What environmental history reveals about our current ‘planetary risk’

March 18, 2025

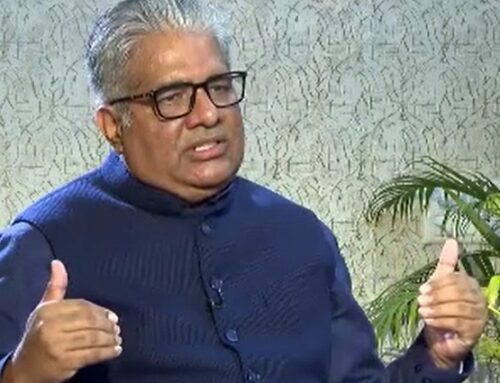

Recent and major shifts in international environmental policies and programs have precedent in history, but the scale and urgency of their potential impacts present a planetary risk that’s new, podcast guest Sunil Amrith says. A professor of history at Yale University, he joins the show to discuss the current political moment and draw comparisons across time.

“ When we look at examples from the past, [societies’ ecological impacts] have tended to be confined to a particular region, to those states, and perhaps to their neighbors. Because of where we are in terms of anthropogenic warming [and] planetary boundaries, I think the scale of any risk, the scale of any potential crossing over into irreversible thresholds, is going to have impact on a scale that I’m not sure historical precedents would give us much insight into,” he says.

Amrith is the author of The Burning Earth: A History, which examines the past 500 years of human history, colonization and empire, and the impact of these on ecological systems. In this conversation, he details some historical parallels that can be ascribed to the current global political moment — like the U.S. withdrawal from international agreements such as the Paris climate accord — and what history can teach us about these actions.

When asked what periods of history resulted in the greatest cooperation and peace, Amrith pointed to the post-World War II era, when “the U.N. and its agencies — a flawed but genuine attempt at global cooperation that came from that accompanied [by the] process of decolonization and political freedom coming to most parts of the world, allowing them for the first time to chart their own futures.”

Subscribe to or follow the Mongabay Newscast wherever you listen to podcasts, from Apple to Spotify, and you can also listen to all episodes here on the Mongabay website.

Banner Image: Rainstorm over Pillcopata in the Peruvian Amazon. Photo by Rhett Butler/Mongabay.

Mike DiGirolamo is a host & associate producer for Mongabay based in Sydney. He co-hosts and edits the Mongabay Newscast. Find him on LinkedIn and Bluesky.

Notice: Transcripts are machine and human generated and lightly edited for accuracy. They may contain errors.

Sunil Amrith: So, one of the things I’m curious about is what happens now when the U.S. has made quite clear that it has, the federal government at least has no interest in international agreements around environmental protection, around climate action. The question for me is, will other coalitions form? That circumvent the US. And even more interestingly, will they be able to actually find allies within the US as well? Because the federal government is not the only actor. I mean, at the state level, at the city level, there’s profound support for climate action and sustainability in the US. And I think there’s profound support amongst the younger generation for those things, which is precisely why the current administration is trying to censor school textbooks and going after universities. So I’m wondering about it. I think it’s too optimistic to call it a moment of opportunity, but if we bear in mind that the U. S. government has very often been an obstacle to international agreement around climate and sustainability, what happens if it’s actually now quite clear that the U. S. government’s not going to work with anyone on these things? What kinds of coalitions will form? What kinds of alliances? circumvent the US, but which perhaps are looking for allies at other levels of American government and society.

Mike DiGirolamo (narration): Welcome to the Mongabay Newscast. I’m your cohost, Mike DiGirolamo. Bring you weekly conversations with experts, authors, scientists, and activists working on the front lines of conservation, shining a light on some of the most pressing issues facing our planet and holding people in power to account. This podcast is edited on Gadigal land. Today on the Newscast, I speak with Sunil Amrith. A historian and professor of history at Yale University. He is the author of the recent book, The Burning Earth, A History, which examines how humans have shaped the planet over the past 500 years, examining histories of the environment, colonization, and empire. Today, he joins me to speak about some historical precedents to the current global political moment and the recent actions of the United States government. What actions we’ve seen before. And which ones we haven’t, and what lessons from history we can learn to teach us about this situation. Amrith offers a clear eyed perspective that fairly describes the severity and the planetary risk of continued environmental degradation at the hands of world leaders and nations. He also offers guidance on how to channel the anxiety one might feel, and reminders of when and how global cooperation and peace occur.

