Why Detroit’s energy grid still fails its poorest residents

May 14, 2025

Overview:

– In Detroit, houses of worship are caught in a funding freeze, unable to access $20 million in “community change grants” promised by the EPA for renewable energy projects.

– This setback, imposed by the Trump administration, highlights the ongoing challenges faced by poor communities of color in accessing cleaner, cheaper power.

As an ice storm slicked roads across eastern Michigan on Feb. 6, representatives from four houses of worship arrived at the offices of Democratic U.S. Sen. Gary Peters.

They wanted Peters to pressure the Trump administration to lift the funding freeze on $20 million in “community change grants” promised by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to houses of worship across Detroit to create community resilience hubs powered by renewable energy — offering shelter during weather emergencies and utility outages.

More than three months later, spring has come to Michigan — and yet the expected $2 million in funding for the St. Suzanne Cody Rouge Community Resource Center in Detroit remains on ice.

St. Suzanne Executive Director Steve Wasko says his organization — which provides meals, clothing, day care and other programs for residents of this predominantly Black neighborhood — has “received conflicting and sometimes contradictory communication about the grant.”

Wasko had been promised funding to install heat pumps, solar panels and a generator, among other upgrades. The retrofit would allow St. Suzanne to help more people while cutting an energy bill that can run up to $15,000 a month in the winter.

The funding freeze is just the latest setback for poor communities of color across the United States — including in Detroit, Los Angeles and Philadelphia — that are being left behind in the transition to cleaner, cheaper power.

