation growth conditions (details are provided in Table 2). The remote sensing data were preprocessed and analyzed using statistical software such as ENVI and ArcGIS Pro.

Research methodology

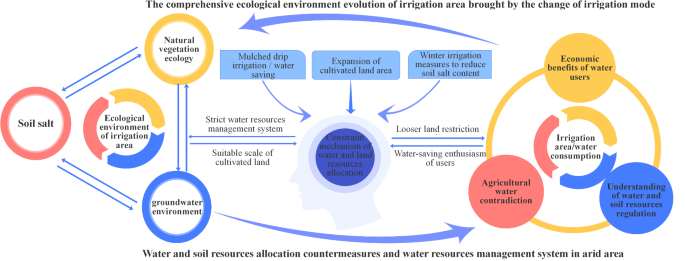

This study focuses on the Yanqi Basin as the target area, aiming to analyze the evolution trends of soil salinization, groundwater environment, and the ecological quality of natural vegetation within the basin’s irrigated areas. By investigating the feedback mechanisms among the groundwater environment, vegetation ecology, and soil salinization, the study seeks to evaluate the ecological and irrigation effects in the basin since the implementation of large-scale water-saving practices. The findings provide a scientific basis for formulating practical water and soil resource allocation strategies for the basin. The research framework is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Land use transfer matrix

The land use transition matrix is used to describe the area and quantity of land use changes among different categories during the study period, representing a further application of the Markov chain45. By constructing a Sankey diagram based on the transition matrix, the proportions of various land use types can be visually represented. Additionally, the thickness of the flow lines in the Sankey diagram vividly reflects the inflow and outflow relationships between different land use types, as well as the intensity of their transitions. The formula is as follows:

(S_ij=left[ beginarray*20c S_11&S_12& cdots &S_1n \ S_21&S_22& cdots &S_2n \ cdots & cdots & cdots & cdots \ S_n1&S_n2& cdots &S_nn endarray right])

Where Sij is the proportion of land area, n is 6, and i and j are the land use type numbers at the beginning and end of the study, respectively.

Construction of a comprehensive ecological quality index for vegetation cover

NPP and FVC are two of the most direct indicators of vegetation ecological quality. However, using either NPP or FVC alone only reflects one aspect of vegetation’s ecological quality, such as its productivity or coverage capacity. Without considering vegetation diversity, a comprehensive model can be constructed by integrating NPP and FVC using a weighted method to develop the VEQI46. The calculation model for the annual VEQI is as follows:

(VEQI_i=100 times left( f_1 times FVC_i+f_2 times fracNPP_iNPP_hboxmax right))

In the formula, VEQIi represents the VEQI for year i, which ranges from 0 to 100. The coefficient f1 is the weight assigned to the annual average FVC, and f2 is the weight for the annual NPP of vegetation. FVCi is the average FVC for year i, NPPi is the vegetation NPP for the same year, and NPPmax is the historical maximum value of vegetation NPP.

Linear trend method

Using the linear trend method combined with GIS technology, the change linear trend rate (K) of the VEQI can be implemented on a per-pixel basis. This approach allows for the quantitative description of the spatiotemporal characteristics and the extent of changes at the raster scale. The calculation formula is as follows:

(K=fracn times sumnolimits_i=1^n (i times x_i) – sumnolimits_i^n i times sumnolimits_i^n x_i n times sumnolimits_i=1^n i^2 – left( sumnolimits_i=1^n i right)^2)

In the formula, K represents the linear trend rate; n is the length of the annual series, with n = 5; i represents the specific year in the time series; Xi is the variable value for year i. The magnitude of K indicates the tendency of the variable to rise or fall: if K > 0, it signifies an upward trend as year i increases; if K < 0, it indicates a downward trend with increasing years.

Results and analysis

Shift in irrigation practices

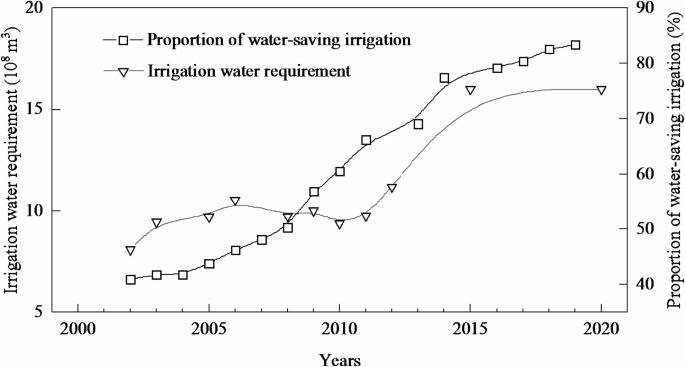

The MDI method offers advantages such as water conservation and ease of management, enabling precise control over irrigation to better ensure the normal growth of crops. In the 1990s, as the irrigated area in the Yanqi Basin expanded on a large scale and conflicts over agricultural water use intensified, the traditional surface irrigation method was gradually replaced by MDI. From the trends in agricultural water consumption and water-saving coverage in the Yanqi Basin (Fig. 3), it is evident that the adoption of MDI in the region experienced a significant upward trend from 2000 to 2020, with the water-saving coverage rate reaching 83.35% by 2020. Regarding its growth rate, the trend can be divided into three phases: slow, fast, and slow. A turning point occurred around 2010, when the adoption rate of MDI reached its peak growth rate. Conversely, agricultural water consumption exhibited a fluctuating upward trend. From 2000 to 2010, water consumption remained relatively stable; from 2010 to 2015, it increased significantly; and from 2015 to 2020, it showed a notable downward trend.

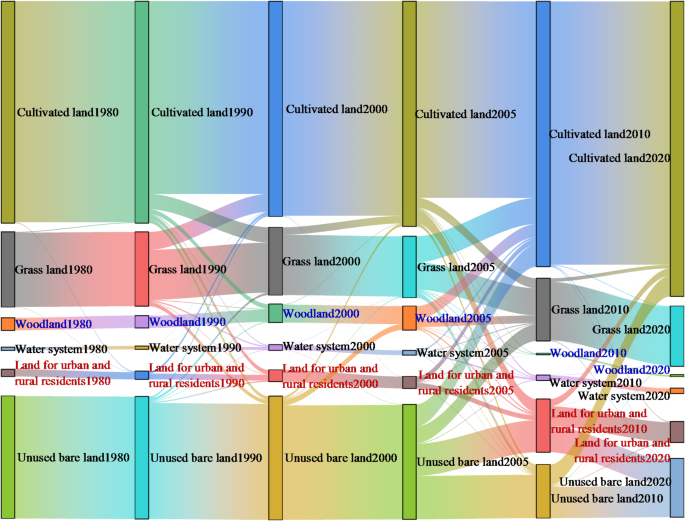

Based on the land use transition Sankey diagram for the Yanqi Basin (Fig. 4), it can be observed that from 1980 to 1990, there was almost no change in the area of various land use types. Between 1990 and 2000, only minor mutual conversions occurred between cultivated land and grassland, while from 2000 to 2005, a small amount of grassland was converted into cultivated land. This indicates that during the period from 1980 to 2005, prior to and at the early stages of the irrigation method transition, the overall land use pattern remained relatively stable. However, significant changes occurred between 2005 and 2010, with large amounts of unused land and grassland being converted into cultivated land, and some unused land being transformed into urban and rural residential land. From 2010 to 2020, with the large-scale adoption of MDI practices, further conversion of unused land into cultivated land took place, leading to a new peak in irrigated areas and water usage.