Mike: Sunil, thank you so much for joining us. Welcome to the Mongabay Newscast.

Sunil: Thanks for having me, Mike.

Mike: We’re going to talk today about what’s currently happening politically and how that compares to what has happened previously. But my first question for you is, what are some of the most significant environmental actions that have happened in this current government in the United States?

Sunil: I think abrupt and severe cuts to federal funding for science, including climate science, is perhaps top of the list. I think the attack on terms like environmental justice, which has been banned by the National Endowment for Humanities is another part of what’s happening. And I think the attack on the infrastructure of the federal government that has for decades enforced environmental regulations is going to have a, a long and lasting impact.

Mike: And there’s a lot of stuff we could talk about, probably too much for us to unpack in just this podcast episode, but historically speaking in the United States, have we been here before? Do you think

Sunil: In the United States, I’m not sure we’ve been here, but one of the things that strikes me is when I discuss with colleagues around the world, some of the current challenges I’ve been struck by how many of them express a sense of recognition, a sense that we’ve been here before. I think there’s nothing particularly new or unusual about capricious and in many ways, malign government. People around the world, unfortunately, have lived under such regimes for a long time. I suppose one of the things that’s different is just because of the wealth and the military power of the United States, the capacity of this administration to do harm is perhaps unprecedented.

Mike: Then let’s look to history because this is your area of expertise. Let’s look to history across the globe. What are some examples that stand out to you? How do environments or people tend to fare under regimes like this?

Sunil: I think in some ways what’s happening now is so multi faceted that I would tend to look to quite a range of different historical parallels for different aspects of what’s happening right now. one of the things that I think is most worrying about the current administration’s approaches, the sheer contempt for the rest of the world the disregard for international agreements, the language of, of dismissal when speaking about the United Nations, when speaking about the international architecture that was put up after the second world war, after the horrors of the second world war to try to forge global cooperation. And if we want precedence for that, I think, unfortunately, we’re going back to the 1930s when Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan did just that, tore up international agreements because of the perception that those international agreements were restraining their ability to exercise unilateral power. I think there are other precedents and parallels as well. I mean, in some ways, I’m also minded to think about the last period of European imperialism in Asia and Africa, where in a sense facing an endgame, what you see is colonial powers like the British and the Dutch sort of reinforcing repression, trying to censor articulations of, of anti colonial sentiment and In ways, I can see an element of that too in the particular hostility and aggression that the current administration has towards DEI, towards ideas like environmental justice.

Mike: And if we’re to look at, resource use because something that this administration has, has signaled is that it wants to use 280 million acres to exploit timber, for instance. That’s just one of those things. That’s a lot of land. That’s a lot of trees. Do you have any examples from history where countries have raised their forests in such a large amount all at once and what occurred?

Sunil: Absolutely. I mean, there, I think the parallel is really the 19th century. Including here in the United States, where you have this colossal scale of landscape transformation. And you see that also in places like Australia, you see it in Canada and the prairie, you see it in a colonized parts of Asia and Africa as well, where large scale deforestation for often for timber to use in railroad construction to use in naval construction really causes one of the most rapid periods of landscape transformation that I think we’ve ever seen. Many studies have shown that actually the scale of landscape transformation in the 19th century was in some ways more extensive than we have seen since then, partly because it was so rapid in the 19th century that many of these so called frontiers were effectively closing by the end of the century.

Mike: And What have been the impacts in those cases? What are some of the examples you can highlight where, Indigenous populations were impacted by the environmental policy of a nation seeking to exploit vast amounts of resources, kind of like this one is looking to do

Sunil: I think the example that comes most immediately to my mind, partly because of where I’ve done most of my research, is actually colonial India, where the British Empire, which in a sense was at the height of its power and its ambition, its demand on the world’s resources was at its peak in the second half of the 19th century. And the impact that that had on Adivasi communities in India, who. essentially were dispossessed. They were told that the forests are all state land for the state to exploit as it saw fit. That laid the groundwork for what have sometimes been century long studies struggles for justice on the part of Indigenous communities around India who still find the Post independence government of India and the forest department have a very repressive and proprietorial approach to land use, forest use, and these are, these are ongoing struggles, really.

Mike (narration): Hey listeners, thank you for tuning in to the Mongabay Newscast. The content you’re listening to right now is brought to you completely free due to the generosity of our supporters. If you want to help us continue to bring you independent non profit news and the audio editions of our work that you regularly listen to, please head to Mongabay.com and click on the donate button in the upper right corner of the landing page. Thank you very much. And back to our conversation with Sunil Amrith.