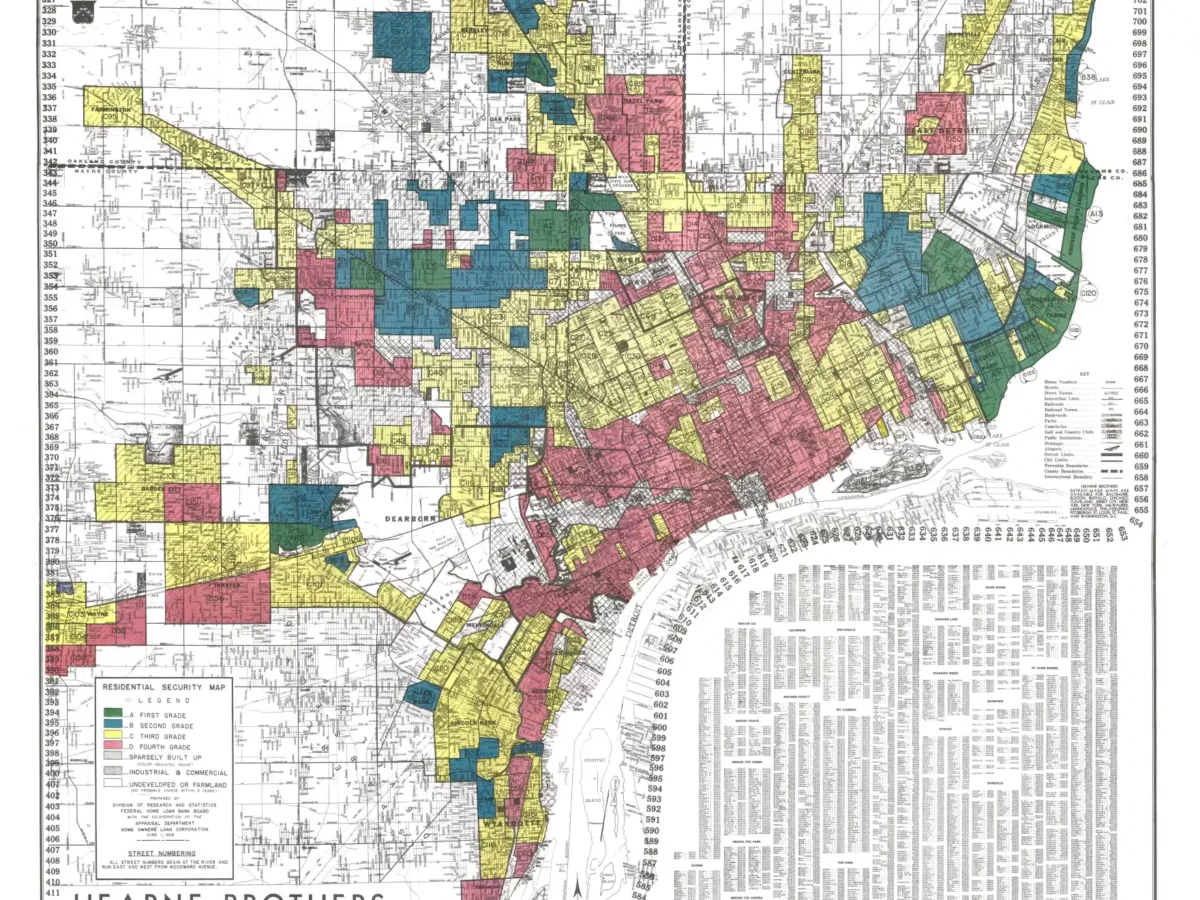

Neighborhoods like Cody Rouge suffer from underpowered electrical service, more frequent power outages and high energy bills — a legacy of the once-legal practice of redlining that robbed communities of color of financial and public services, Floodlight found.

In formerly redlined neighborhoods like Cody Rouge, shutoffs for non-payment are more likely. And poverty limits access to renewable energy: Aging roofs can’t support solar panels, outdated wiring can’t handle new heaters, and old electrical infrastructure struggles to accommodate electric vehicle charging and solar arrays.

“It’s now very clear that energy services, ranging from quality of service to price of service, are disproportionately poor if you are a minority, a woman or of low income,” said Daniel Kammen, professor of energy at the University of California-Berkeley.

learn more

Detroiters call on regulators to reject DTE’s rate hike, cite ‘utility redlining’

Juanita Gray has lived in her Detroit home for more than four decades. In recent years, she said she’s been paying higher electricity bills while service has deteriorated. She’s experienced several multi-day power outages that caused her to lose groceries. “Power goes out, stays out for a long time; when you try and call DTE…

Historical redlining impacts still felt nearly a century later

Last summer, the Department of Civil Rights conducted a health summit on the impacts of redlining in Michigan.

OPINION: How ghost streams and redlining’s legacy lead to unfairness in flood risk, in Detroit and elsewhere

Extreme weather events put pressure on cities like Detroit that have aging and undersized stormwater infrastructure, with low-income urban neighborhoods tending to suffer the most.

Little money, high bills

High energy costs are a burden across Detroit. A quarter of the metro area’s poorest households spend at least 15% of their income to power and heat their homes, according to a Floodlight analysis of data from the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy (ACEEE).

Across the United States, a quarter of all low-income households — roughly 23 million people — struggle to pay their energy bills. In most major U.S. cities including Detroit and Philadelphia, these one out-of-four low-income households pay 15% or more of their incomes on average on electricity, cooling and heat. In Los Angeles, this group pays just over 14% of their household income on utility bills.

These energy burdens have persisted for decades despite billions of dollars from federal and state governments subsidizing electricity bills in low-income communities. And now, Trump has gutted the Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program, which provides heating and cooling subsidies for 6 million U.S. households.

Other policy solutions face significant challenges. Energy subsidy programs suffer from low enrollment. Collective “community solar” efforts capable of bringing cheap renewable power to renters and the urban poor are stymied by utilities or not made available to folks with lower incomes.

During the Biden administration, tens of billions of dollars were allocated by Congress to help socially vulnerable groups participate in the energy transition. Trump froze much of that funding. Repeated court orders to resume the funding have been ignored or only partially honored.

The chaos has only deepened advocates’ concern that the disparities in America’s electric grid will persist — and perhaps even deepen.

“The current energy system has this imbalance, but if we don’t fix that, we’ll continue down that path, even as we transition to a cleaner, greener energy system,” said Tony Reames, professor of environmental justice at the University of Michigan.

