The ‘Most Important Case About the Internet Since the Internet was Invented’ Enters Its Fi

April 21, 2025

For many people, Google search is the default, as obvious and unremarkable as water is to fish. That could soon change.

In 2020, the U.S. Department of Justice and a group of states, later joined by California, accused Google of illegally stifling competition by paying to have its search engine as the default on web browsers and phones.

In the complaint, the DOJ argued, “Largely as a result of Google’s exclusionary agreements and anticompetitive conduct, Google in recent years has accounted for nearly 90 percent of all general-search-engine queries in the United States, and almost 95 percent of queries on mobile devices.” Google’s monopoly in general search services thus provided the company “extraordinary power as the gateway to the internet, which it uses to promote its own web content and increase its profits.”

Last summer, U.S. District Judge Amit Mehta agreed, ruling after a 10-week trial that “Google is a monopolist, and it has acted as one to maintain its monopoly.”

Now, during a remedies phase expected to stretch over several weeks, attorneys for the Justice Department and Google will present competing visions of how to remedy the company’s monopolistic behavior.

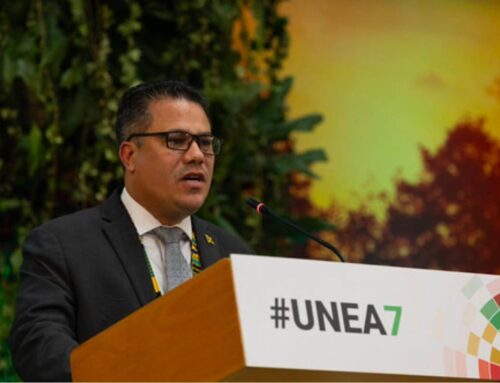

“The Google search case, in my opinion, is the most important case about the Internet since the Internet was invented,” said Doha Mekki, formerly a top antitrust official at the DOJ, and currently a senior fellow at UC Berkeley’s Center for Consumer Law and Economic Justice. “The idea that we have to trust all of our innovation and ingenuity to this small set of companies is actually deeply un-American.”

During her decade-long tenure at the Justice Department, Mekki had a front-row seat to a series of major antitrust cases the agency has pursued since the first Trump Administration, including cases against Google over its advertising technology and Facebook over its purchases of WhatsApp and Instagram.

Mekki argues this Google antitrust case comes at a pivotal moment when large tech companies are jostling for a lead position in the development of generative artificial intelligence. “AI has done nothing to disturb the Internet search monopoly. ChatGPT has not displaced Google search,” Mekki said.

The Silicon Valley giant has already said it will appeal. “The U.S. Department of Justice’s 2020 search distribution lawsuit is a backwards-looking case at a time of intense competition and unprecedented innovation. With new services like ChatGPT (and foreign competitors like DeepSeek) thriving, DOJ’s sweeping remedy proposals are both unnecessary and harmful,” Lee-Anne Mulholland, Google’s Vice President for Regulatory Affairs, wrote in a blog post.

In the company’s early days, Google’s search service was widely praised for its credibility. But over time, the company began to prioritize ad revenue, and its highly profitable advertising business has been powered by data harvested from user activity on Google Search and Chrome.

In the nearly three decades since Larry Page and Sergey Brin launched Google as a research project at Stanford University, the company has drawn criticism because of its practice of topping search results with paid product placements and even scam links. “We heard throughout the investigation and trial of this case that Internet search is not what it used to be, that the Google search page is now more littered with ads, and there’s more routing to Google’s products and services,” Mekki said.

The DOJ is seeking strong remedies to address Google’s unlawful monopoly in the online search market, including proposing that Google be required to sell its Chrome browser and barring Google from entering into agreements that set its search engine as the default on devices and browsers, such as those it has with Apple.

“It seems like a bad idea to have people paying tens of billions of dollars to buy placement of their search engines,” said Mark Lemley, who teaches intellectual property, antitrust and internet law at Stanford Law School. “We’d probably be better off in a world in which Apple couldn’t just auction off to the highest bidder what search engine you were going to use. But Apple’s not the defendant in this case. Google is.”

Lemley added that Judge Mehta’s challenge is to respond to a search market where there aren’t many viable alternatives to Google search.

Lemley argues that the court might consider giving consumers a choice screen from which they can select Google or one of its rivals, like Bing. “My guess is most people choose Google, and so it’s not obvious that the Google monopoly in search is much diminished if that happens, but at least we’re giving [consumers] an option up front.”

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post