Washington Post’s turnaround on its opinion pages is returning journalism to its partisan roots − but without the principles

March 17, 2025

Jeff Bezos, the world’s third-richest person and owner of The Washington Post, announced in February 2025 significant changes to the editorial pages of his Pulitzer-Prize winning newspaper.

The editorial section, also called the opinion section, is where editors and contributors with a deep and broad understanding of the latest news offer their analysis of the day’s issues. This content is distinct from the fact-based news reporting of the outlet’s everyday journalists.

Both kinds of content serve the public interest. Journalists report news to inform the public, while editors and opinion writers analyze and explain news, putting facts into a larger context to aid understanding.

At the Post, instead of news editors making independent decisions on what to write and the perspectives they should take, Bezos tweeted, “We are going to be writing every day in support and defense of two pillars: personal liberties and free markets. We’ll cover other topics too of course, but viewpoints opposing those pillars will be left to be published by others.”

Opinion and analysis in the Post was thus going to limit itself to one particular viewpoint.

As a journalism historian, I analyze how journalism has changed over time. Over the years, the purpose, practices and forms of journalism have evolved.

Bezos’ decision harks back to an earlier time when editors and owners were the same person, and newspapers offered a specific interpretation of the world, not just a neutral report.

Informed opinions and analysis

While editorial writers and opinion columnists offer their opinions, these views are still expected to be grounded in journalistic principles, building from verifiable facts and comprehensively considering context to offer well-reasoned analysis.

Many of today’s news editors and journalists stake their professional reputations on their obligation to truth, independent of special interests or particular ideologies. They pride themselves on reporting and explaining the news without fear or favor.

After Bezos’ announcement, editorial page editor and veteran journalist David Shipley resigned from his position. Shipley told his staff he was stepping down “after reflection on how I can best move forward in the profession that I love.”

Journalists and media critics from across the political spectrum read Bezos’ editorial policy change as going against the tradition of a paper that long prided itself on editorial independence in the name of public service. Historically, the newspaper’s opinion section offered a range of views on a variety of issues.

Limiting the newspaper’s opinion section to a single viewpoint, critics argue, doesn’t seem to align with the Post’s slogan, “Democracy Dies in Darkness,” as it stifles public discussion and purposefully turns off some of the lights.

Former Washington Post editor Marty Baron told the Guardian, “If you’re trying to advance the cause of democracy, then you allow for public debate, which is what democracy is all about.”

Putting all of this in historical context can help illuminate Bezos’ decision as well as the current state of American media.

The Print Collector/Print Collector/Getty Images

Opinionated early American journalism

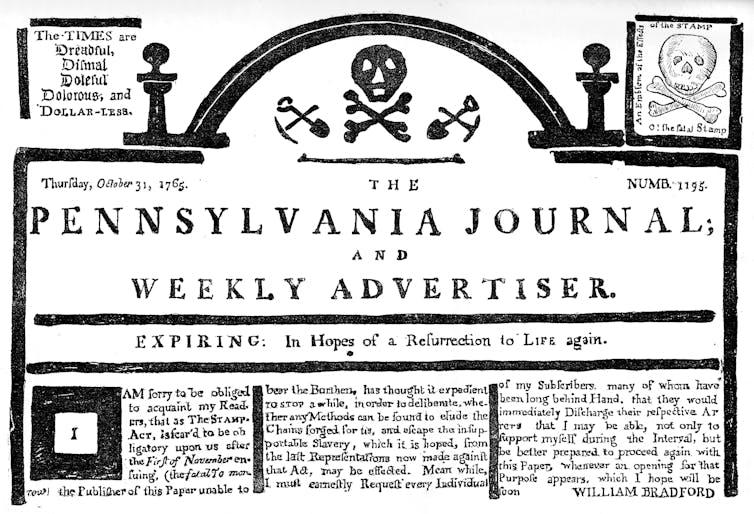

At the nation’s founding, the very first newspapers were highly partisan, supporting and receiving much of their funding from particular political parties and government subsidies. Newspapers were small operations where editors, owners, writers and typesetters were usually all the same person.