Energy inequality across America

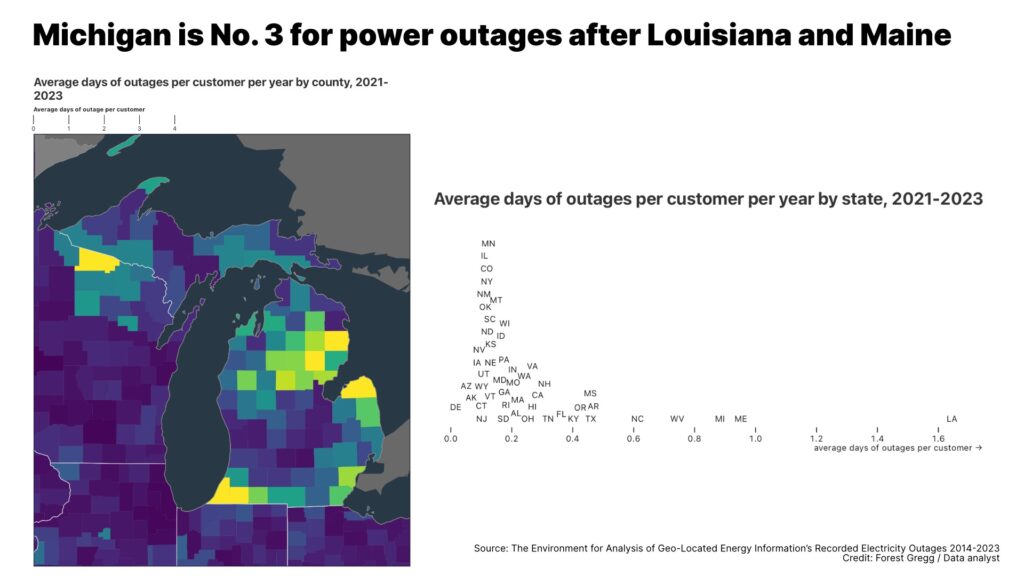

The inequalities in America’s energy system go beyond the cost of energy. In some states, minority communities are more likely to lose power. And in others, Black and brown residents are more likely to have their power shut off for nonpayment. Because of gaps in data collection, a clear national picture of energy inequality is difficult to see.

Across the United States, counties with high minority populations in Arkansas, Louisiana and Michigan are disproportionately prone to having long blackouts, according to a 2023 study in Nature Communications.

At least 3 million Americans face disconnection each year because they can’t afford utility bills, with Hispanic and Black households being four and three times more likely to be disconnected, respectively, according to the Energy Justice Lab, which tracks disconnections.

That number could be much higher, though, since only 28 states require their utilities to disclose disconnections, meaning no data is available for 44% of the country, according to Selah Goodson Bell, an energy justice campaigner with the Center for Biological Diversity.

The redlined grid

And in certain cities, the inequality extends to the very structure of the grid itself.

In Detroit and California, advocates and scientists have found that outdated utility infrastructure is concentrated in predominantly minority areas. This barrier may limit those neighborhoods’ ability to access renewable energy technologies such as rooftop solar, battery storage and electric-vehicle charging, which can lower energy costs.

When the lights flicker or go out in Detroit’s poorest neighborhoods, it’s often because of the electrical distribution grid.

Today in the Motor City, many low-income residents get their power through DTE Energy’s 4.8-kilovolt (kV) electric system, which struggles to keep up with the changing climate. Whiter, wealthier suburbs of Detroit are serviced by a more modern 13.8-kV grid. In rate cases, activists have accused DTE of prioritizing infrastructure upgrades in wealthier, whiter communities while leaving Black and brown neighborhoods with outdated and unreliable service.

Across the city, power lines and transformers are decades past their intended lifespan, leading to frequent outages and prolonged blackouts. Aging infrastructure, beset by summer heat waves and winter storms, led to almost 45% of customers suffering eight or more hours of service disruptions in 2023. A company spokesperson notes it improved reliability by 70% between 2023 and 2024.

“I know after three days without power, the strands of civilization get tested,” said Jeff Jones, Detroit resident and executive director of Hope Village Revitalization, a nonprofit community development corporation. “It can get really frightening.”

DTE says it has committed to improving the grid, citing a $1.2 billion investment in downtown Detroit’s infrastructure and a push to prioritize grid upgrades in vulnerable communities.

Lauren Sarnacki, a senior communications strategist at DTE, said the company also helped connect customers to nearly $144 million in energy assistance last year. And the utility runs a pilot program for households earning up to 200% of the federal poverty level, capping their energy costs at 6% of their income.

One Black church in Metro Detroit did not wait for the grid to improve. Last fall, New Mount Hermon Missionary Baptist Church weatherized, upgraded its heating system and installed solar panels and a battery with the assistance of the nonprofit Michigan Interfaith Power & Light and a state grant.