In summary, the transformation of irrigation methods in the Yanqi Basin can be categorized into two phases: The Early Stage of Water Conservation (2000 ~ 2010): During this period, agricultural water consumption remained relatively stable. Water-saving technologies began to be adopted, and irrigation areas and water consumption were in a balance characterized by low water-use efficiency. The Large-Scale Adoption of MDI (2010 ~ 2020): With the widespread implementation of MDI, agricultural water consumption paradoxically increased rather than decreased, leading to the phenomenon of “the more water-saving, the greater the water shortage.� The shift in irrigation practices in the Yanqi Basin can be attributed to several factors. Water-saving technologies reduced irrigation quotas and suppressed the crop water demand during the growing season, temporarily alleviating the conflict between water supply and demand. At the same time, the dual incentives of low investment and high returns from water-saving technologies, combined with the expansion of irrigated areas, led to a rapid increase in cultivated land. This created an unstable pattern of “the more water-saving, the more land is reclaimed; the more land is reclaimed, the greater the need for water-saving.� This feedback loop significantly increased farmers’ enthusiasm for adopting MDI. As a result, irrigation practices shifted from being government-driven in the early stages to user-driven in the later stages.

However, when the additional water demand from the expanded irrigation area surpassed the water saved through water conservation efforts, the potential for further water savings was exhausted, forcing a halt to the expansion of irrigated areas. This indicates that while the rapid development of MDI significantly reduced irrigation quotas, it also triggered complex ripple effects. Rather than mitigating water supply-demand conflicts, these developments risked ushering in a new wave of competition for water resources. From a long-term perspective, the advancement of water-saving technologies only temporarily alleviated the conflict over agricultural water use. To sustainably address the relationship between humans and water, irrigation management must shift towards a coordinated development approach that equally emphasizes the promotion of water-saving technologies and the control of cultivated land expansion.

Evolution of the regional groundwater environment

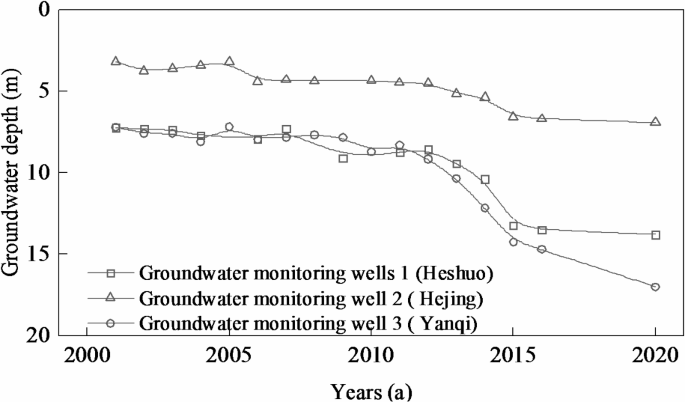

The groundwater level dynamics of three long-term monitoring wells in the Yanqi Basin (Fig. 5) reveal a highly consistent trend across all wells, with the overall groundwater level exhibiting a significant decline. In terms of the rate of change during different periods, groundwater levels remained relatively stable from 2000 to 2005, showed a gradual decline between 2005 and 2010, experienced a sharp drop from 2010 to 2015, and then slowed to a gradual decline from 2015 to 2020. The differences in groundwater depth trends across these periods can be attributed to the following factors: After the large-scale implementation of water-saving measures in 2000, agricultural water use conflicts were temporarily alleviated in the short term. However, after 2005, with the continued promotion of water-saving technologies and the rapid expansion of irrigation areas, regions within the basin that could not be supplied by surface water began to rely on groundwater-fed irrigation zones, where wells were combined with MDI. This led to a continuous annual decline in groundwater levels. Between 2010 and 2015, the expansion of irrigation areas reached a historical peak (Fig. 4), resulting in a sharp drop in groundwater levels during this period. After 2015, with the emergence of the “irrigation paradox� and increasing awareness of irrigation practices, water authorities attempted to curb the continued growth of irrigation water use through policies such as total water use limits. However, the economic benefits driven by water-saving technology dividends and the expansion of irrigation areas hindered the effective implementation of water resource management policies. Consequently, groundwater levels continued to decline in later years, with trends in groundwater level changes remaining closely aligned with the expansion of irrigated areas.

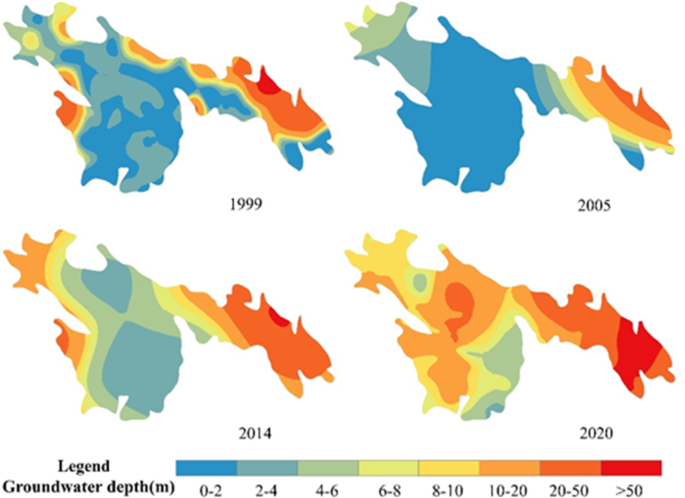

According to the spatial distribution maps of groundwater depth across different periods in the irrigation district of the Yanqi Basin (Fig. 6), the groundwater depth exhibits a characteristic pattern: deeper in the northern foothill areas and shallower in the southern region surrounding Bosten Lake. Over the years, the groundwater level has experienced a significant decline, with a general decrease ranging from 8 to 16 m across the irrigation district, and localized declines in the eastern region exceeding 20 m. In terms of temporal changes, from 1999 to 2005, groundwater depth showed a slow rising trend, with an overall increase of 0 to 2 m. From 2005 to 2014, the groundwater level exhibited a significant decline, particularly in the western region, where localized maximum declines exceeded 10 m. After 2014, significant declines also began to appear in the central and eastern parts of the irrigation district. By 2020, groundwater depths across most of the basin ranged from 10 to 20 m, while in the northeastern region, depths were predominantly between 20 and 50 m, with some localized areas exceeding 50 m. These trends and the magnitude of changes are consistent with the observations from the three long-term groundwater monitoring wells.