As the country and its political direction were just forming, these editor-owners felt a public obligation and duty to stake out a clear political position. There were no standards of journalistic neutrality; editor-owners framed news reports, wrote columns and published other people’s opinions based on their own particular viewpoints.

Editors wrote passionately, using language that suggested the fate of the nation was at stake. They were also principled and willing to criticize their own parties if they thought it warranted. And because they were transparent about their views, readers responded by gravitating to their preferred newspapers. Consequently, the number of newspapers in the U.S. increased from 35 in 1783 to 1,200 by 1833. Historians have thus argued that the early United States was a “nation of newspaper readers.”

Unlike modern notions of journalistic impartiality, if a newspaper didn’t support a political party or remained neutral, it was dismissed by readers as either lacking morals or being too stupid to form an opinion.

As newspapers of the early republic developed from reporting recycled news from other sources to guiding public discussion, the editorial thus emerged as a short opinion essay separate from reports on local speeches or foreign news.

Mandel Ngan/AFP via Getty Images

Fact-based journalism and informed analysis

For various reasons, the partisan press gave way to a journalism that attempted wider appeal. By 1900, many news outlets aimed for impartiality and neutrality.

By the 1920s, most journalists embraced the ideals of objectivity, the notion that journalists should only report facts.

Interestingly, this led to a growth in editorials, opinion columns and news analysis.

Opinion columns written by journalists provided interpretive frameworks for readers to understand the meaning of news events. One such journalist-commentator was Walter Lippmann (1889-1974), a political analyst who wrote a number of influential columns, including a piece infamously viewed as a catalyst for Japanese internment during World War II.

Such content provided journalists a means to show their independence from the powerful. Journalists could commit themselves to truth and verifiable facts while still asserting their independent role to contextualize news, explain its implications and guide the conversations necessary for democracy.

Research has shown that such opinion-based news content can influence what citizens and media outlets prioritize as important, as well as how policymakers approach certain issues.

Today, especially with the increase in partisan television, radio and internet outlets, there is no shortage of opinion-based news and analysis.

As long as people stay empathetic and open to others with different experiences, this is not inherently bad for democracy. Problems arise, however, when opinionated news outweighs fact-based reporting and people begin to mistrust all reporting they do not agree with, a psychological phenomenon known as confirmation bias.

In today’s digital world, everyone can broadcast or publish their opinion, whereas fact-based reporting takes time and resources. While news analysis and thoughtful opinion can generate important social conversations and help citizens understand news, too much opinion that isn’t grounded in facts can also lead to a general atmosphere of mistrust and suspicion. This spells trouble for the good-faith understanding, open dialogue and mutual trust so vital to democracy.

Profiting from polarization

Polling data suggests Americans are more divided than ever.

Perhaps Washington Post owner Bezos is simply responding to the public’s documented preference for partisanship over truth or to the profitability of partisan news.

But as a matter of context, there is a difference between the principled partisans of the early republic, the professional analysts of the 20th century, and an owner who demands his media outlet’s opinions should be limited to his preferences.

When he purchased The Washington Post in 2013, Bezos said the newspaper would not change and that “the paper’s duty will remain to its reader and not to the private interests of its owners.”

In this latest move, he has signaled that his private interest is a priority, at least for the editorial section. This limits the perspectives the Post-reading public can encounter and restricts the free marketplace of ideas. So when a Post journalist of 40 years wrote a column opposing Bezos’ editorial decision, her bosses refused to publish it.

Apparently, light criticism was not a “personal liberty” afforded a longtime employee. With her beloved employer not even willing to discuss the column – discussion being the cornerstone of deliberative democracy – the veteran journalist resigned.

In the current media environment, organizations and people who don’t participate in news production or share its values can purchase journalistic outlets and alter their standards and practices. As a result, principled journalists may decide to leave rather than compromise their mission of public service.

Ultimately, Bezos is being transparent. It is thus up to the American people to decide on the kind of journalism and pursuit of truth they desire. It’s worth noting that tens of thousands of canceled subscriptions have already begun to make that decision clear.

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post