The solar array and battery give community members a chance to warm up or cool down in the building when the power is out in the neighborhood, said the church’s deacon, Wilson Moore.

“For the church itself, we’ve cut costs as far as energy consumption almost 40, 45% — and that’s without even solar panels up,” he said.

The Los Angeles Department of Water and Power also operates a 4.8-kV distribution grid in certain neighborhoods, including in Boyle Heights, a predominantly hispanic East LA enclave that was once redlined and has now begun to gentrify.

There, aging transformers and outdated service lines mean that businesses installing EV fast-charging stations or anyone trying to plug in a large solar array may have to pay for grid upgrades, according to an NREL study.

“Grid limitations could limit the success of other clean energy equity programs,” the study concluded.

The shadow of redlining remains

Old roofs also are a major barrier to rooftop solar adoption across Los Angeles, according to Alex Turek, deputy director at GRID Alternatives Greater Los Angeles, a nonprofit that deploys renewable energy in low-income neighborhoods.

“I think 70% or more of our folks who we build trust with, who are ready to move forward, can’t then adopt solar because their roofs are old and can’t support the weight,” Turek said.

Floodlight spoke to 18 organizations attempting to deploy renewable energy in low-income communities across the country. All of them said that poor housing stock, which is often concentrated in formerly redlined neighborhoods, was a major barrier to their work.

For renters and apartment dwellers, community solar may be a solution by allowing low-income residents “a way of dividing up an array and sharing it among multiple people,” said Alan Drew, a regional organizer with the Climate Witness project, a faith-based climate nonprofit.

Programs in 24 states and Washington, D.C., support this form of collective solar energy, which generates enough energy to power more than a million homes, according to a yearly survey from the NREL. Most of the locations also offer financial assistance for low-income households to access this form of energy, according to the NREL study.

However, in Michigan and Pennsylvania, investor-owned utilities have stymied the adoption of community solar. California has 13 solar projects built on the community solar model, but only one — the Anza community solar project in Santa Rosa — is dedicated to low- and medium income customers.

The state does have the Solar on Multifamily Housing (SOMAH) program that has subsidized over 700 solar arrays on multifamily affordable housing units, bringing costs down for some 50,000 apartments. The program makes sure that the cost savings don’t just go to the landlord.

“The smart policy design feature of the SOMAH program is that at least 50% of the system has to benefit the tenants,” said Turek, of GRID Alternatives.

Solar helps cool city

On sweltering afternoons in Hunting Park, the heat rises in waves from the asphalt, baking the brick rowhouses. The Philadelphia neighborhood’s sparse tree cover offers little relief — only 9% of it is shaded, compared to 20% of the city overall.

The effect is brutal. With much of its land covered in concrete, brick and blacktop, temperatures in Hunting Park can soar as much as 22 degrees higher than in other parts of Philadelphia. That difference translates directly into higher electricity bills as residents struggle to cool aging homes that were never built for such extreme heat.

Charles Lanier, executive director of the Hunting Park Community Revitalization Corp., said some residents pay as much as 40% of their incomes to heat and cool their homes.

“I’ve seen bills as high as $5,000,” Lanier said. “It’s a problem across the board in marginalized communities here in the city of Philadelphia.”

In Hunting Park and in low-income neighborhoods across the City of Brotherly Love, the Philadelphia Energy Authority has braided together several grant and funding streams to repair, weatherize, electrify and add solar power to some 200 low-income homes across the city in a state where community solar is not allowed.

The agency also runs Solarize Philly, a program that has helped install solar panels on some 3,300 homes, including low—to moderate-income households.

“We think low-income solar is the best way to create long-term affordable housing,” said Emily Shapira, CEO of Philadelphia’s Energy Authority.

Lanier has seen the value of solar firsthand.

“Here at our office, we have installed rooftop solar panels. Our electric bill has gone from $100,” he added, “to almost zero.”

By Mario Alejandro Ariza, an investigative reporter and a Dominican immigrant. His byline has appeared in the South Florida Sun Sentinel, The New Republic and NPR.

Planet Detroit reporter Ethan Bakuli contributed to this story.

This story was supported by a grant from the Fund for Environmental Journalism.

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post