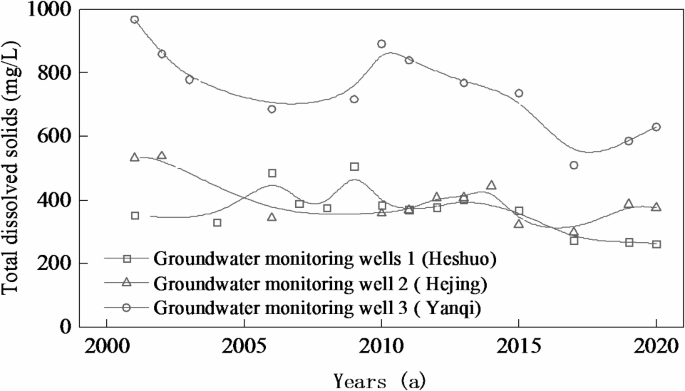

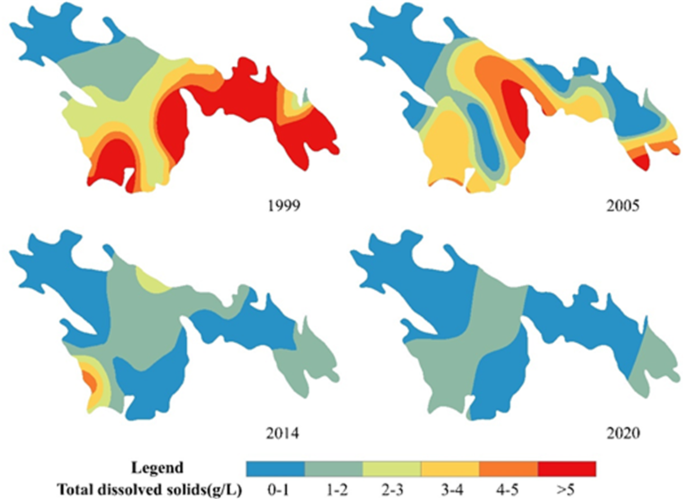

The dynamic changes in groundwater TDS observed from the three long-term monitoring wells in the Yanqi Basin (Fig. 7) show that the TDS levels in the northern region, as well as in Hejing and Heshuo County, are significantly lower than those in the southern part of Yanqi County. Overall, the trends in the data from the three monitoring wells are consistent, with TDS showing a slow, gradual decline. In terms of the degree of change, the northern region experiences relatively stable fluctuations, while the southern region shows more significant variations. The overall TDS of groundwater in the irrigation area follows a pattern of higher TDS in the south and lower TDS in the north (Fig. 8), and has shown a significant downward trend over the years. Both the spatial distribution and the trend of change align with the results from the three monitoring wells. From 1999 to 2005, the high- TDS areas in the southern region around Bosten Lake experienced a notable decrease, dropping from over 5 g/L to 3–5 g/L. Between 2005 and 2014, the groundwater TDS across the entire irrigation district showed a marked decline, particularly in the central region, where TDS decreased from 3 to 5 g/L to 1–2 g/L. After 2014, the few remaining high- TDS areas also began to decline significantly, and by 2020, groundwater TDS across the irrigation district was predominantly in the range of 0–2 g/L.

The differing trends between groundwater depth and TDS tion of MDI technology temporarily reduced agricultural water consumption, resulting in a short-term recovery of groundwater levels in the basin. From 2005 to 2010, with the rapid expansion of irrigated areas and the increased use of MDI, the same amount of irrigation water was distributed over a larger area. This not only reduced irrigation quotas but also increased regional evaporation, diminishing the recharge of groundwater from irrigation water and causing groundwater levels to decline. After 2010, as the available surface water for irrigation became insufficient to meet the demands of continuously expanding farmland, newly reclaimed agricultural areas relied heavily on groundwater extraction for irrigation. This led to the formation of groundwater-fed irrigation zones or mixed irrigation zones in the eastern and central parts of the irrigation district. The increased pumping of groundwater in these areas caused a sharp drop in groundwater levels, further intensifying the “irrigation paradox.� The declining groundwater levels increased the hydraulic gradient between rivers and the aquifer, accelerating the rate of river recharge into the groundwater. This surface water recharge, combined with its dilution effect on groundwater, led to a sustained decrease in groundwater TDS across the region over the years.

Spatial and Temporal evolution of soil salinization in irrigation areas

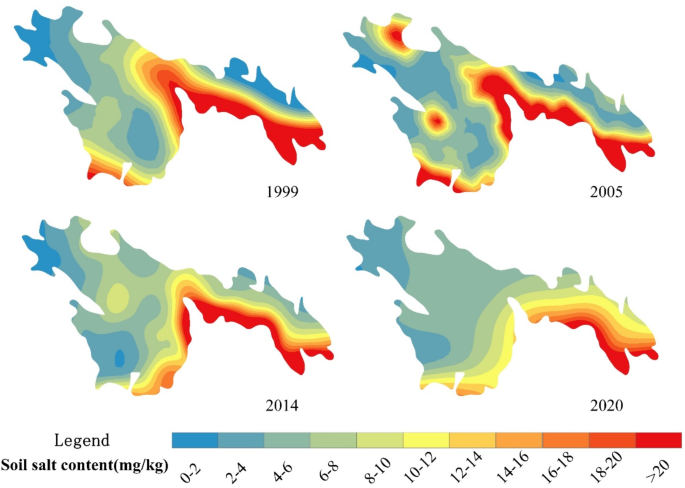

The distribution maps of surface soil salinity across different periods (Fig. 9) indicate that soil salinity in the irrigation district exhibits a spatial pattern of higher salinity around the Bosten Lake region. From 1999 to 2005, salinization showed an overall increasing trend. In 1999, areas with soil salinity greater than 20 g/kg were primarily concentrated around the lake. By 2005, localized patches with salinity greater than 20 g/kg emerged and were scattered throughout the irrigation district. With the further adoption of MDI technology, salinization showed a significant declining trend by 2014. This reduction was particularly notable in the areas surrounding the lake and other high-salinity regions, where patches previously exceeding 20 g/kg decreased to 6–10 g/kg. From 2014 to 2020, the high-salinity areas around the lake continued to shrink, while soil salinity in the central part of the irrigation district declined by 2–4 g/kg. By 2020, except for localized areas near the lake, soil salinity across the irrigation district was predominantly within the range of 0–10 g/kg.