Mike: what are the things you’re most curious about examining as the months unfold here? What are you most interested in uncovering and seeing how things will play out?

Sunil: One of the things that occurs to me if we take a step back is I do think that the The sheer chaos and malevolence of the current administration is without precedent in the U. S. But what isn’t without precedent is the U. S. as an obstacle to climate and environmental progress. In fact, there’s a long history of that which goes back to the 1980s. Has tended to be stronger under Republican administrations, but not necessarily And, you know, I go back to 1992 and the Earth Summit when the first Bush administration, and that was when the infamous line, the American way of life is not up for negotiation. The U. S. essentially bullied countries, small countries, many of them Pacific Island states into not supporting Austrian and Dutch proposals for a binding treaty that way back in 1992. I mean, this would have been an opportunity for early and concerted climate action. And the U. S. essentially strong armed a number of countries into defeating that proposal. And we can see that at various points through the 1990s and 2000s. I mean, there’s a really interesting book by the journal Nathaniel by the journalist Nathaniel Ridge called Losing Earth about how the 1980s were the sort of turning point where until then, even in the U.S. there was quite a lot of bipartisan consensus around the need for environmental protection. I mean, let’s not forget it was under Nixon that the Clean Air Act is passed. I mean, so this is. New in some ways, the, the extreme polarization around environmental questions. So one of the things I’m curious about is what happens now when the U.S. has made quite clear that it has, the federal government at least has no interest in international agreements around environmental protection, around climate action. The question for me is, will other coalitions form? That circumvent the US. And even more interestingly, will they be able to actually find allies within the US as well? Because the federal government is not the only actor. I mean, at the state level, at the city level, there’s profound support for climate action and sustainability in the US. And I think there’s profound support amongst the younger generation for those things, which is precisely why the current administration is trying to censor school textbooks and going after universities. So I’m wondering about it. I think it’s too optimistic to call it a moment of opportunity, but if we bear in mind that the U. S. government has very often been an obstacle to international agreement around climate and sustainability, what happens if it’s actually now quite clear that the U. S. government’s not going to work with anyone on these things? What kinds of coalitions will form? What kinds of alliances? circumvent the US, but which perhaps are looking for allies at other levels of American government and society.

Mike: I don’t want to get too fatalistic with this next question, but if we look at history, there’s a number of examples where there have been civilizations that have like Kind of fallen off a cliff as it were in terms of like their resource use and their prosperity due to poor decisions from their leadership or their governments

Mike (narration): A very cautious note for my listeners here. I would strongly dissuade you from using the term civilizations, as I did here naively. While Sunil didn’t say this to me, in my research upon editing this episode, I found that historians generally see the term as problematic, it has been used to define certain groups either as civilized or uncivilized in history. It’s incumbent on me to make this clarification to you. ‘Societies’ or another term would have been better to use here

Mike: Is there such a is there such a cliff here do you think? What are some examples from history where? Perhaps like famous examples where civilizations fell off that environmental cliff and couldn’t retreat from. Are we in a similar position of risk here?

Sunil: I think we are, and I think what makes this different is that it’s planetary risk. I mean, when we look at examples from the past those civilizational collapses, if you want to use that term, have tended to be confined to a particular region to those states and perhaps to their neighbors. Because of where we are in terms of anthropogenic warming, in terms of where we are in terms of planetary boundaries I think the scale of any risk, the scale of any potential crossing over into sort of irreversible thresholds, is going to have impact on a scale that I’m not sure that historical precedents would give us much insight into. I mean, there are plenty of historical precedents. I mean, one which ended just appallingly badly, of course, is Imperial Japan. If you think about the driving force for Japan’s imperial expansion into Southeast Asia, the attack on, on, on Hawaii and Pearl Harbor so much of that was actually motivated by a sense of resource scarcity. It was Southeast Asia’s mineral resources that really attracted the attentions of Japanese military planners. And in my book, The Burning Earth, I talk about a map that’s produced just a year before the Second World War in the Pacific, in which Japanese military planners are literally mapped out Southeast Asia in terms of its mineral resources. And I mean, I can see that sort of mentality at work. even in the way in which Greenland is being talked about, even in the way in which colonial conquest is in a sense back on the agenda in a more explicit way than it’s been since the 1940s. And of course that project in Imperial Japan collapsed in disaster and Japanese people essentially paid the, the ultimate price for that disaster. One could look at post war Japan as a much more hopeful example of a society that’s rebuilt itself with much more attentiveness to to limits, to sustainability, and to, to international humility.

