There is no ‘optimal’ population size. It’s about long-term investment in human capital

September 21, 2025

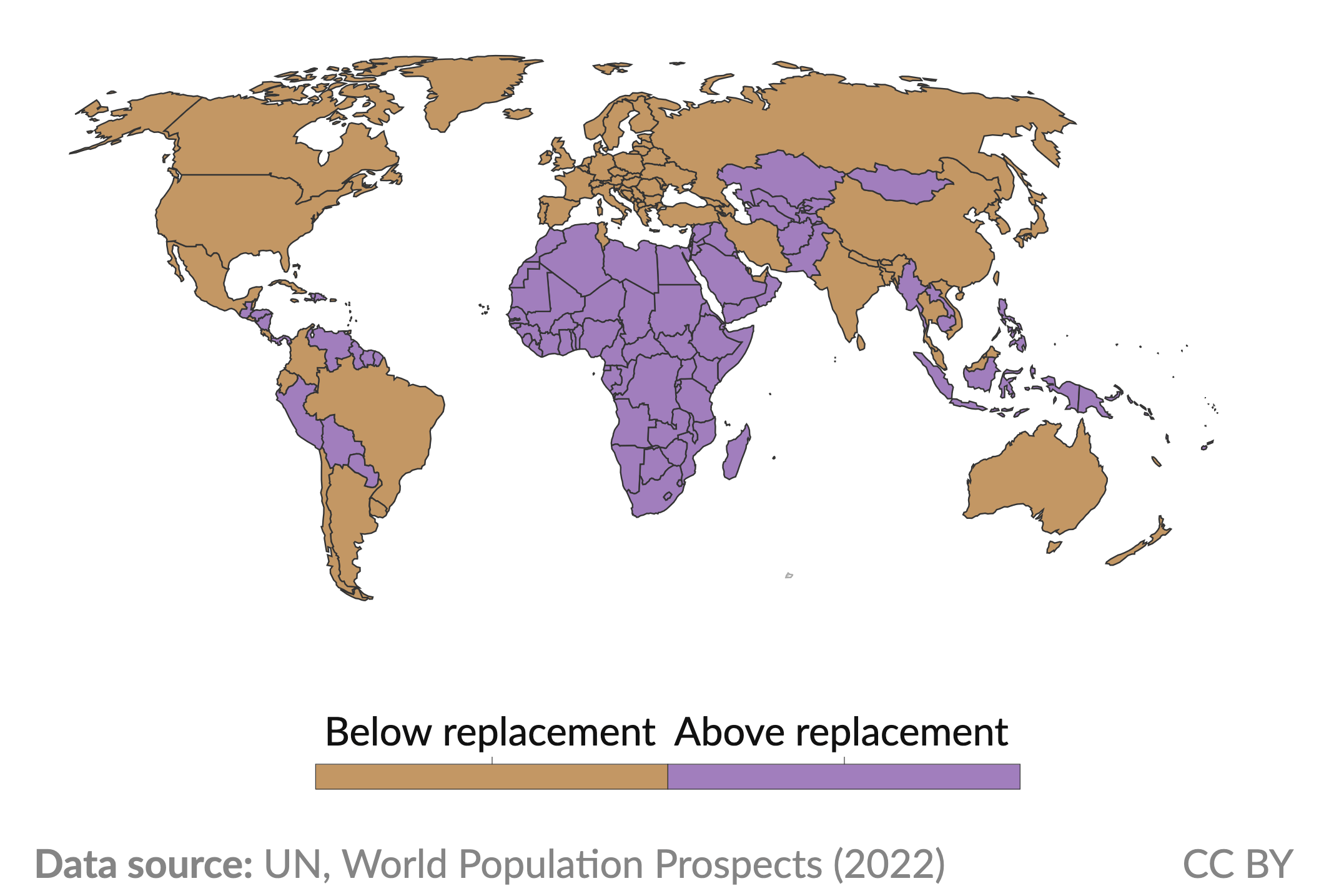

No longer confined to East Asia or Europe, low fertility has gone global. Most countries are now at or below the replacement level of 2.1 children per woman—including populous developing nations like India, Bangladesh, Brazil, Mexico, Türkiye, Indonesia, and the Philippines. As the popular narrative on “low-fertility countries” is slowly catching up, many are asking how far fertility will fall, and whether sustained rebounds are even possible.