The areas and changing trends of various salinization categories (Table 3) indicate that non-salinized soils dominate the irrigation district, with their area steadily increasing over time. Between 1999 and 2005, significant changes were observed in the areas of severely salinized soils and saline soils, with a noticeable transition from severe salinization to saline soils. From 2005 to 2014, the areas of moderately and severely salinized soils, as well as saline soils, experienced varying degrees of decline, with a particularly notable reduction in saline soil areas. During this period, the areas of non-salinized and slightly salinized soils exhibited an increasing trend. After 2014, the small remaining areas of saline soils and severely salinized soils continued to decrease, while moderately salinized soils showed an increase. The changes in the areas of non-salinized and slightly salinized soils were less pronounced. By 2020, the proportion of severely salinized soils and saline soils in the irrigation district had decreased from 21.74% in 1999 to 9.75%. Over the years, with the widespread adoption of MDI practices, severely salinized soils and saline soils have progressively transitioned into non-salinized, slightly salinized, and moderately salinized soils. The shift in irrigation methods has played a significant role in reducing the degree of soil salinization in the region.

Evaluation of integrated ecological quality of irrigation areas

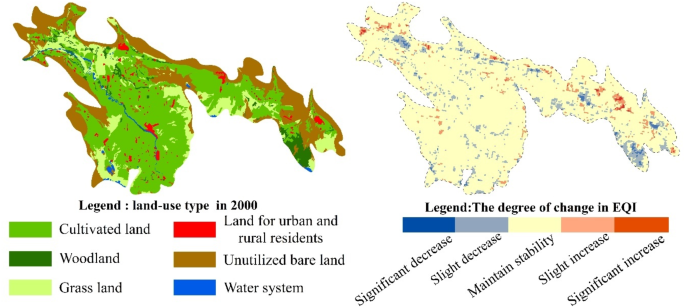

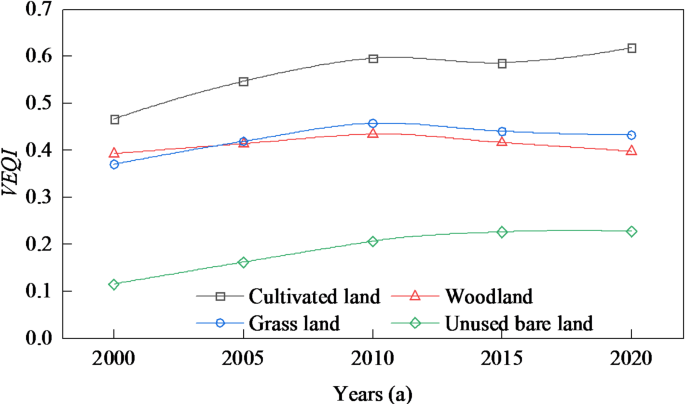

Between 2000 and 2020, the spatial variation in the change of the VEQI within the irrigation district exhibited significant differences (Fig. 10). Over the years, the overall VEQI of the irrigation district remained relatively stable, with only a small area experiencing significant changes, which were scattered and fragmented in distribution. Areas with increasing VEQI were mainly located in certain unused lands in the northern part of the district, while areas with decreasing VEQI were sporadically distributed throughout the irrigation district. These declining areas were primarily found in southeastern forestlands, localized grasslands in the northwest, and areas along river systems. In terms of VEQI changes across different land use types (Fig. 11), cropland and unused bare land showed a consistent but slight upward trend in VEQI. However, for natural vegetation types such as forestland and grassland, VEQI initially increased, reaching its peak in 2010, followed by a gradual decline thereafter.

The differing spatial trends in VEQI can be attributed to several factors: During the initial stages of water-saving efforts, the transition in irrigation practices reduced agricultural water consumption to some extent, ensuring adequate ecological water use. This allowed for the improvement of both farmland’s ecological quality and the ecological quality of natural vegetation. However, after 2010, as water-saving technologies advanced further, the increased overall irrigation water usage—combined with reduced irrigation quotas and the expansion of irrigated areas—limited the return flow of irrigation water to the natural ecosystem. This led to a decline in VEQI for natural vegetation within the irrigation district. The trends in VEQI responded well to the changes in irrigation methods. In the initial stages of implementing water-saving measures, the rate of water savings achieved through enhanced irrigation methods exceeded the additional water demand induced by the expansion of cropland. This resulted in a positive balance in the competition for water resources between modern agriculture and the ecological environment, leading to a gradual yet consistent increase in the VEQI. However, in the later stages of water-saving implementation, when the additional water demand from cropland expansion exceeded the rate of water savings—indicating that the potential for further water savings had been exhausted, competition for water between agriculture and the ecological environment became negative. This inevitably caused slight ecological degradation of natural vegetation, such as forestlands and grasslands on the periphery of the irrigation district.

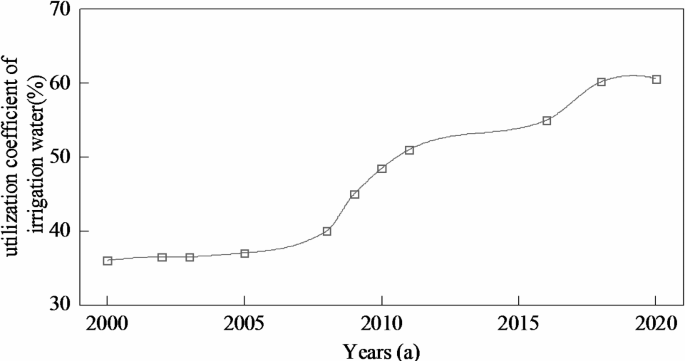

Increased user perception of irrigation

With the adoption of MDI technology and the gradual improvement in users’ awareness of new irrigation methods, irrigation practices have shifted from the early-stage practice of fully saturating the soil surface to the current approach of irrigating just until water is visible along the edges of the membrane. This shift has led to a continuous reduction in irrigation quotas and significantly improved irrigation water use efficiency. The trend of irrigation water use efficiency in the Yanqi Basin (Fig. 12) demonstrates that between 2000 and 2020, the efficiency increased from 36.0% before the implementation of water-saving measures to 60.6% by 2020. This growth unfolded in three phases: slow growth, rapid growth, and another phase of slow growth, with a turning point around 2010, when the growth rate peaked.

The changes in irrigation water use efficiency corresponded well to the expansion of irrigated areas and the transition in irrigation practices. Users’ attitudes toward irrigation have also improved significantly, evolving from initial skepticism and hesitation to eventual trust and even reliance. Early drip irrigation projects, initially promoted through government-led demonstrations, have now evolved into voluntary initiatives driven by the users themselves. Drip irrigation has achieved near-complete coverage across all crops, including wheat, with a water-saving adoption rate exceeding 90%. This indicates that the water-saving potential of irrigation infrastructure has essentially reached its upper limit.

The key factors driving the improvement in users’ awareness of irrigation and their increasing enthusiasm for water-saving practices lie in the transformation brought about by new irrigation technologies. Under traditional irrigation methods, limited by inefficient practices and high costs, land cultivation could only be maintained at a corresponding scale. In contrast, MDI has significantly improved on-farm water use efficiency, revolutionized farming practices and intensity, reduced labor demands substantially, and effectively increased crop yields. The economic benefits resulting from the expansion of irrigated land have become a critical driving force for agricultural development in irrigation districts, aligning with traditional values and rational economic demands. At this point, the new irrigation methods have matured, and the external conditions required to capitalize on land resources have been fully established, making the expansion of cultivated land an inevitable outcome.