Mike: Obviously the administration is looking at placing these heavy tariffs on some of its closest trading partners and seemingly trying to onshore more production of things like, construction for housing or oil drilling for that matter. What are the impacts and global disruption this could have on resource use?

Sunil: I think, again, thinking about historical precedents, it does start to feel more like the 1920s and 30s, where the quest for self sufficiency is really what results from countries around the world opting out of a more Coordinated international trading system. each country starts to look to its own hinterland, often perhaps with more and more of a sense of needing to dominate that hinterland in order to secure the resources that can no longer be secured by global trade. Now, we’re on a podcast that’s talking primarily about environmental perspectives. It’s complicated when it comes to the environmental perspective on all of this, because as we know, unrestricted global trade is itself one of the things that has propelled the climate crisis since the 1980s and 1990s. I’m not sure that this particular approach is going to lessen resource use and make things any better, but there is an argument that people across the political spectrum have had about how much the current trading system incorporates emissions, for example, or thinks about externalities, as the economists call it, when it comes to the environmental consequences of some of the ways in which our economic arrangements play out.

Mike: I’m curious to know if you have any thoughts on Greenland because this is not first administration that has expressed interest in the world’s largest island. I believe Two previous U. S. Secretaries of State have both expressed interest in it, specifically in the 1800s and in the mid 20th century. Why would a foreign nation have interest in Greenland? What would be the purpose behind that, would you speculate?

Sunil: Very interesting piece just last week in Foreign Affairs magazine by the political scientist Michael Albertus, who’s the author of a really fascinating new book called Land Power. And Albertus argues that actually climate change has something to do with it, that Greenland is likely to be one of the places in the world where climate change actually makes things more habitable rather than less, as will be the case in many other parts of the world makes it more hospitable to agriculture. There is lots of speculation about the extent of mineral resources to be had. There’s the possibility of climate change also opening up a kind of northerly shipping routes. So then the sort of geopolitical strategic role of of Greenland. larger than it did. But in some ways, there’s always been a geopolitical mindset, which, as you say, you can see in the middle of the 20th century, you can see in the 19th century, that simply sees territory as a zero sum game that if we don’t control it, somebody else will. And so I think there’s also that much older mentality is still very much at play. And in some ways, I think it’s resurgent now.

Mike: Yeah, I mean, the, the obvious factor here is that the territory is already occupied and in control of, of Greenlanders. I mean, They’ve stated unequivocally that Greenland is not for sale. I suppose , we probably couldn’t speculate on how that would play out. But it seems like to me that there isn’t any legitimate or legal way to To occupy that land because it is already under the occupation of Greenlanders

Sunil: And, and there, I think we have a very, very long set of historical precedents. We can look to So many of the parts of the world that were occupied in the 19th century were already occupied. That is, that were occupied by Europeans and settlers in the 19th century were already occupied. And that’s where you have these elaborate legal doctrines of, of terra nullius and the idea that indigenous people are not using land productively and therefore they can be dispossessed. I mean, these are ideas that go back to the 17th century in North American history. And again, they haven’t really gone away.

Mike: Yeah, this is a quite I mean quite terrifying. I mean it’s really scary to think about what would occur. It seems like Sunil that there’s a lot of lessons from history that we could be learning or should be learning What would some of those lessons be, would you say? What are some of the most important lessons, do you think, that we should be learning right now, that perhaps maybe we aren’t?

Sunil: You know, I think the simplest lesson is that whether we’re interested in the state of the world’s environment or whether we’re interested in social progress and human well being, that it has tended to be in periods of peace and international cooperation that the greatest gains have been made. And I think that would be a lesson deeply worth heeding in our current moment of division and polarization and increasing conflict.

Mike: What were some of those periods?

Sunil: I think the period 1940s to the 1970s where two major things happened. One is the post second world war settlement, the UN and its agencies a flawed but genuine attempt at global cooperation that came from that. accompanied by the process of decolonization and political freedom coming to most parts of the world, allowing them for the first time to chart their own futures. I think the coming together of those two things in that middle or the sort of third, third, third quarter of the 20th century If you look at Thomas Piketty’s book on inequality, it is interesting that that is the moment of, of, of least inequality over more than a century of data that we have both within and across nations. I think a certain commitment to redistribution was more or less a subject of consensus. And it is really striking, particularly in relation to the US polarization of US politics today, that this was a moment where. Yeah, the Nixon administration is passing environmental legislation, and this is a moment in Britain when, you know, Margaret Thatcher’s government, which, while privatizing everything, is very early to take climate change seriously.