Figure 1. Countries below and above replacement-level fertility

Image source: Our World in Data

Much of the anxiety about low fertility is fueled by an instinct that the population of a given country should be at a certain level, but when it comes to specifics, even a vague “ideal” is hard to pinpoint. Many of the world’s most livable, safe, and successful societies are not highly populated. The key question is whether a declining population confers a negative externality on society, and to what extent it can be either prevented or managed through adaptation.

The near-universal pattern of reduced fertility that comes with socio-economic development is well understood. But what will happen over the coming decades in today’s most developed countries—those at the forefront of declining fertility trends—is a subject of debate. In a recent global expert survey, most demographers predicted a slight decline within the 1-to-2-child range by 2050, either hovering around moderately low levels (around 1.6) or further slipping to “lowest-low” levels (1.3 and below), as seen most strikingly in South Korea.

Potential for rebounds

The 4+ sibling families, common only a few generations ago, are long gone in most of today’s wealthy countries—but the decline in intended fertility offers only a partial explanation for low fertility. Men and women in the U.S. and Europe report wanting somewhere between 2 and 2.3 children on average, notably above how many they have in the end. Such unrealized fertility desires are a clear precondition for any potential rebounds.

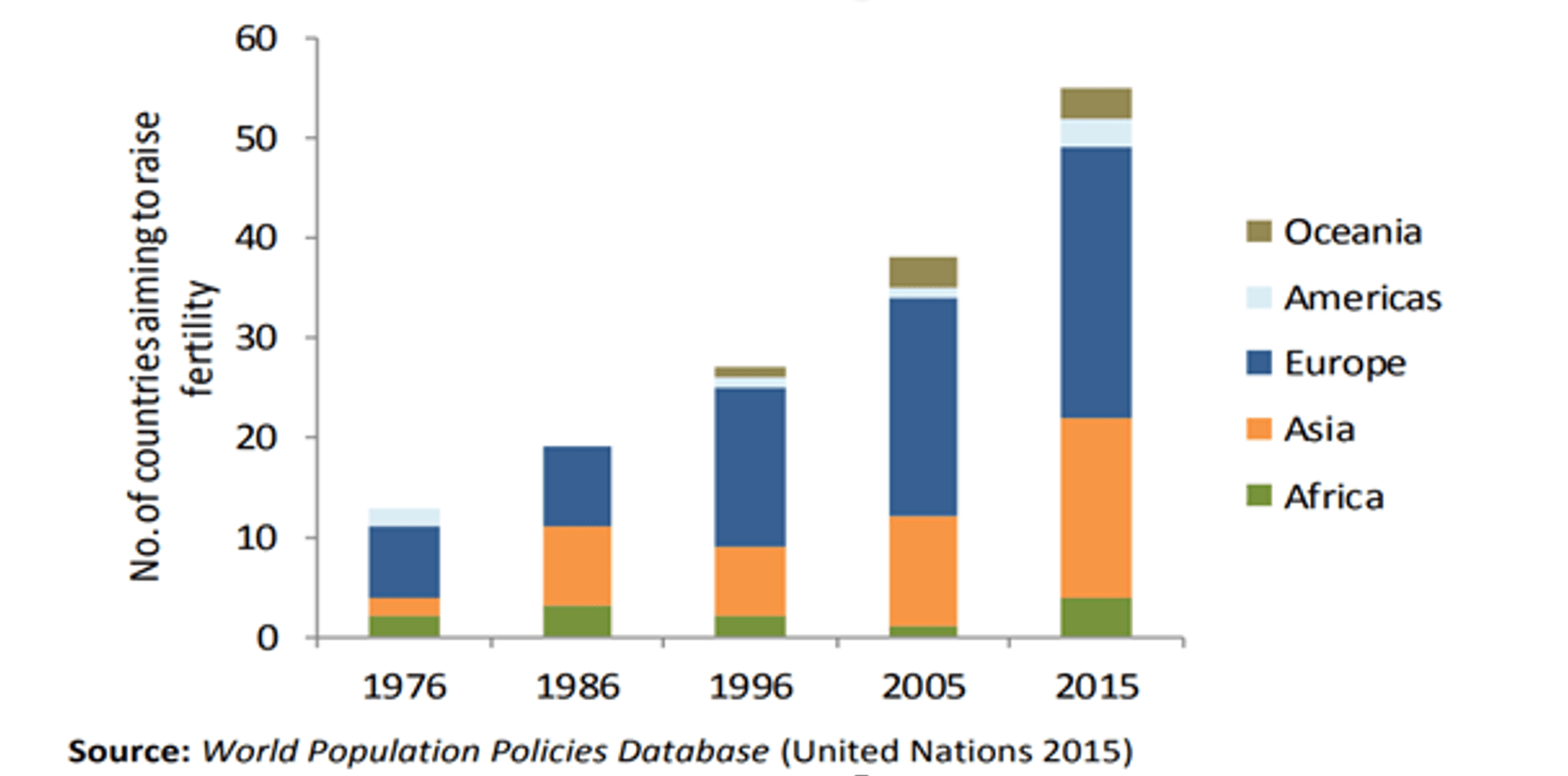

At least 55 governments have taken actions to lift fertility in recent times, but very few examples of sustained fertility recovery (particularly in wealthy nations) exist in modern history. The Nordic countries were long held up as fertility role models, offering flexibility and generous parental leave, but the formula seems to have lost some of its magic with recent drop-offs from near replacement level to below the OECD average.

Figure 2. Growth in the number of explicitly pro-natalist governments

Large-scale expansions of family benefits in Estonia, Germany, Japan, Russia, and other countries suggest that policy can make some difference. The immediate impacts (mostly influencing when couples decide to have children) can be to create mini baby booms, but the longer-term impacts on fertility are more modest (e.g., +0.10-0.25 children in Czechia and Russia).

Rapid fertility recoveries can occur after periods of uncertainty and economic disruption, as in Eastern Europe during the 1990s. Many countries in the region have seen rising fertility rates as couples who had postponed childbearing during the upheaval began having children—a reversion to the mean. A similar rebound will likely unfold in Ukraine, where the fertility rate has dropped below 1.0 in recent years.