The dual economic benefits of cost reduction and efficiency enhancement brought by water-saving technologies, combined with the economic returns from irrigation district expansion, have further enhanced users’ understanding of irrigation practices. This has also increased their tolerance for rising water fees, effectively reducing resistance to the implementation of water resource management policies. As a result, conflicts between users and water management authorities have been alleviated, creating favorable conditions for further tapping into regional water-saving potential and advancing the development of water and land resource management systems.

Discussion

Feedback mechanisms of water and salt evolution on irrigation shift in arid zones

After the shift in irrigation practices in the Yanqi Basin, irrigation water uses initially decreased and then increased, reflecting the “pendulum process� in the competition for water resources between modern agriculture and the ecological environment. This transition also shifted the primary issue in the irrigation district from salinization under inefficient water use to groundwater overexploitation and ecological problems under efficient water use. These findings align with the results of studies on agricultural water use evolution in arid and semi-arid regions, such as Lu et al. (2018)47 on the Heihe River Basin in China, Kandasamy et al. (2014)48on the Murrumbidgee River Basin in Australia, and Han et al. (2017)49the North China Plain. Traditional flood irrigation methods, while meeting crop water requirements, also played a significant role in leaching soil salts and regulating soil’s physical and chemical properties50,51. After the adoption of water-saving technologies, the Yanqi Basin introduced winter irrigation as a means of salt leaching. Surveys show that the typical winter irrigation quota in the basin is around 200 m³/acre, or even higher—exceeding 50% of the total crop water demand during the growing season. As a result, water-saving measures primarily reduced irrigation quotas during the crop growth period, providing only temporary relief to supply-demand conflicts during peak water-use periods. However, on an annual basis, irrigation quotas did not decrease significantly, which is one of the main reasons for the emergence of the “irrigation paradox.�

Looking at the entire process of water-saving implementation, during the early stages, the adoption of water-saving technologies was limited (Fig. 3), and the expansion of cultivated land was not significant (Fig. 4). This situation prevented the salts accumulated in the upper soil layers from being leached downward promptly, while new salts continued to accumulate at the surface. This disrupted the established salinization patterns under traditional flood irrigation practices, exacerbating secondary salinization in the topsoil (Fig. 9). This is the fundamental reason why both groundwater levels and soil salinization showed an upward trend during the early stages of water-saving efforts. In the later stages of water-saving implementation, however, the continuous expansion of irrigated areas and the increase in irrigation water use led to the relentless extraction of surface water for agricultural irrigation, the encroachment on ecological water resources, and the overexploitation of groundwater52. This caused excessive groundwater use and a decline in groundwater levels (Fig. 5), as well as mild degradation of natural vegetation ecosystems (Fig. 9). At the same time, the continuous drop in groundwater levels disrupted the hydraulic gradient between groundwater and surface water bodies, such as rivers. Under the influence of the unique groundwater flow system in the Yanqi Basin53, this led to an increase in the recharge and exchange rates of surface water to groundwater. Consequently, groundwater quality in the region improved significantly due to the diluting effect of surface water (Fig. 8). As the groundwater environment evolved, the intensity of phreatic evaporation decreased, reducing the upward movement of salts carried by groundwater to the soil surface. This effectively mitigated the risk of secondary soil salinization. Additionally, the implementation of winter irrigation for salt leaching further reduced the salt content in the cultivated soil layer. As a result, during the later stages of water-saving efforts, soil salinity in the plow layer showed a significant decline (Fig. 9).

In the early stages of the transition in irrigation practices in the Yanqi Basin, the adoption of water-saving measures led to a reduction in irrigation water use, with groundwater levels remaining relatively stable. However, new secondary salinization appeared in the upper soil layers. In the later stages, the “irrigation paradox� emerged, characterized by a general decline in soil surface salinity and an improvement in groundwater TDS. These findings align with the results of Zhang et al. (2014)54on the Tarim River Basin, Sun et al. (2022)24 on the Hetao Irrigation District, He et al. (2019)55on the Weigan River Basin, Zhang et al. (2015)56 on the Yellow River Delta, and Shi et al. (2023)57on 10 major arid river basins worldwide, including the Nile River and the Tigris-Euphrates River, and other similar regions, all of which explored the evolution of salinization trends following long-term implementation of MDI. This evidence suggests that, as irrigation practices evolve and the adoption of water-saving measures increases, significant expansion of cultivated land and the emergence of the “irrigation paradox� are stimulated. At the same time, improvements in regional groundwater quality and reductions in soil salinization are achieved. These conclusions demonstrate the broad applicability of such outcomes in arid regions.

Water resource management strategies for agriculture in arid regions

In arid regions, the combination of groundwater utilization and MDI technology during the crop growing season represents a significant improvement over the traditional surface flood irrigation method used previously. During the non-growing season, traditional winter and spring irrigation practices play a crucial role in promoting soil desalination within irrigation districts58,59. The adoption of MDI has led to a gradual annual reduction in soil salinization, effectively addressing the long-standing challenge of soil salinization that has plagued irrigation districts in arid regions.

At present, MDI has become the dominant production model in irrigation districts of arid regions. This technology has, to some extent, influenced and transformed people’s perceptions and understanding, bringing significant economic benefits to farmers and improving local economic conditions, thus garnering widespread support. However, within an irrigation system, the decrease in irrigation quotas combined with the substantial expansion of irrigated areas has led to a significant increase in regional evapotranspiration. This has reduced the proportion of agricultural irrigation water returning to the ecosystem and recharging groundwater49, causing mild damage to the natural ecological environment of the region and further intensifying the trend of desertification14. Consequently, the coordinated development of modern agriculture and the ecological environment in arid regions faces heightened challenges. This situation aligns with the “irrigation efficiency paradox� proposed by Professor R. Q. Grafton of the Crawford School of Public Policy at the Australian National University60. The benefits brought by new technologies have created a widespread reliance on them, forming a path dependency, but at the same time, new ecological and environmental problems have emerged. The expansion of cultivated land stimulated by the promotion of water-saving technologies is also a key factor contributing to the occurrence of the irrigation paradox in arid regions22,29,61.

