The Labor party has a legacy of action for the natural world. Now is the time for us to do

April 10, 2025

I’ve been wondering if I remember all my surprise encounters with animals in the wild.

I remember sitting totally still on a riverbank watching a platypus going about its business as the dusk descended, by a logging road on the boundary of Tasmania’s world heritage area. And a moose in the Yukon, blundering out of the scrub at full speed right in front of us, as terrified and surprised as we were. A huge thing, my vision filled with moose. It turned and kept bolting. And summer evenings camping on the Thredbo River where wombats make for strange silent sentinels, munching grass as humans rustle plastic and wrangle gas stoves, the fuss of cooking al fresco.

I remember them because they are moments of such stark joy. They are usually times of quiet in the soft evening light. Australian animals are generally both silent and reserved. And these moments are rare.

In the way of oil and water, my love of nature gets expressed by being deep in the political process, with all its banality and disregard. I sit in the heart of a major political party, the Labor party, trying to build the bridge from where we are to where we need to be. This may seem quixotic, but I prefer it to melancholy resignation.

Maybe politics can’t solve it. But it’s the best we’ve got.

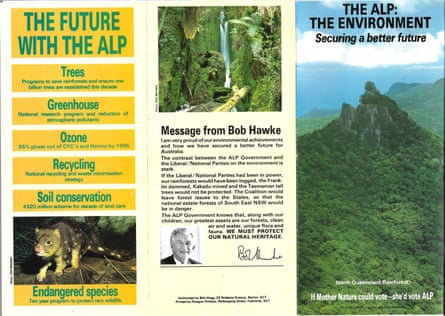

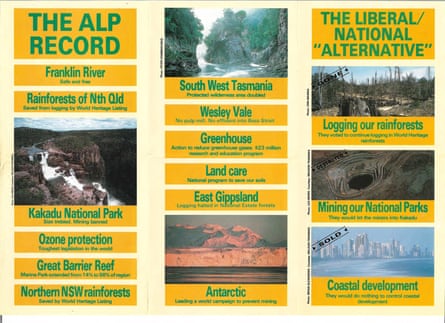

Labor has a deep legacy of action for the natural world. The Whitlam government brought environment into the heart of governing. In 1983, one of the first acts of the Bob Hawke government was to protect the Franklin River from a hydroelectric dam. Hawke ended rainforest logging, expanded Kakadu national park, led the international campaign to ban mining in Antarctica and began work on limiting greenhouse gases, appearing with his granddaughter in a 1988 documentary on climate change.

But the legacy is a 20th century one.

The past two decades have been dominated by responding to climate change. In the economy of politics, climate has taken all the space allotted to the environment. Finding the pathway to a safer climate hasn’t been easy, with the conservatives and vested interests weaponising it at every step, but Labor has stepped up in this term and a transition is under way. The gradual but certain collapse of the biosphere is threatening us just as comprehensively as a warming planet. And the political and policy response has been inadequate.

If re-elected, now is the time for Labor to do better. Governments can only do a certain number of things at once and we muffed the environmental law reform process this term. The power and ferocity of vested interests made clear how hard it is to shift the balance between commerce and the wild.

But in the last week, the prime minister has recommitted to the reform and the creation of an Environmental Protection Authority. Rewritten environment laws are the foundation on which we can turn it around. The central innovation is the creation of national standards, rules by which decisions are made about the environment. With proper application by an independent EPA there is a chance that we can begin to address our appalling record of stewardship.

But it will take more than laws. And more than money. It will only happen with strong and clear leadership. There’s a complex set of community capabilities and attitudes that need to underpin working out how to live well on our continent. And a tangled mess of overlapping responsibilities at different levels of government to address. We’ll also need incentives to make business consider its impacts on the uncosted natural capital it mines.

All this is politically possible because Australia is defined by its strange and magnificent environment. It shapes our culture, it sustains our leisure time, it marks who we are. As social researcher Rebecca Huntley says, “Twenty years of researching what Australians think is unique to our country, it’s not ‘mateship’ or a ‘love of sport’ but our unique natural places and iconic animals. We know they are the envy of the world, and what sets us apart.”

This fact is a potent political asset to be capitalised on. Addressing the Australian extinction crisis and the decline of our environment won’t become possible because the community decides it’s their number one concern, it will be because political leaders embrace it and argue the case, grounded in our national pride in our place.

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post