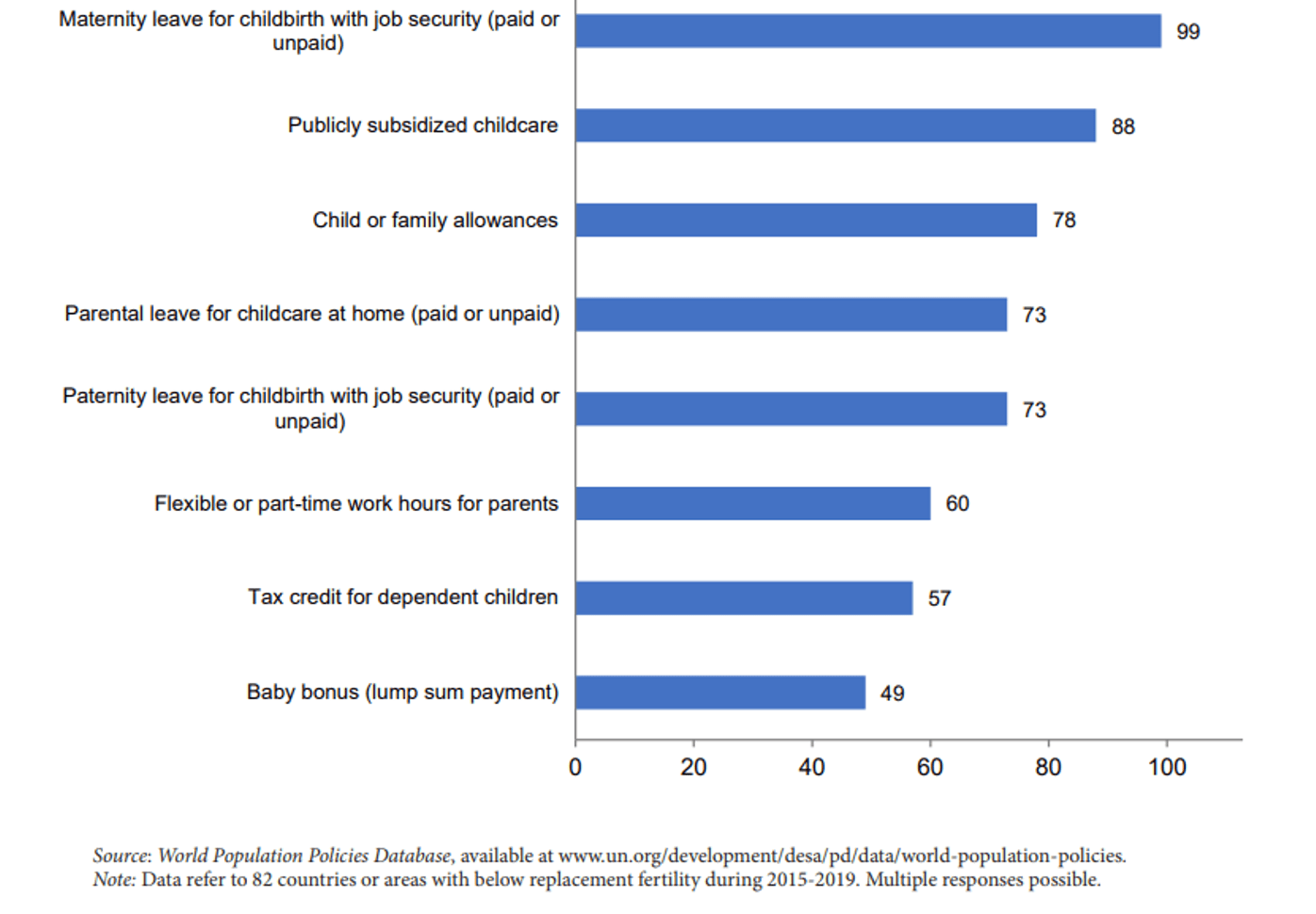

Of the popular measures pursued by governments, the most effective are focused on “structural” solutions, such as childcare access, rather than one-time baby bonuses. The quality of such services and their perceived stability are key ingredients in eliminating concerns among would-be parents.

Figure 3. Popular measures to improve work-life balance (% of low fertility countries)

Reckoning with the root causes

More than ever, parents’ time has become a limited resource amid the growing number of two-income households around the globe. Smaller extended families to rely upon, more elderly relatives to care for, and an increasingly planned, resource- and attention-intensive view of parenthood all make it more difficult to reconcile work with familial responsibilities.

Even securing a physical space for establishing a “nest” is out of reach for many potential parents. The average house price-to-income ratio has steadily climbed across the OECD, in many cases by more than 50% compared to when Generation Xers were young adults.

Less tangible, but perhaps most consequential, is individualism and the rhythm of modern life. More years are spent in extended adolescence, self-development, and education, with postponed entrance into the labor force and long-term partnerships. The OECD has seen an increase in the average age of marriage from 24.9 (1990) to 30.7 (2020) and a decline in marriage rates by 35% from 1990 to 2022. These changes have coincided with delaying the age at first childbirth and doubling rates of lifelong childlessness in many countries. Such norms continue to spread worldwide and are often quickly adopted by migrants within a generation of arriving in their host country.

Expectations about raising fertility should be realistic. Results are beyond the reach of any political cycle, and interventions are unlikely to fundamentally alter the multi-generational trends in motion. Decisions to start families remain inseparable from confidence in the future, community, cultural values, and overall economic conditions that go far beyond family policies in a narrow sense.

What is a meaningful demographic goal?

The feared consequences of a smaller and older population for the economy, labor force, or social systems are often oversimplified or presented as inevitable. In many countries, the GDP (both per capita and total) has increased alongside populations stabilizing or declining due to gains in productivity.[1] Looking ahead, the impact of today’s low fertility is inseparable from open questions about the state of technology and demand for labor in the coming decades.

Governments should not lose sight of a comprehensive human development policy. Ultimately, the goal should be building a resilient and cohesive society that cultivates its people—their abilities, health, and productivity. Human capital, not an arbitrary population size, is the decisive factor in determining whether a society can succeed. It offers a method for adaptation to low fertility, and potentially a path to higher fertility in the long run, both of which will be needed in any plausible future.

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post