In the management of water resources in arid regions, avoiding the negative effects of high-efficiency water-saving technologies requires the government and relevant management authorities to propose appropriate countermeasures to regulate the allocation relationship between water and soil resources62. On the basis of advancing water-saving technologies, it is crucial to emphasize coordination with water resource management policies and ecological environment protection63. In addition to preventing new issues such as the irrigation paradox that may arise from overly relaxed farmland restrictions, it is equally important to avoid overly stringent farmland restriction policies that could discourage the adoption of water-saving technologies and lead to rebound effects22. Given the current strict water resource management system, land size control mechanisms, and the simultaneous need to ensure food security for key agricultural products and stable farmer incomes, finding an optimal balance between water and land resources has become an urgent issue for irrigation districts64. To address these challenges, water resource management authorities have proposed several strategies based on the actual conditions of irrigation districts, including:â‘ For irrigation districts experiencing groundwater overexploitation, appropriately reducing the cultivated area in the short term. â‘¡ For irrigation districts exceeding their allocated water usage, focusing on unlocking the potential for water-saving measures, such as adjusting cropping patterns, reducing irrigation quotas, and limiting winter and spring irrigation areas. While these strategies appear to be highly targeted, their practical implementation may not yield entirely satisfactory results. Effective execution still requires negotiation and collaboration between management authorities and water users, with the overarching goal of achieving environmental sustainability.

The transition in irrigation methods also signifies that the adoption of new technologies within irrigation systems has disrupted previously stable irrigation practices. MDI, while improving user convenience and efficiency, has significantly altered the relationship between humans and the environment. Under traditional, relatively low-productivity irrigation models, a relatively stable relationship between humans and the environment often developed within irrigation districts. However, with the introduction of new technologies, this balance has gradually been disrupted, leading to the formation of new modes of coexistence. As these technologies continue to evolve, the extent and capacity of human activities to alter the environment have also significantly increased65. Irrigation districts have shifted from traditional policy-driven approaches focused on drought resistance, well-drilling, irrigation infrastructure improvements, and establishing high-yield3, reliable cropping zones to an industrialized management model emphasizing large-scale land expansion, total water usage control, and groundwater level monitoring66. While new irrigation technologies have addressed inefficiencies in water use, they have also introduced new challenges, such as the irrigation paradox. The emergence and impact of these issues are as rapid and significant as the advantages these technologies bring. From the recent transition in irrigation practices in the Yanqi Basin, general patterns can be observed regarding the ecological and behavioral effects of irrigation changes. Irrigation practices, as indicators of productivity levels in irrigation districts, can alter the human-environment relationship within these districts to a certain extent. However, once this relationship becomes entrenched, external forces are often required to break the resulting issues. When the existing balance is disrupted, new problems inevitably arise, creating cycles of “crisis� and “transformation.� The challenges faced by irrigation districts in the Yanqi Basin are highly representative of broader issues encountered in arid regions.

Conclusion

The transition of irrigation methods in the Yanqi Basin can be divided into two stages. In the initial stage, the water-saving effects were significant, resulting in a reduction of irrigation water usage, which can be characterized as the “water-saving popularization—agricultural water-saving� phase. In the mid-to-late stage of water conservation, with the expansion of irrigated areas, the phenomenon of the irrigation paradox emerged, marking the “scaled water-saving—irrigation paradox� phase. The expansion of irrigated areas following the shift in irrigation methods led to a significant decline in regional groundwater levels, which in turn triggered the irrigation paradox. On the other hand, the change in irrigation practices ensured a positive development of the agricultural ecological environment and had a notable positive impact on improving the groundwater quality and mitigating soil salinization in the irrigation area.

The new technological dividends brought about by the shift in irrigation methods are a key driving force behind the agricultural development in the irrigation area, and represent a deeper societal cause of the irrigation paradox. This transition has also shifted the primary issue in the irrigation area from soil salinization under inefficient water use to groundwater over-extraction and ecological environmental problems under efficient water use. Currently, the change in irrigation practices has also promoted continuous improvement in the awareness of both water management departments and users regarding water-saving irrigation. This has become a societal focus, driving both parties to move closer toward environmentally friendly practices in the ongoing water management and usage debate. It is expected to help resolve the issues of groundwater over-extraction and ecological degradation in the irrigation area.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

-

Falkenmark, M. Growing water scarcity in agriculture: future challenge to global water security. Philos. Trans. R Soc. Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 371, 20120410. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2012.0410 (2013).

-

Wesselink, A., Kooy, M. & Warner, J. Socio-hydrology and hydrosocial analysis: toward dialogues across disciplines. WIREs Water. 4, e1196. https://doi.org/10.1002/wat2.1196 (2017).

-

Zhong, R. S., Dong, X. G. & Ma, Y. J. Sustainable water saving: new concept of modern agricultural water saving, starting from development of Xinjiang’s agricultural irrigation over the last 50 years. Irrig. Drain. 58, 383–392. https://doi.org/10.1002/ird.414 (2009).

-

Ma, Y. J., He, J. W., Hong, M. & Zhao, J. H. Development process and trend analysis of Xinjiang Sub-membrane drip irrigation technology. Water Sav. Irrig. 12, 87–89. https://doi.org/10.CNKI:SUN:JSGU.0.2010-12-027 (2010). (2010).

-

Li, S. X., Wang, Z. H., Li, S. Q., Gao, Y. J. & Tian, X. H. Effect of plastic sheet mulch, wheat straw mulch, and maize growth on water loss by evaporation in dryland areas of China. Agric. Water Manag. 116, 39–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2012.10.004 (2013).

-

Qin, W., Hu, C. S. & Oenema, O. Soil mulching significantly enhances yields and water and nitrogen use efficiencies of maize and wheat: a meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 5, 16210. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep16210 (2015).

-

Kang, Y. H., Chen, M. & Wan, S. Q. Effects of drip irrigation with saline water on waxy maize (Zea mays L. Var. ceratina Kulesh) in North China plain. Agric. Water Manag. 97, 1303–1309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2010.03.006 (2010).

-

Wang, L. et al. Reclamation of saline soil by planting annual euhalophyte Suaeda Salsa with drip irrigation: A three-year field experiment in arid Northwestern China. Ecol. Eng. 159, 106090. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoleng.2020.106090 (2021).

-

Zhao, L. W. & Zhao, W. Z. Water balance and migration for maize in an Oasis farmland of Northwest China. Chin. Sci. Bull. 59, 4829–4837. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11434-014-0482-4 (2014).

-

Xu, X., Huang, G. H., Qu, Z. Y. & Pereira, L. S. Assessing the groundwater dynamics and impacts of water saving in the Hetao irrigation district, yellow river basin. Agric. Water Manag. 98, 301–313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2010.08.025 (2010).

-

Yan, S. C. et al. Effects of water and fertilizer management on grain filling characteristics, grain weight and productivity of drip-fertigated winter wheat. Agric. Water Manag. 213, 983–995. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2018.12.019 (2019).

-

Fan, J. C., Lu, X. J., Gu, S. H. & Guo, X. Y. Improving nutrient and water use efficiencies using water-drip irrigation and fertilization technology in Northeast China. Agric. Water Manag. 241, 106352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2020.106352 (2020).

-

Sui, J. et al. Assessment of maize yield-increasing potential and optimum N level under mulched drip irrigation in the Northeast of China. Field Crops Res. 215, 132–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr.2017.10.009 (2018).

-

Wu, D. et al. Effect of different drip fertigation methods on maize yield, nutrient and water productivity in two-soils in Northeast China. Agric. Water Manag. 213, 200–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2019.05.021 (2019).