Mike: Yeah, that is a very a very interesting retrospective to look back and see that. So for those who are listening to this podcast, who may be experiencing A lot of anxiety, a lot of maybe eco anxiety about what’s happening now. What would you say to them to help them compartmentalize or unpack the current moment and what can be done about it?

Sunil: The first thing I’d say to them is, I feel it too, and very strongly. And that Is very, very challenging. I feel it when I teach my students. I feel it when I’m trying to write and think and I think compartmentalization, Mike is probably the right term for it. I do think that if we are thinking about the big picture of all of the risks all of the time, I think it could be very difficult to act. And I think that breaking things down into the local communities that we inhabit, whether these are intellectual communities, communities of ideas, or physical local communities, and think, it’s a luxury to say we’re just going to give up on this. Most people don’t have that luxury. And so I think thinking very concretely about solutions and actions that we can take in our lives, while at the same time, bearing in mind that yes, the odds are stacked against us in this particular moment. I feel this as a parent of young children and they talk about environmental concerns and questions all the time. And again, I don’t want to lie to them and tell them everything’s going to be fine. And at the same time, I see an inspiring energy and commitment in their generation, you know, under 12 years old to do things differently.

Mike: Sunil, is there anything that I haven’t mentioned in this conversation that you would like people to know about? Is there any lens or particular angle about this situation that we haven’t explored that you really think more people should be looking at?

Sunil: I do think we need to take a global perspective. In some ways, I think we need to dissenter the U. S. from our news feeds. What is happening in this country will have profound consequences for those of us who live here. But the U S is not, never has been the whole world. And I think it’s really important to hear voices from everywhere. Many of whom might have quite different perspectives on what we’re going through, or might at least have different reference points and different kind of chronologies with which to think about this current moment. And I think that can maybe open up our own imaginations to start to see things in a slightly different way.

Mike: Are there any nations or countries in particular that you’re looking at where you’re most curious to hear their perspective?

Sunil: I have long been very interested in the history of environmental activism in India, partly because it is so diverse. There’s not one environmentalism in India, but really a whole sort of collage of environmentalisms. And I continue to very attentively listen to ideas that are coming from there.

Another country, which I find absolutely fascinating because there’s so much creative thinking happening at the moment is Indonesia. The more time I spend in Indonesia, the more I think we have a lot to learn from activists there. Latin America for decades now, I think has kind of led the world in ways of thinking about environmental justice and environmental activism. And that’s a region of the world, which I know least well, and I’m most eager actually to learn from.

Mike: Sunil, if you wanted to direct listeners to learn more about your work, where should they go?

Sunil: If they’re interested I have a recent book that came out a few months ago called The Burning Earth, which is my perspective on really How did we get here to this point of planetary crisis? Going back quite deeply into history of the last 500 years or so to, to try to untangle the many paths that brought us here and hopefully to find some ways to do things differently.

Mike: Sunil Amrith, thank you so much for joining me today. It’s been a pleasure speaking with you.

Sunil: Thank you, Mike. It’s been my pleasure.

Mike (narration): If you want to check out The Burning Earth A History by Sunil Amrith, please see the links in the show notes. As always, if you’re enjoying the Mongabay Newscast or any of our podcast content and you want to help us out, we encourage you to spread the word about the work we’re doing by telling a friend and leaving a review on the platform you’re tuning in on. Word of Mouth is one of the best ways to help expand our reach. You can also support us by becoming a monthly sponsor via our Patreon page at patreon.com/Mongabay. Mongabay is a nonprofit news outlet. So when you pledge a dollar per month, it makes a big difference and it helps us offset production costs. So if you’re a fan of our audio reports from nature’s frontline, go to patreon.com/Mongabay to learn more and support the Mongabay Newscast. But you can also read our news and inspiration from Nature’s Frontline at Mongabay. com, or you can follow us on social media. Find Mongabay on LinkedIn at Mongabay News and on Instagram threads, Blue Sky, Mastodon, Facebook, and TikTok, where our handle is at Mongabay or on YouTube at Mongabay TV. Thanks as always for listening.

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post