-

Liu, M. X. et al. Distribution and dynamics of soil water and salt under different drip irrigation regimes in Northwest China. Irrig. Sci. 31, 675–688. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00271-012-0343-3 (2013).

-

Jia, Q. Q., Chen, W. W., Tong, Y. M. & Guo, Q. L. Experimental study on capillary migration of water and salt in wall painting plastera case study at Mogao grottoes, China. Int. J. Archit. Herit. 16, 705–716. https://doi.org/10.1080/15583058.2020.1839598 (2022).

-

Wang, Q. J., Wang, W. Y., Lu, D. Q., Wang, Z. R. & Zhang, J. F. Water and Salt Transport Features for Salt-Effected Soil Through Drip Irrigation Under Film. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agricultural Eng. 4(16) 54–57. https://doi.org/10.3321/j.issn:1002-6819.2000.04.014(2000). (2000).

-

Zhou, H. P., Zhao, J. H., Zhang, N., Zhai, C. & Liu, Y. F. Infiltration of irrigation water and energy saving test of maize. Sci. Sin Technol. 49, 76–86. https://doi.org/10.1360/N092018-00028 (2019).

-

Li, Y., Wang, W. Y. & Wang, Q. J. A Breakthrough Thought for Water Saving and Salinity Control in Arid and Semi-arid Area— Under-film trickle irrigation. Irrigation and Drainage. 02(20) 42–46. (2001). https://doi.org/10.13522/j.cnki.ggps.2001.02.012 (2001).

-

Zhuang, Y. H. et al. Effects and potential of water-saving irrigation for rice production in China. Agric. Water Manag. 217, 374–382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2019.03.010 (2019).

-

Zhou, H. P., Zhang, M. Y., Zhou, Q., Sun, Z. F. & Chen, J. L. Analysis of agricultural irrigation water-using coefficient in Xinjiang arid region. Transactions of the Chinese Society of Agricultural Engineering. 22(29), 100–107. (2013). https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1002-6819.2013.22.012 (2013).

-

Dumont, A., Mayor, B. & López-Gunn, E. Is the rebound effect or Jevons paradox a useful concept for better management of water resources?? Insights from the irrigation modernisation process in Spain. Aquat. Procedia. 1, 64–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aqpro.2013.07.006 (2013).

-

Zhang, Y. C. et al. Effects of drip irrigation technical parameters on cotton growth, soil moisture and salinity in Southern Xinjiang. Transactions of the Chinese Society of Agricultural Engineering. 24(36), 107–117. (2020). https://doi.org/10.11975/j.issn.1002-6819.2020.24.013 (2020).

-

Sun, Y. N. et al. Evolution Mechanism of Soil Salinization in Hetao Irrigation District under Condition of Water-saving Reform Based on Remote Sensing Technology. Transactions of the Chinese Society for Agricultural Machinery. 12(53), 366–379. (2022). https://doi.org/10.6041/j.issn.1000-1298.2022.12.036 (2022).

-

Li, B., Shi, H. B., Tuo, D. B., Li, Z. & Zhang, G. J. Soil Salinity Profile Characteristics and Its Spatial Distribution before and after Water Saving —Taking the Middle Reach in Hetao Irrigation District of Inner Mongolia as an Example. Arid Zone Research.32(4), 644–673. (2015). https://doi.org/10.13866/j.azr.2015.04.05 (2015).

-

Chen, Y. N. & Chen, Z. S. Analysis of oasis evolution and suitable development scale for arid regions: a case study of the Tarim River Basin. Chinese Journal of Ecological Agriculture 21(1), 134–140. (2013). https://doi.org/10.3724/SP.J.1011.2013.00134 (2013).

-

Perry, C. Accounting for water use: terminology and implications for saving water and increasing production. Agric. Water Manag. 98, 1840–1846. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2010.10.002 (2011).

-

Zhou, X. Y. et al. Did water-saving irrigation protect water resources over the past 40 years? A global analysis based on water accounting framework. Agric. Water Manag. 249, 106793. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2021.106793 (2021).

-

Scott, C. A., Vicuña, S., Blanco-Gutiérrez, I., Meza, F. & Varela-Ortega, C. Irrigation efficiency and water-policy implications for river basin resilience. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 18, 1339–1348. https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-18-1339-2014 (2014).

-

Clemmens, A. J., Allen, R. G. & Burt, C. M. Technical concepts related to conservation of irrigation and rainwater in agricultural systems. Water Resour. Res. 44, 2007WR006095. https://doi.org/10.1029/2007WR006095 (2008).

-

Chen, H. R. et al. Scale effects of water saving on irrigation efficiency: case study of a Rice-Based groundwater irrigation system on the Sanjiang plain, Northeast China. Sustainability 10, 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10010047 (2017).

-

Jiang, G. Y. & Wang, Z. J. Scale effects of ecological safety of Water-Saving irrigation: A case study in the arid inland river basin of Northwest China. Water 11, 1886. https://doi.org/10.3390/w11091886 (2019).

-

Erasmi, S., Klinge, M., Dulamsuren, C., Schneider, F. & Hauck, M. Modelling the productivity of Siberian larch forests from Landsat NDVI time series in fragmented forest stands of the Mongolian forest-steppe. Environ. Monit. Assess. 193, 200. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-021-08996-1 (2021).

-

Jiang, L. G., Liu, Y., Wu, S. & Yang, C. Analyzing ecological environment change and associated driving factors in China based on NDVI time series data. Ecol. Indic. 129, 107933. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2021.107933 (2021).

-

Jiang, L. L., Guli, J., Bao, A. M., Guo, H. & Ndayisaba, F. Vegetation dynamics and responses to climate change and human activities in central Asia. Sci. Total Environ. 599–600, 967–980. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.05.012 (2017).

-

Zhang, X. L. et al. Spatial-temporal changes in NPP and its relationship with climate factors based on sensitivity analysis in the Shiyang river basin. J. Earth Syst. Sci. 129, 24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12040-019-1267-6 (2020).

-

Liu, H. Y., Zhang, M. Y., Lin, Z. S. & Xu, X. J. Spatial heterogeneity of the relationship between vegetation dynamics and climate change and their driving forces at multiple time scales in Southwest China. Agric. Meteorol. 256–257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet.2018.02.015 (2018).

-

Hawkins, C. P., Cao, Y. & Roper, B. Method of predicting reference condition biota affects the performance and interpretation of ecological indices. Freshw. Biol. 55, 1066–1085. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2427.2009.02357.x (2010).

-

Zheng, Z. H., Wu, Z. F., Chen, Y. B., Yang, Z. W. & Marinello, F. Exploration of eco-environment and urbanization changes in coastal zones: A case study in China over the past 20 years. Ecol. Indic. 119, 106847. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2020.106847 (2020).

-

Xu, D. et al. Quantization of the coupling mechanism between eco-environmental quality and urbanization from multisource remote sensing data. J. Clean. Prod. 321, 128948. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.128948 (2021).

-

Xu, C. et al. Evaluating the difference between the normalized difference vegetation index and net primary productivity as the indicators of vegetation Vigor assessment at landscape scale. Environ. Monit. Assess. 184, 1275–1286. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-011-2039-1 (2012).

-

Li, C. et al. Spatiotemporal pattern of vegetation ecology quality and its response to climate change between 2000–2017 in China. Sustainability 13, 1419. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031419 (2021).

-

Yang, X., Huang, H. H., Qian, S. & Yan, H. Research on vegetation Ecologic quality index of Rocky desertification in karst area of Guangxi Province based on NPP and fractional vegetation cover since 2000. Comput. Comput. Technol. Agric. XI. 225–230. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-06179-1_23 (2019).

-

Mamat, Z., Yimit, H., Ji, R. Z. A. & Eziz, M. Source identification and hazardous risk delineation of heavy metal contamination in Yanqi basin, Northwest China. Sci. Total Environ. 493, 1098–1111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.03.087 (2014).

-

Goigel Turner, M. A Spatial simulation model of land use changes in a Piedmont County in Georgia. Appl. Math. Comput. 27, 39–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/0096-3003(88)90097-5 (1988).

-

Qian, S. et al. Dynamic monitoring and evaluation model for spatio-temporal change of comprehensive ecological quality of vegetation. Acta Ecol. Sin. 40, 6573–6583. https://doi.org/10.5846/stxb201906041188 (2020).

-

Lu, Z. X. et al. Co-evolutionary dynamics of the human-environment system in the Heihe river basin in the past 2000 years. Sci. Total Environ. 635, 412–422. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.03.231 (2018).

-

Kandasamy, J. et al. Socio-hydrologic drivers of the pendulum swing between agricultural development and environmental health: a case study from murrumbidgee river basin, Australia. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 18, 1027–1041. https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-18-1027-2014 (2014).

-

Han, S. J., Xu, D. & Yang, Z. Y. Irrigation-Induced changes in evapotranspiration demand of Awati irrigation district, Northwest China: weakening the effects of. Water Saving? Sustain. 9, 1531. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9091531 (2017).

-

Wang, X. Y. et al. Soil properties and agricultural practices shape microbial communities in flooded and rainfed croplands. Appl. Soil. Ecol. 147, 103449. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsoil.2019.103449 (2020).

-

Xie, L. N. et al. Effects of waterlogging and increased salinity on microbial communities and extracellular enzyme activity in native and exotic marsh vegetation soils. Soil. Sci. Soc. Am. J. 84, 82–98. https://doi.org/10.1002/saj2.20006 (2020).

-

Liu, C. M., Yu, J. J. & Eloise, K. Groundwater exploitation and its impact on the environment in the North China plain. Water Int. 26, 265–272. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508060108686913 (2001).

-

Wu, M. et al. Evaluating the interactions between surface water and groundwater in the arid mid-eastern Yanqi basin, Northwestern China. Hydrol. Sci. J. 63, 1313–1331. https://doi.org/10.1080/02626667.2018.1500744 (2018).

-

Zhang, Z., Hu, H., Tian, F., Yao, X. & Sivapalan, M. Groundwater dynamics under water-saving irrigation and implications for sustainable water management in an Oasis: Tarim river basin of Western China. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 18, 3951–3967. https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-18-3951-2014 (2014).

-

He, B. Z., Ding, J. L., Liu, B. H. & Wang, J. Z. Spatiotemporal variation of soil salinization in Weigan�Kuqa river Delta Oasis. Scientia Silvae Sinicae. 09 (55), 185–196. https://doi.org/10.11707/j.1001-7488.20190920 (2019).

-

Zhang, T. T. et al. Detecting soil salinity with MODIS time series VI data. Ecol. Indic. 52, 480–489. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2015.01.004 (2015).

-

Shi, H. Y. et al. Recent impacts of water management on Dryland’s salinization and degradation neutralization. Sci. Bull. 68, 3240–3251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scib.2023.11.012 (2023).

-

Liu, Z. P. et al. Effects of winter irrigation on soil salinity and jujube growth in arid regions. PLOS ONE. 14, e0218622. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0218622 (2019).

-

Yang, P. N., Zia-Khan, S., Wei, G. H., Zhong, R. S. & Aguila, M. Winter irrigation effects in cotton fields in arid inland irrigated areas in the North of the Tarim basin, China. Water 8, 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/w8020047 (2016).

-

Grafton, R. Q. et al. The paradox of irrigation efficiency. Science 361, 748–750. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aat9314 (2018).

-

Zhang, L. N. et al. Empirical Analysis and Countermeasures of the Irrigation Efficiency Paradox in the Shenwu Irrigation Area, China. Water 12, 3142. (2020). https://doi.org/10.3390/w12113142

-

Gleick, P. H., WATER IN CRISIS: PATHS TO SUSTAINABLE WATER USE & Ecol Appl 8, 571–579. https://doi.org/10.1890/1051-0761 (1998). (1998)008[0571:WICPTS]2.0.CO;2.

-

Zhao, D. D. et al. Quantifying economic-social-environmental trade-offs and synergies of water-supply constraints: an application to the capital region of China. Water Res. 195, 116986. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2021.116986 (2021).

-

Li, M. et al. Efficient allocation of agricultural land and water resources for soil environment protection using a mixed optimization-simulation approach under uncertainty. Geoderma 353, 55–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2019.06.023 (2019).

-

Oldfield, F. & Dearing, J. A. The Role of Human Activities in Past Environmental Change. in Paleoclimate, Global Change and the Future (eds. Alverson, K. D., Pedersen, T. F. & Bradley, R. S.) 143–162. (2003). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-55828-3_7

-

Liu, Y., Tian, F., Hu, H. & Sivapalan, M. Socio-hydrologic perspectives of the co-evolution of humans and water in the Tarim river basin, Western China: the Taiji–Tire model. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 18, 1289–1303. https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-18-1289-2014 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the large-scale water-saving and irrigation water-salt response study in the Weigan River Basin (2023.D-002).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Wang Yongpeng wrote the full text, drawing tables and pictures ; yang Pengnian provided the overall idea, reviewed the article, and provided financial support ; the data of groundwater and soil salt content in 1999,2005 and 2014 were provided by Wang Huanbo, which provided ideas and methods. Zhou Long and Li Zhipeng collected experimental data in 2020, and Li Xin provided some water conservancy statistics in Xinjiang and data on water quality research of medium and long series of observation wells. All the authors reviewed the full text.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., Yang, P., Wang, H. et al. Study on the evolution of ecological environment and irrigation behavior since mulched drip irrigation in Yanqi basin, Xinjiang.

Sci Rep 15, 14778 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97991-4

-

Received: 05 September 2024

-

Accepted: 08 April 2025

-

Published: 28 April 2025

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97991-4

Keywords

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post